What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Manufactures of all kinds in America tend to promote the welfare of it.”

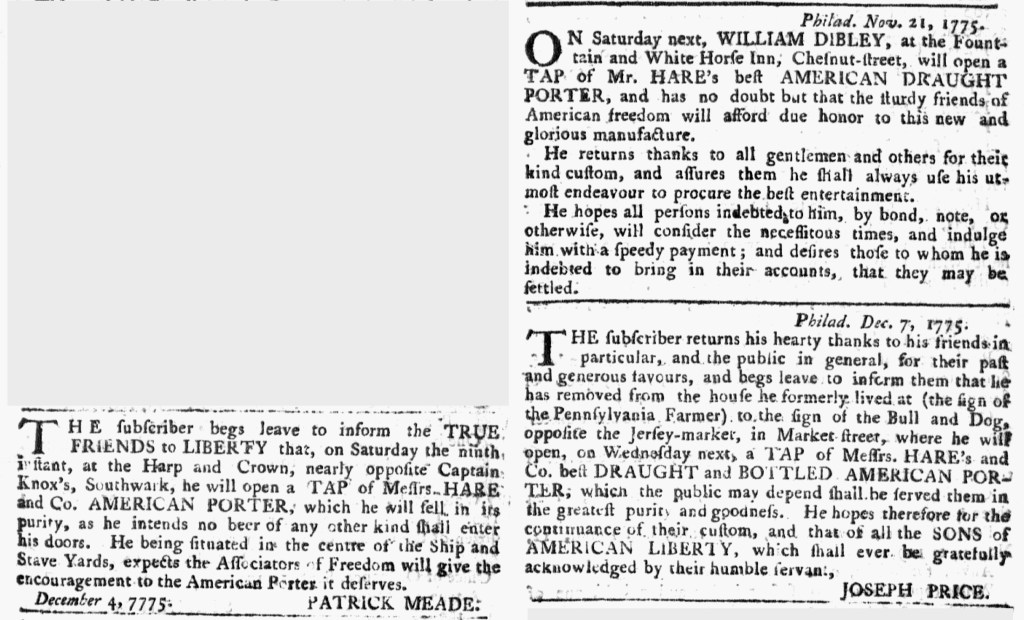

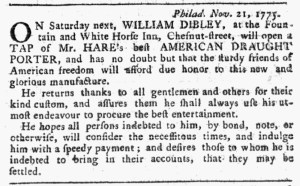

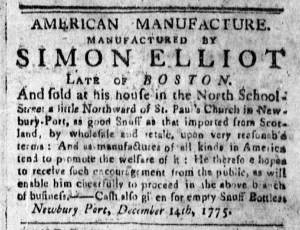

In December 1775, Simon Elliott took to the pages of the Essex Journal, printed in Newburyport, Massachusetts, to promote the snuff that he made in that town. He published his advertisement as the siege of Boston continued, much of the copy testifying to the imperial crisis that had become a war with the skirmishes at Lexington and Concord the previous April.

