What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“He is determined to be regularly supplyed with all the news-papers on the Continent.”

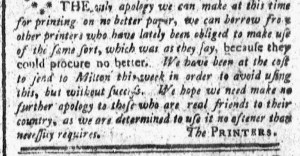

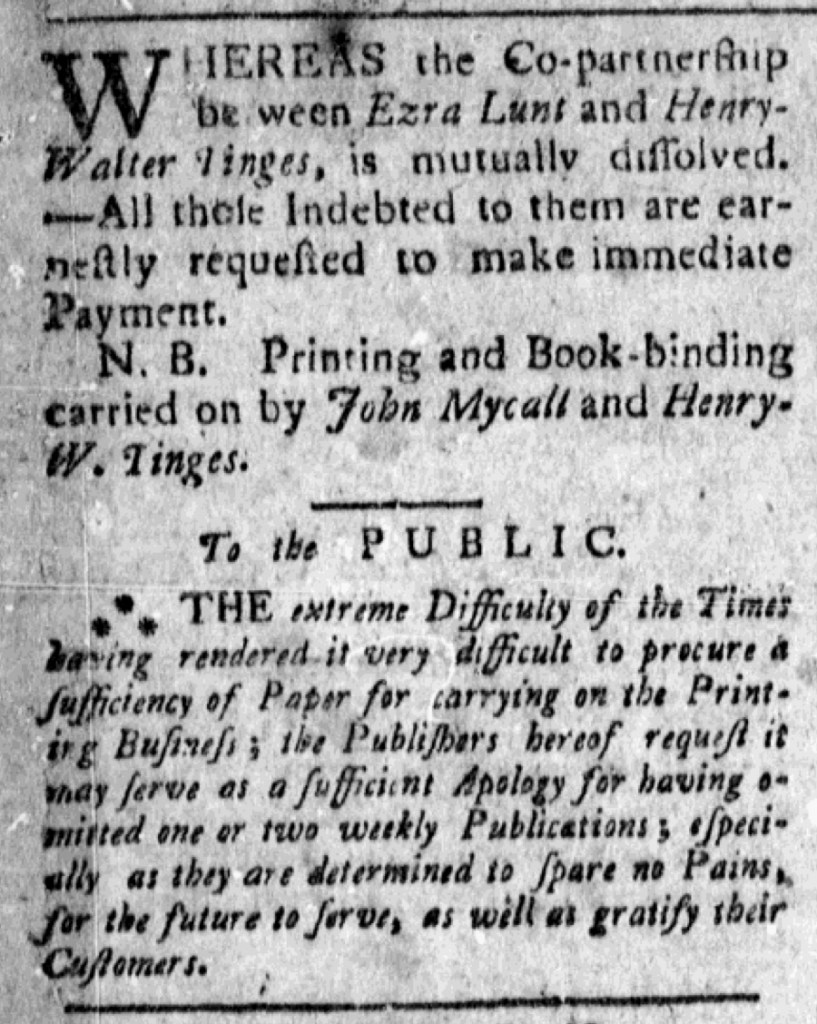

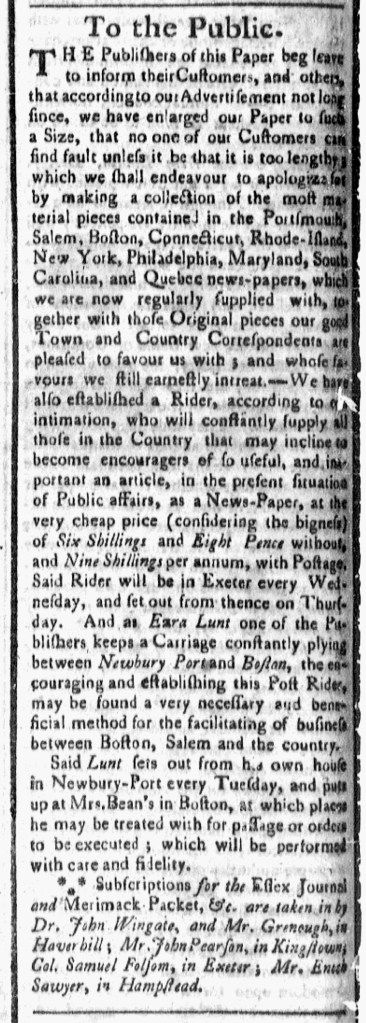

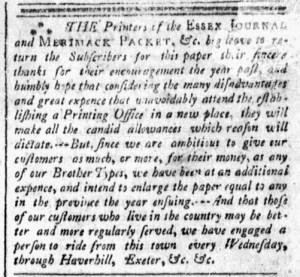

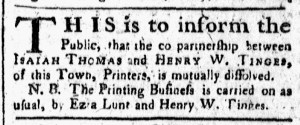

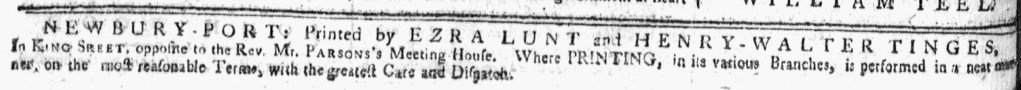

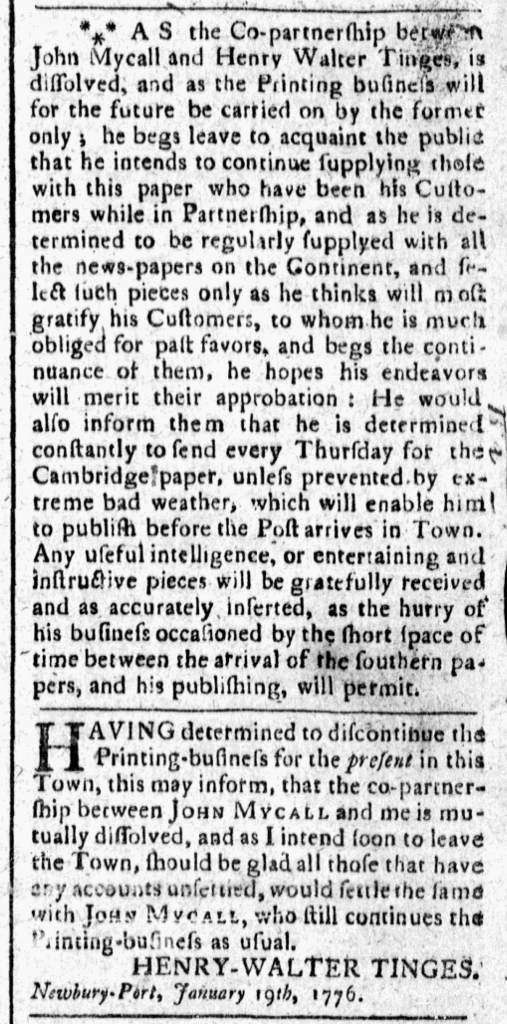

On January 19, 1776, John Mycall and Henry-Walter Tinges, the printers of the Essex Journal, announced the end of their partnership. Tinges had been a founding partner, commencing publication of the newspaper in Newburyport, Massachusetts, in collaboration with Isaiah Thomas, the printer of the Massachusetts Spy, in December 1773. As the junior partner, Tinges oversaw the printing office, including publication of the Essex Journal, in Newburyport, while Thomas tended to his printing office in Boston. That initial partnership lasted only eight months before Thomas withdrew and Tinges began a new partnership with Ezra Lunt in August 1774. That partnership also lasted less than a year. In July 1775, Lunt exited and Mycall joined as Tinges’s new partner. Seven months later, Tinges announced that he “determined to discontinue the Printing-business for the present in this Town” and the “co-partnership between JOHN MYCALL and me is mutually dissolved,” though Mycall “still continues the Printing-business as usual.” Mycall published the Essex Journal on his own for just over a year. It folded in February 1777, one of several newspapers that ceased publication during the Revolutionary War.

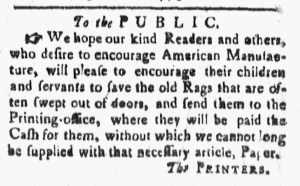

