What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“High Gaine has for sale, a great variety of books.”

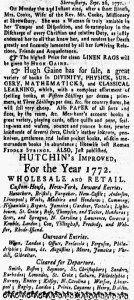

Although some colonial printers reserved the final pages of their newspapers for advertising, not all did so. In many newspapers, paid notices could and did appear on any page, including the front page. Such was the case in Hugh Gaine’s New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury. Consider the issue for October 7, 1771. Gaine divided the first page between news items and advertising, filling the first two columns with the former and the last two with the latter. He did the sane on the second page. On the third page, he arranged news in the first column and into the second, but the bottom half of the second column as well as the remaining two columns consisted entirely of advertising. Gaine gave over the entire final page to paid notices.

In general, Gaine placed news and advertising next to each other, but, like other printers who followed that method, he did not intersperse news and advertising on the page. He delineated space intended for news and space intended for advertising rather than having paid notices appear among news items and editorials … with one exception. He inserted an advertisement for books, stationery, and other items available at his printing office among the news on the third page. That advertisement appeared below a death notice for “Mrs. Cooke, Wife of the Rev. Mr. Cooke, Missionary at Shrewsbury,” and above the shipping news from the New York Custom House. A line of ornamental type then separated the news (and Gaine’s advertisement) from the advertisements that completed the column and filled the remainder of the page. In choosing this format, Gaine increased the likelihood that readers perusing the newspaper for news and skipping over the sections for advertising would see his own advertisement. He was not the only colonial printer who sometimes adopted that strategy, leveraging his access to the press to give his own advertisement a privileged place. Gaine inserted other advertisements elsewhere in the October 7 edition, most of them short notices intended to complete a column, but he exerted special effort in drawing attention to his most extensive advertisement by embedding it among the news. His customers who purchased space for their notices did not have the same option.