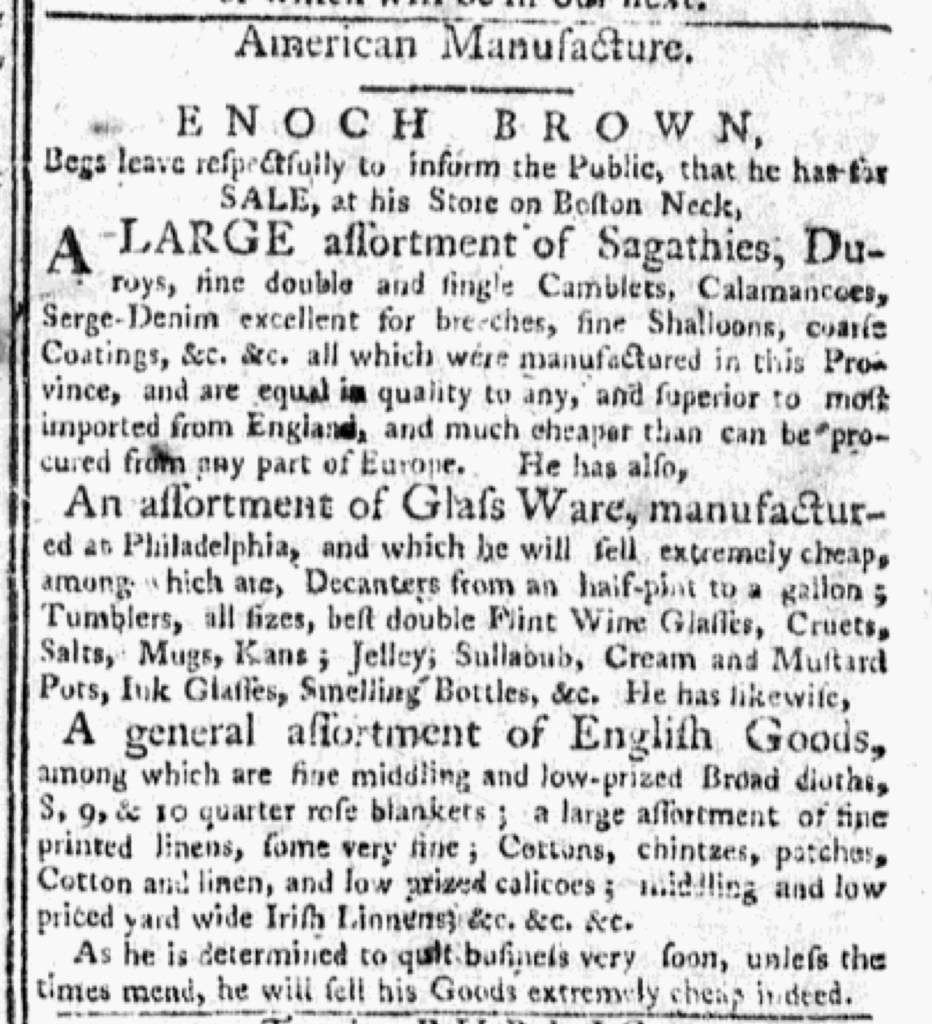

The advertisement featured an elaborate headline. Indeed, it had a primary headline and a secondary headline, like many other newspaper advertisements. Elliot’s name, centered and all in capital letters of a larger font than anything else in that issue of the Essex Journal except the name of the newspaper in the masthead, demanded attention. It was the second line of three, the other two also centered and in capital letters but smaller fonts: “MANUFACTURED BY / SIMON ELLIOT / LATE OF BOSTON.” A secondary headline, “AMERICAN MANUFACTURE,” appeared above the headline that made Elliot’s name so prominent.

Like so many other artisans when they moved to new towns and introduced themselves to prospective customers, Elliot mentioned his origins. Usually, “OF BOSTON” sufficed, but in this instance “LATE OF BOSTON” likely indicated that he had been displaced from that city recently. Many residents chose to leave following the outbreak of hostilities. In the early days of the siege of Boston, the Sons of Liberty and General Gage negotiated an exchange that allowed Loyalists to enter and others to depart. In the following months, newspapers throughout New England carried advertisements by entrepreneurs “from Boston,” a diaspora of refugees displaced at the beginning of the Revolutionary War.

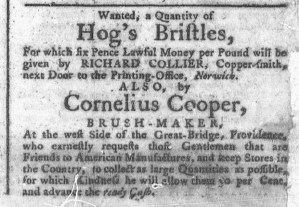

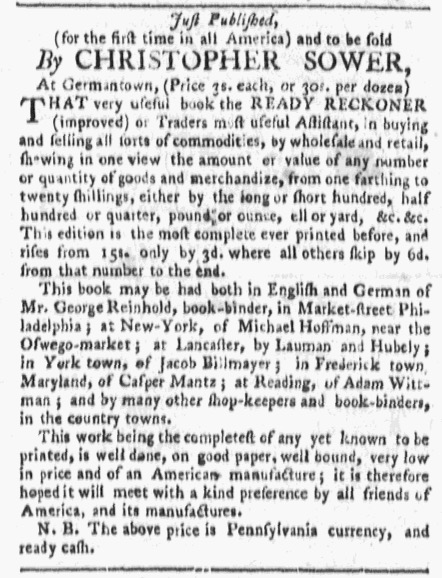

In addition to signaling the hardships he recently faced, Elliot also promoted the quality of the snuff that he made in Newburyport, asserting it was “as good Snuff as that imported from Scotland.” That was no small claim since tobacco processed into snuff in Scotland had a superior reputation at the time. Yet Elliot had more to say about his “AMERICAN MANUFACTURE” and why consumers should favor it over others. Echoing the Continental Association, a nonimportation agreement devised by the First Continental Congress, and popular discourses of the last decade, Elliot declared that “as manufactures of all kinds in America tend to promote the welfare of it: He therefore hopes to receive such encouragement from the public” to support his new enterprise. Supporters of the American cause, he suggested, had a civic duty to purchase the snuff that he made in Newburyport as well as support other entrepreneurs who produced domestic manufactures.