GUEST CURATOR: Ethan Sawyer

What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“All Sorts of Doe and Buck-Skin Breeches.”

This advertisement announced the arrival of John Saltmarsh, a “LEATHER BREECHES MAKER” from London. He offered to make breeches for anyone who needed them in Norwich, Connecticut. He uses both doe and buckskin and made them fit properly. He also promised they would fit well, offering to “make them fit properly, or demand nothing for his trouble.” This sounds confusing, but it was the equivalent of modern lawyers only asking for a payment if they win. Saltmarsh was that confident in his ability to make new breeches or alterations that pleased his customers.

I was not sure what “breeches” were when I first read this advertisement. From an interview with historian Kate Haulman in Vox, I learned that breeches are a kind of pants made distinctive through the wrappings that tighten them just below the knees. Some had buttons or buckles, but for a cheaper option some just had simple ties to hold them in place. They were fashionable, which was one reason Saltmarsh said that he was “from London,” but that was not the only way he tried to convince customers to buy breeches from him. He also focused on service, promising the work to be done with “one Day’s Notice” or else he will compensate the customer for the inconvenience. He even said, “he will pay for their trouble of coming after them.” Overall, Saltmarsh ran an honest business. He focused on not only making a good product that fits the needs of each customer, but also on a timetable that works for them.

**********

ADDITIONAL COMMENTARY: Carl Robert Keyes

One of my favorite parts of having students in my upper-level early American history courses serve as guest curators for the Adverts 250 Project is observing their sense of wonder and discovery as they encounter everyday life in the eighteenth century for the first time. That starts with each student compiling an archive that consists of one week of newspapers published during the era of the American Revolution. Those newspapers look familiar, but they also have significant difference compared to modern newspapers … and not just the long “s” that looks so strange to novice researchers. The purposes of some advertisements surprise them, such as what are today known as “runaway wife” advertisements in which husbands made public proclamations that they would not pay any expenses incurred by the unruly women who abandoned their household responsibilities (and that gives us a chance to discuss both coverture and the perspectives of the wives who did not have ready access to the public prints). Students also encounter consumer goods commonly advertised in early America that are not familiar to them, such as andirons and “AMERICAN CAKE-INK.” Breeches also fall in that category. Ethan was not the only student enrolled in my senior seminar in Fall 2025 who included an entry on breeches in the advertising portfolio he created throughout the semester.

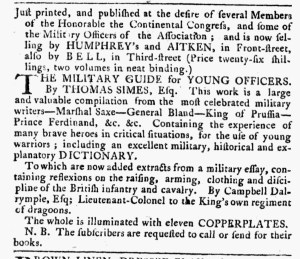

In addition to seeing fresh perspectives on consumer goods, I am always interested to see which advertisements draw the attention of my students because they usually select different advertisements to examine as guest curators than I would if I produced that entry of the Adverts 250 Project on my own. I would have skipped over “JOHN SALTMARSH, LEATHER BREECHES MAKER, FROM LONDON,” in favor of the two advertisements for Thomas Paine’s Common Sense that appeared in the March 4, 1776, edition of the Norwich Packet, advertisements even more notable because the printers also included “EXTRACTS FROM A PAMPHLET ENTITLED, COMMON SENSE.” Perhaps they previewed the pamphlet for the edification of their readers, though they likely also hoped to incite greater demand for sales of the pamphlet at their printing office. This helps make a point that I underscore in all my courses: the stories that historians tell about the past depend on the sources they consult and, among those, which they choose to examine in greater detail. Ethan and I both chose advertisements that illuminate the past, though different advertisements engaged our curiosity. Elsewhere in his advertising portfolio, Ethan examined other advertisements from other newspapers. Considered together, his advertisements looked at many aspects of consumer culture, commerce, politics, and everyday life during the first year of the Revolutionary War. They included an advertisement for a riding manual “for gentlemen of every rank and profession,” an advertisement for pig iron, an advertisement for an assortment of books and pamphlets for supporters of the American cause, … and an advertisement for a local edition of Common Sense that appeared in the March 1 edition of the Connecticut Gazette. When we perused that newspaper, Ethan and I selected the same advertisement!