What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“AN AMERICAN EDITION.”

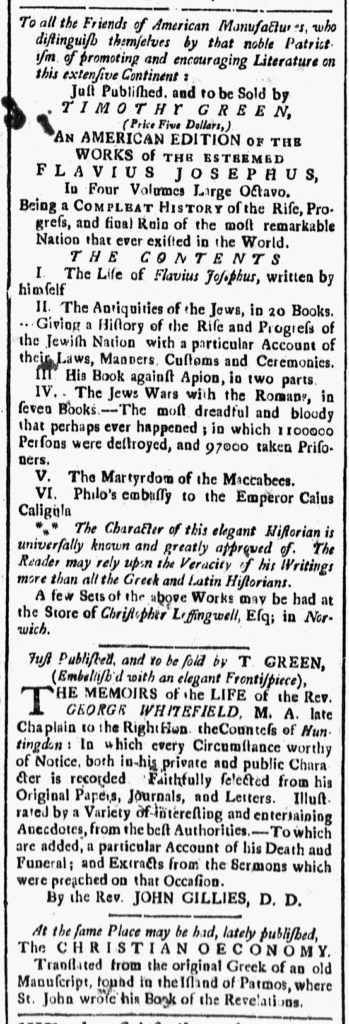

Calls to “Buy American” during the imperial crisis and the Revolutionary War extended to advertisements for books. In the October 27, 1775, edition of the Connecticut Gazette, Timothy Green, the printer, promoted three works published in the colonies and available at his printing office in New London. He addressed the advertisement to “all the Friends of American Manufactures, who distinguish themselves by that noble Patriotism of promoting and encouraging Literature on this extensive Continent.”

Those books included the “MEMOIRS of the LIFE of the Rev. GEORGE WHITEFIELD,” one of the most famous ministers of the era. When he died in Newburyport, Massachusetts, on September 30, 1770, news spread throughout the colonies as widely and as quickly as news about the Boston Massacre earlier that year. John Gillies compiled the memoir from Whitefield’s “Original Papers, Journals, and Letters” and added “a particular Account of his Death and Funeral; and Extracts from the Sermons which were preached on that Occasion.” They originally appeared in a London edition published in 1772, but Green most likely sold an American edition printed by Robert Hodge and Frederick Shober in New York in 1774.

For another of the books, The Works of Flavius Josephus in four volumes, Green triumphantly proclaimed that it was an “AMERICAN EDITION.” Earlier in the eighteenth century, American printers sometimes put a London imprint on the title page of books they printed in the colonies, believing that customers preferred imported works. Mitch Fraas, curator at the Kislak Center for Special Collections, Rare Books, and Manuscripts at the University of Pennsylvania, notes the prevalence of “books printed in America … bearing the false imprint of European cities.” That seems to have been the case with two 1773 editions of The Works of Flavius Josephus with a New York imprint yet “Probably printed in Glasgow,” according to the entries in the American Antiquarian Society’s catalog. Yet colonizers had access to an authentic American edition … and Hodge and Shober had been involved in the production, just as they had printed an edition of The Christian Oeconomy, the final book in Green’s advertisement, in 1773.

Rather than looking to London to provide them with books, some printers and booksellers embraced American editions and encouraged prospective customers to do the same. Green framed doing so as the patriotic duty of “Friends of American Manufactures” who supported the American cause and participated in the Continental Association, a nonimportation agreement enacted throughout the colonies in response to the Coercive Acts. Readers could do their part to defend American liberties through the choices they made in the marketplace, including purchasing an “AMERICAN EDITION” when they went to the bookstore.