What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

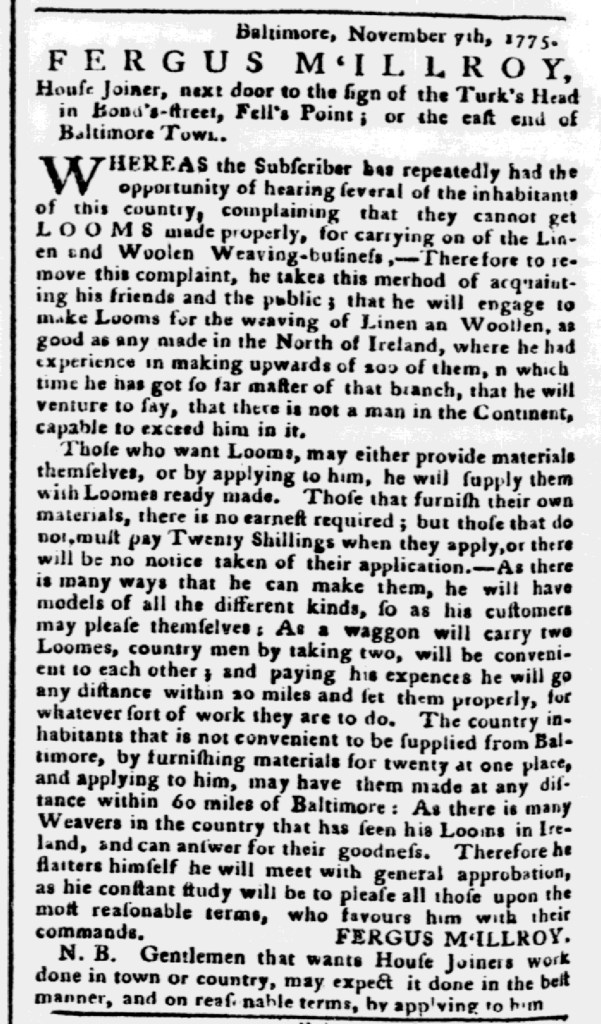

“He will engage to make Looms for the weaving of Linen an[d] Woollen.”

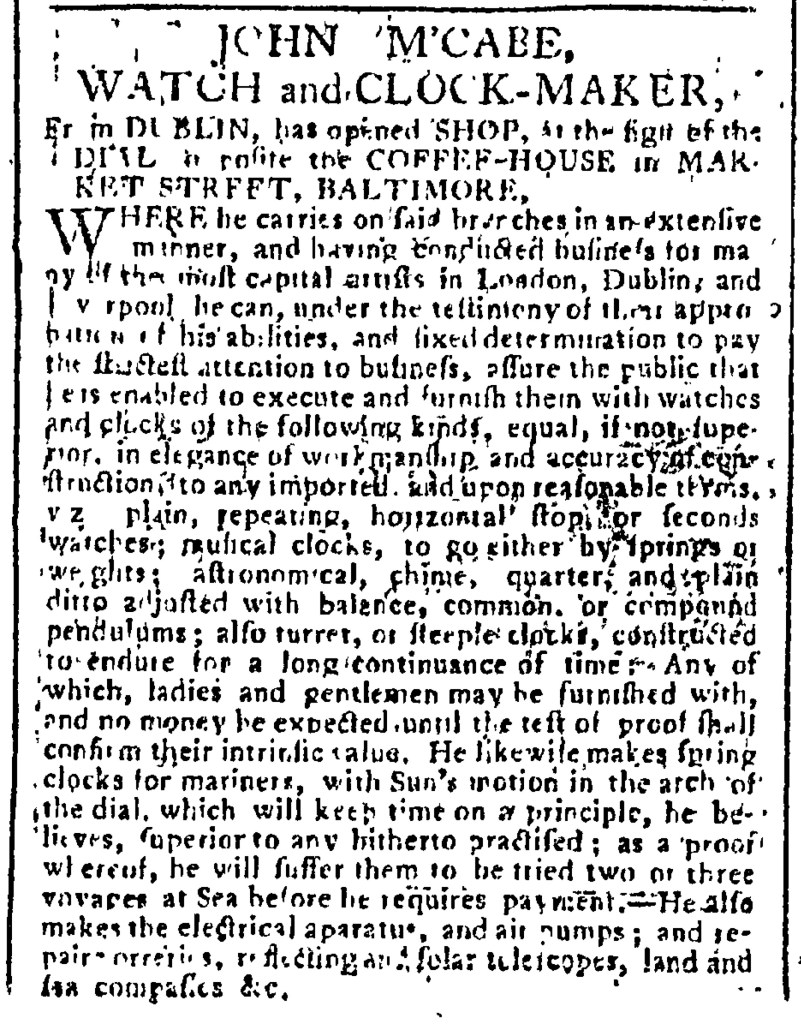

At the same time that David Poe advertised that he “set up … the business of SPINNING WHEEL Making” in Baltimore in November 1775, Fergus McIllroy took to the pages of Dunlap’s Maryland Gazette to inform the public that he “will engage to make Looms for the weaving of Linen an[d] Woolen.” Both artisans responded to demand for equipment for making textiles that arose in response to the Continental Association, a nonimportation and nonconsumption agreement devised by the First Continental Congress to leverage commerce as a means of achieving political goals. The text of the pact stated that it would remain in place until Parliament repealed duties on tea and the Coercive Acts that punished Boston for the destruction of tea in what has become known as the Boston Tea Party. It also issued a call to “encourage Frugality, Economy, and Industry; and promote Agriculture, Arts, and the Manufactures of this Country, especially that of Wool.”

Many colonizers, both men and women, wanted to do their part in producing domestic manufactures as alternatives to imported textiles and other goods, but they needed materials and equipment. McIllroy reported that he “repeatedly had the opportunity of hearing several of the inhabitants of this country, complaining that they cannot get LOOMS made properly, for carrying on of the Linen and Woolen Weaving-business.” Although he currently worked as a “House Joiner,” he claimed that he “has experience of making upwards of 200” looms before he migrated to Baltimore. That being the case, he pledged that his looms were “as good as any made in the North of Ireland.” Yet prospective customers did not have to take his word for it: “there is many Weavers in the country that has seen his Looms in Ireland, and can answer for their goodness.” For good measure, he added that he was a “master” when it came to making looms and “there is not a man in the Continent capable to exceed him.”

In addition, McIllroy noted the “many ways that he can make them,” so he had “models of all the different kinds, so as his customers may please themselves.” Furthermore, they could supply the materials for constructing their looms or leave it to McIllroy to provide the materials. In the latter instance, customers had to pay a deposit of twenty shillings before McIllroy would make their loom. He also outlined the conditions for visiting homes to “set them up properly.” If a town within sixty miles of Baltimore wished to order twenty or more looms, he offered to do the work there to avoid transporting the new looms over long distances. McIllroy stood ready to contribute to the American cause with his “Industry” that in turn “promote[d] … the Manufactures of this Country,” joining with other artisans who vowed to do the same.