GUEST CURATOR: Emma Guthrie

What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

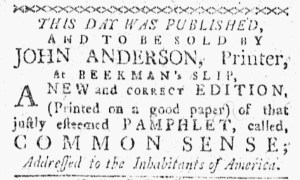

“A NEW and CORRECT EDITION, (Printed on a good paper) of … COMMON SENSE.”

This advertisement for “COMMON SENSE” promoted a pamphlet written by Thomas Paine. In one of the most important documents in American history, Paine argued for the independence of the colonies from Great Britain. John Anderson, a printer in New York, published this edition of Common Sense. He noted that his edition was “Printed on a good paper.”

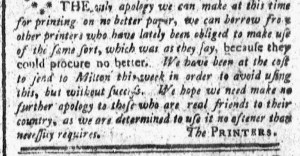

Due to the nonimportation agreements of the 1760s and 1770s, “the residual of imported paper was nearly exhausted” when the Revolutionary War began in 1775.[1] Paper used in printing pamphlets and newspapers had been an incredibly common import. However, due to the nonimportation agreements, paper became a scarce commodity. According to Eugenie Andruss Leonard in “Paper as a Critical Commodity during the American Revolution,” the domestic manufacture of paper was not sufficient and could not keep up with the demand for the product.[2] Anderson attempted to make his “NEW and CORRECT EDITION” of Common Sense stand out by stating that it was printed on “good paper,” enticing readers to purchase his pamphlet without having to worry about the quality of the printing and, especially, the paper.

**********

ADDITIONAL COMMENTARY: Carl Robert Keyes

I was excited when Emma selected Anderson’s advertisement for his edition of Common Sense to feature on the Adverts 250 Project. I encouraged students enrolled in my capstone research seminar in Fall 2025 to peruse previous entries in the project, but I did not discuss with them which advertisements I planned to feature in the coming months. When Emma chose this advertisement, she did not know that I would craft a series of entries about the marketing of Common Sense in the winter and spring of 1775.

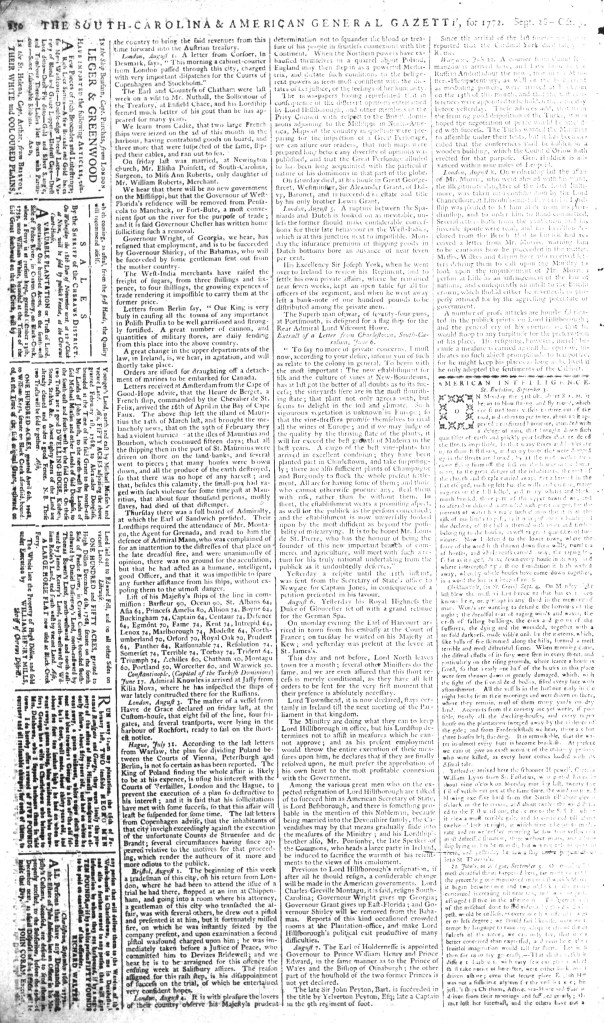

Emma could have selected any one of three advertisements for Common Sense that appeared in the February 8, 1776, edition of the New-York Journal. William Green inserted a version of the advertisement he originally placed in the January 22 edition of the New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury. Green stocked and sold Robert Bell’s unauthorized “Second Edition,” having previously advertised Bell’s first edition. Another advertisement encouraged readers to reserve copies of a “NEW EDITION (with LARGE and INTERESTING ADDITIONS …)” that Paine did authorize and entrusted to William Bradford and Thomas Bradford to print. Much of it replicated the advertisement that ran in the January 25 edition of the Pennsylvania Evening Post, including an address “To the PUBLIC” that explained that “the Publisher of the first edition” printed a second edition without the permission of the author. That edition would not include the new material that Paine arranged for the Bradfords to feature in their edition. The advertisement in the Pennsylvania Evening Post also noted, “A German edition is likewise in the press,” acknowledging the significant population of German settlers in Pennsylvania and the backcountry. The version in the New-York Journal, however, changed that note to “A Dutch Edition is likewise in the Press” for the benefit of those families who continued to speak Dutch a little more than a century after the English conquest of New Netherland.

Anderson’s advertisement confirmed what he advertised in his own Constitutional Gazette the previous day: publication of a “NEW and CORRECT EDITION” of Common Sense. It was the first edition published outside Philadelphia. Given that the Bradfords’ edition was still “In the PRESS,” Anderson published a local edition of Bell’s edition. Describing it as “NEW” meant that it was a local edition and describing it as “CORRECT” indicated that Anderson had faithfully reproduced the contents of the original pamphlet. Emma focused on another important aspect of Anderson’s advertisement. All the previous advertisements for Common Sense focused on the contents (especially those that listed the section headings) or the dispute between Bell and Paine and which edition readers should consider the superior one. Anderson was the first to focus on a material aspect of the pamphlet, assuring prospective customers that he used “good paper” when printing his local edition. The quality of the finished product rivaled any of the pamphlets shipped to New York from Philadelphia.

**********

[1] Eugenie Andruss Leonard, “Paper as a Critical Commodity during the American Revolution,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 74, no. 4 (October 195): 488.

[2] Larsen, “Paper as a Critical Commodity,” 488.