What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

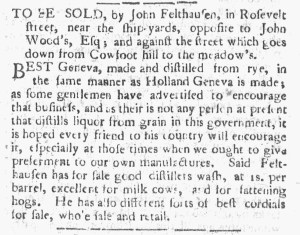

“BEST Geneva, made and distilled from rye.”

Advertisements for consumer goods and services crowded the pages of early American newspaper. Did they work? Unfortunately, that question is difficult to answer. The advertisements reveal what kinds of marketing appeals merchants, shopkeepers, artisans, and other entrepreneurs thought would resonate with consumers and influence them to make purchases, but they rarely indicated how readers responded.

That so many entrepreneurs advertised and that they invested in advertising regularly suggests that they believed that they received a sufficient return on their investment to make the expense worth it. Consider John Felthausen and his advertisement for “BEST Geneva [or Jenever, a type of gin], made and distilled from rye,” in the January 31, 1776, edition of the Constitutional Gazette. That was not the first time that Felthausen placed that advertisement. Three months earlier, he ran an advertisement with nearly identical copy in the New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury. If Felthausen believed that previous advertisement had not yielded results, would he have run it again in another newspaper a few months later?

That new advertisement had nearly identical copy, though the compositor for the Constitutional Gazette made very different decisions about the format than the compositor for the New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury. Felthausen may have even clipped the advertisement from one newspaper and delivered it to the printing office for the other, making marks on it to indicate copy he wished to update. Those revisions amounted to adding a sentence at the end: “He has also different sorts of best cordials for sale, wholesale and retail.” He retained his appeal to “every friend to this country” to “encourage” or support his business, “especially at those times when we ought to give preferment to our own manufactures.” The distiller apparently believed that his previous advertisement met with sufficient success to merit repeating it to hawk both his “BEST Geneva” and additional products not previously included.