What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“At the Sign of the Lion and Mortar.”

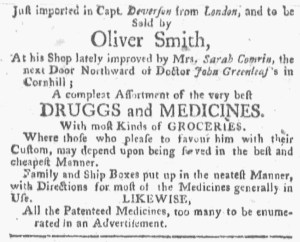

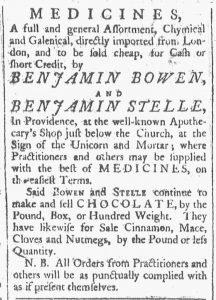

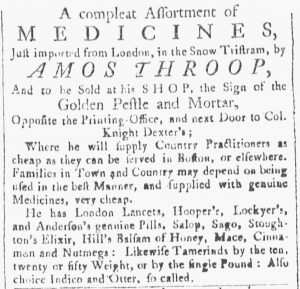

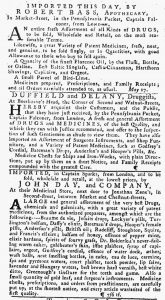

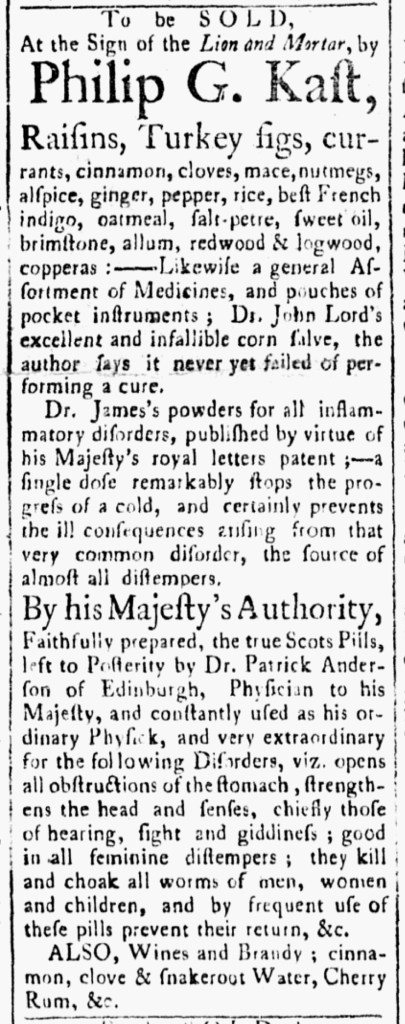

In the fall of 1770, Philip Godfrid Kast, an apothecary, placed an advertisement in the Essex Gazette to inform potential customers that he carried “a general Assortment of Medicines” at his shop “At the Sign of the Lion and Mortar” in Salem, Massachusetts. Purveyors of goods and services frequently included shop signs in their newspaper advertisements in the eighteenth century, usually naming the signs that marked their own location but sometimes providing directions in relation to nearby signs. On occasion, they included woodcuts that depicted shop signs, but few went to the added expense. Eighteenth-century newspaper advertisements provide an extensive catalog of shop signs that colonists encountered as they traversed city streets in early America, yet few of those signs survive today.

Kast did not incorporate an image of the Sign of the Lion and Mortar into his newspaper advertisements in the fall of 1770, but four years later he distributed a trade card with a striking image of an ornate column supporting a sign that depicted a lion working a mortar and pestle. Even if the signpost was exaggerated, the image of the sign itself likely replicated the one that marked Kast’s shop. Nathaniel Hurd’s copperplate engraving for the trade card captured more detail than would have been possible in a woodcut for a newspaper advertisement. Absent the actual sign, the engraved image on Kast’s trade card provided the next best possible option in terms of preserving the Sign of the Lion and Mortar given the technologies available in the late eighteenth century. Trade cards, however, were much more ephemeral than newspapers and the advertisements they contained. That an image of the Sign of the Lion and Mortar survives today is due to a combination of luck, foresight (or accident) on the part of Kast or an eighteenth-century consumer who did not discard the trade card, and the efforts of generations of collectors, librarians, catalogers, conservators, and other public historians. Compared to woodcuts depicting shop signs in newspaper advertisements, trade cards like those distributed by Kast even more accurately captured the elaborate details. Those shop signs contributed to a rich visual landscape of marketing in early America.