Who was the subject of an advertisement in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

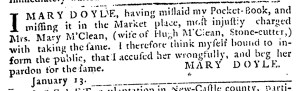

“I had not just cause to attack her reputation in the manner I have published.”

It was a rare retraction. James Harding instructed William Bradford and Thomas Bradford, printers of the Pennsylvania Journal, to discontinue an advertisement in which he advised the community against extending credit to his wife, Margaret.

James did not reveal the circumstances the prompted him to place his first advertisement in the March 3, 1773, edition of the Pennsylvania Journal. In that notice, he succinctly declared, “LET no Person credit my Wife, MARGARET HARDING, on my account, for I will pay none of her debts, after this date.” Throughout the colonies, aggrieved husbands regularly placed similar notices concerning recalcitrant wives. In many instances, they provided much more detail about how the women misbehaved or even “eloped” or abandoned their husbands. Without access to the family’s financial resources, controlled by each household’s patriarch, most wives could not publish rebuttals. Those who did offered very different accounts of marital discord and who was really at fault. For many women, running away was the most effective means of protecting themselves from abusive husbands.

Less than a week after placing the advertisement, James had a change of heart and sent instructions for the printers to remove the notice from subsequent issues. “HAVING published an advertisement in your last Paper, prohibiting persons from crediting my Wife, MARGARET HARDING, on my account,” James stated, “I do hereby, in justice to my Wife’s character, declare, that I had not just cause to attack her in the manner I have published.” Having reached that realization, he “therefore do forbid the continuance of said advertisement.” Once again, James did not go into details, though friends, neighbors, and acquaintance – women and men alike – probably shared what they knew and what they surmised as they gossiped among themselves.

James intended for his initial advertisement to run for a month, according to the “1 m,” a notation for the compositor, that followed his signature. In the end, that notice appeared just one before the Bradfords published his retraction in the March 10, 17, and 24 editions of the Pennsylvania Journal. Someone in the printing office may have felt some sympathy for Margaret. The retraction ran immediately below the “PRICES-CURRENT in PHILADELPHIA” on March 10, making it the first advertisement readers encountered as they transitioned from news items to paid notices. That likelihood increased the chances of readers noticing the retraction, even if they only skimmed the rest of the advertisement. Margaret did not share her side of the story in the newspaper, but it may have been some consolation that James’s acknowledgement that he erred in “attack[ing] her reputation” appeared repeatedly and the initial notice only once. That was more satisfaction than most women targeted by similar advertisements received from their husbands in the public prints.