What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“JOURNAL of the whole proceedings of the continental congress.”

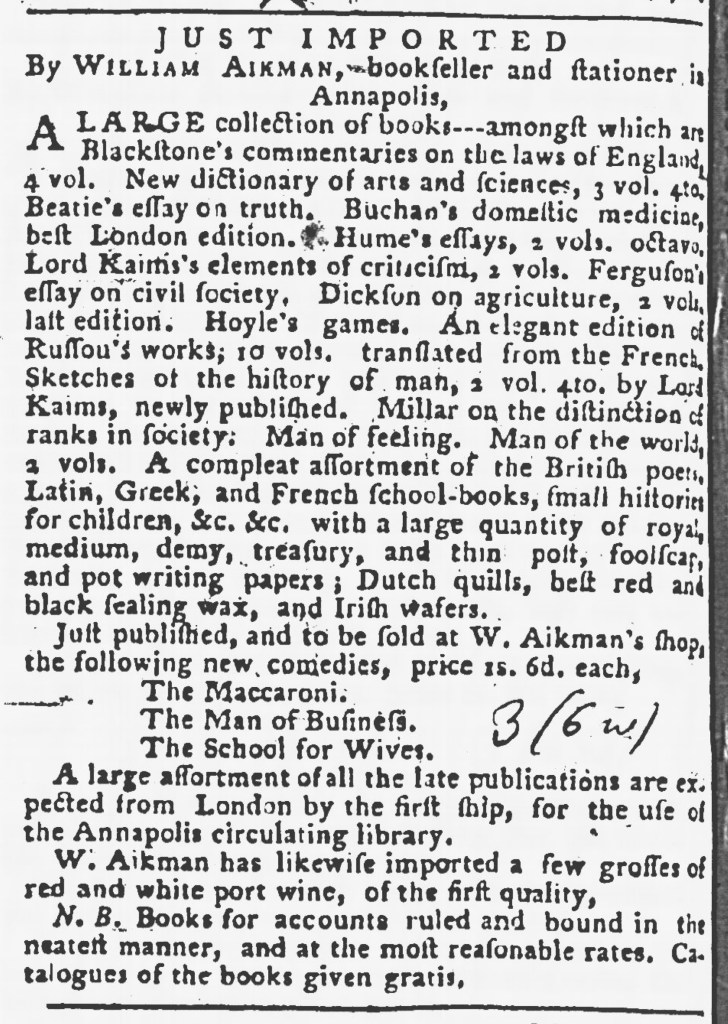

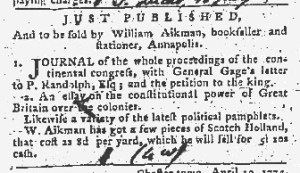

An advertisement by William Aikman, a bookseller and stationer in Annapolis, in the April 13, 1775, edition of the Maryland Gazette proclaimed, “JUST PUBLISHED, And to be sold … JOURNAL of the whole proceedings of the continental congress” and “An essay on the constitutional power of Great Britain over the colonies.” While Aikman no doubt sold those items, they had not been “JUST PUBLISHED,” nor had he published them.

Readers understood that “JUST PUBLISHED” did not always mean that an item was hot off the presses; sometimes that phrase was a vestige of an advertisement originally composed and disseminated weeks or months earlier and printed once again without revisions. Readers also understood that “JUST PUBLISHED, and to be sold by” did not necessarily mean that the retailer was also the publisher, merely that the retailer sold an item that had been published by someone, somewhere. Keeping that in mind yields a better understanding of the production and dissemination of the items that Aikman advertised.

Although printers in many towns, including Anne Catharine Green and Son in Annapolis, produced and advertised local editions of the Extracts from the Votes and Proceedings of the American Continental Congress in the weeks after the First Continental Congress concluded its meetings in Philadelphia near the end of October 1774, only two printing offices published the complete Journal of the Proceedings of the Congress in the following months. William Bradford and Thomas Bradford printed an edition in Philadelphia, as did Hugh Gaine in New York. Aikman most likely stocked and advertised the Bradfords’ edition, especially considering that they also printed John Dickinson’s Essay on the Constitutional Power of Great-Britain over the Colonies in America in 1774. Gaine did not publish a New York edition of that volume.

Aikman’s advertisement also stated that he carried “a variety of the latest political pamphlets,” but he did not list additional titles. Perhaps he followed the lead of James Rivington in New York and tried to profit from selling pamphlets “on both sides, in the unhappy dispute with Great-Britain.” As the imperial crisis reached its boiling point in April 1775, Aikman took to the pages of the Maryland Gazette to hawk two items published by the Bradfords in 1774 that became more timely and relevant as well as the “latest political pamphlets” that provided even more for colonizers to consider as they learned about and participated in current events.