What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“He is determined to be undersold by none.”

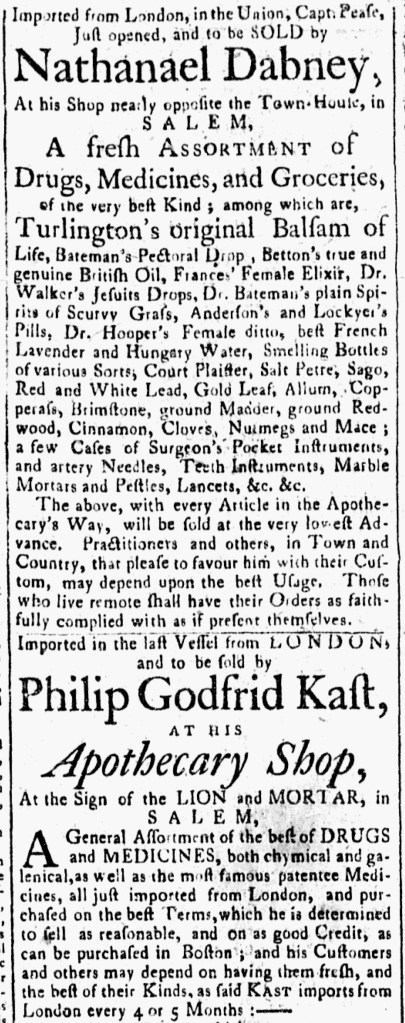

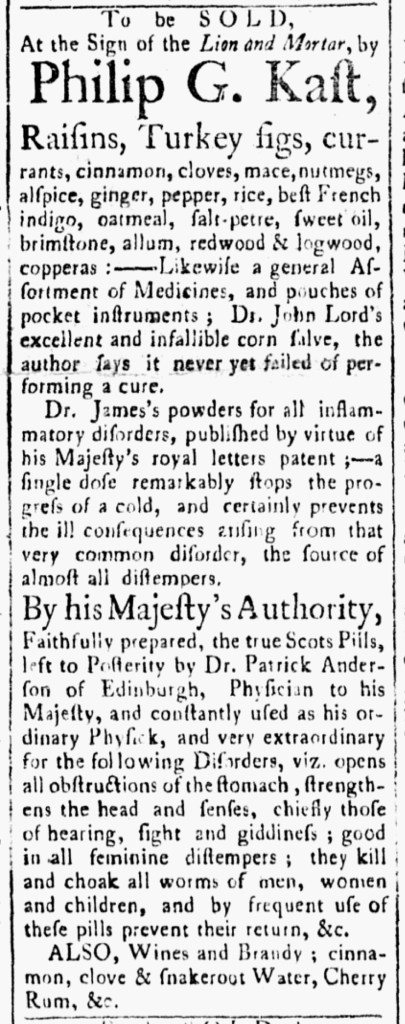

Philip Godfrid Kast, an apothecary in Salem, regularly placed advertisements in the Essex Gazette in the early 1770s. He also distributed an engraved trade card that included a depiction of the “Sign of the Lyon & Mortar” that marked his location. Kast resorted to a variety of marketing appeals in his efforts to convince consumers to give him their business rather than acquire medicines from his competitors.

In an advertisement that ran on June 9, 1772, Kast declared that he “is determined to be undersold by none.” Purveyors of all sorts of goods frequently promised low prices for their wares, some making similar claims that prospective customers would not find better bargains than they offered. Kast explained why he was so confident that he could match and beat the prices charged by other apothecaries as well as merchants and shopkeepers who imported and sold various patent medicines. He stated that he “has a Brother who resides in London, and purchases his Drugs at the cheapest Rate for Cash.” His competitors may have acquired their medicines through middlemen and marked up their prices accordingly, but Kast had a direct connection that allowed him to set the best rates. The apothecary presented this as a benefit to all of his customers, but he made a special appeal to “Gentlemen Practitioners in Physick” who were most likely to buy in volume. That meant greater savings for them as well as greater revenues for Kast.

Yet he did not expect low prices alone would bring customers to his shop. He also testified to the quality of his medicines and provided a guarantee, proclaiming that they were “warranted to be genuine, and the best of their Kinds.” Furthermore, his new inventory was “fresh,” having been imported from London” via a vessel that “arrived at Boston last Week.” Kast assured prospective customers that he did not peddle remedies that had lingered on the shelves for months. He anticipated that a combination of low prices and promises about quality would convince consumers to visit the Lion and Mortar when they needed medicines.