What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

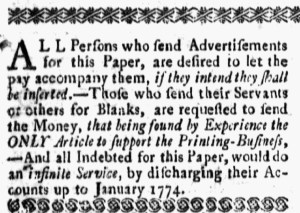

“Several Pieces from our Correspondents, Advertisements, &c. which came to Hand too late for this Day’s Paper, will be in out next.”

Timothy Green, the printer of the Connecticut Gazette, inserted a brief notice in the February 11, 1774, edition to advise that “Several Pieces from our Correspondents, Advertisements, &c. which came to Hand too late for this Day’s Paper, will be in out next.” In a few short lines, the printer aimed to manage his relationships with subscribers, advertisers, and anyone who submitted news, editorials, essays, or any other content for the newspaper. He suggested to readers that he worked until the last possible moment to include the latest news. He assured advertisers that their notices would indeed appear in print in the next issue. He let those who provided content know that practical matters, not a lack of appreciation for their efforts, played the deciding role in why their submissions did not appear alongside a proclamation from the governor, resolutions from a “Town-Meeting of the Town of Providence” concerning a “Duty upon Tea” enacted by Parliament, and an account of events that resulted in the tarring and feathering of John Malcom, a customs officer, in Boston.

Green’s notice appeared at the bottom of the final column on the third page. While that may seem like a curious place to modern readers, it made absolute sense to eighteenth-century readers, especially anyone familiar with the process for printing newspapers. The Connecticut Gazette, like other newspapers of the era, consisted of four pages, created by printing two pages on each side of a broadside and folding it in half. Workers in a printing office set the type for the first and fourth pages, printed the side of the broadsheet that featured those pages, and let the ink dry before printing the second and third pages on the other side. That meant that type for the interior pages was set last, so news received most recently, regardless of its magnitude, appeared there rather than on the front page. Whatever appeared at the end of the last column on the third page was the final bit of content that printers managed to fit in that issue. That Green’s notice appeared there testified to his efforts to publish everything received in his printing office in New London up to the moment he had to take that issue to press and distribute the February 11 edition on schedule.