For his part, Mycall inserted his own advertisement stating that the partnership ended and that he “intends to continue supplying those with this paper who have been his Customers while in partnership.” He outlined his plan for supplying subscribers with news, declaring that he “is determined to be regularly supplyed with all the news-papers on the Continent, and select such pieces only as he thinks will most gratify his Customers.” That was the common practice for generating content in printing offices throughout the colonies. Printers participated in extensive exchange networks, liberally reprinting, word for word, items that appeared in the newspapers they received. Thus an item originally published in a newspaper in Charleston, for instance, could be reprinted from newspaper to newspaper in Williamsburg, Baltimore, Philadelphia, New York, Hartford, and Boston before appearing in the Essex Journal in Newburyport. Mycall made a point that he would “send every Thursday for the Cambridge paper, unless prevented by extreme bad weather, which will enable him to publish before the Post arrives in Town.” He referred to the New-England Chronicle, published Samuel Hall and Ebenezer Hall in Cambridge, Massachusetts. During the siege of Boston, most of the newspapers previously printed in that city ceased or suspended publication or moved to other towns. The Halls relocated the Essex Gazette, published in Salem, to Cambridge and renamed it the New-England Chronicle when it became the new paper of record for the latest news about the Massachusetts government and the Continental Army under the command of George Washington. Mycall underscored that he quickly received the latest edition of the New-England Chronicle, printed on Thursdays, and incorporated “useful intelligence” into the Essex Journal, published on Fridays, ahead of the schedule for post riders to arrive in Newburyport. In the eighteenth century, Mycall delivered breaking news to readers of the Essex Journal.