What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“A LARGE and neat ASSORTMENT of EUROPEAN and EAST-INDIA GOODS.”

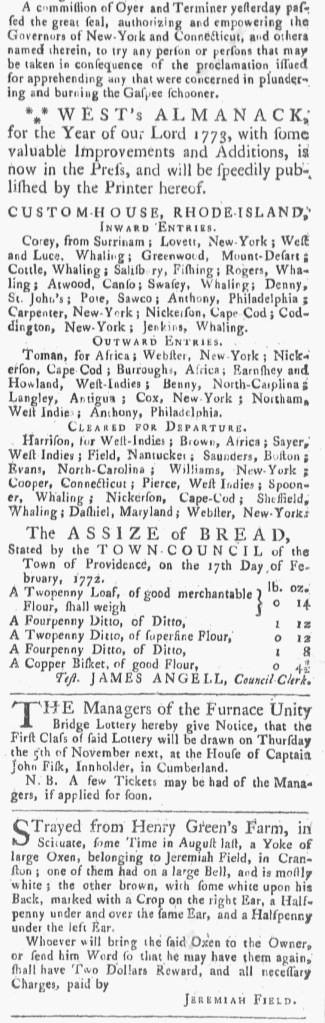

Most of the advertisements in the November 25, 1772, edition of the Pennsylvania Journal ran on the third and fourth pages. News occupied the first two pages and a portion of the third. Then the remainder of the issue featured paid notices, including an advertisement for a “Hearty, Strong NEGRO LAD” for sale, notices from ships seeking passengers and freight, and advertisements for consumer goods and services. William Bradford and Thomas Bradford, the printers, did not intersperse news and advertising … with one exception. Andrew Bunner’s brief advertisement advising that he “Just imported … A LARGE and neat ASSORTMENT of EUROPEAN and EAST-INDIA GOODS, suitable for the SEASON” appeared on the front page.

Consisting of only six lines, that advertisement ran at the bottom of the first column. The printers generated revenue by publishing Bunner’s notice, but they also treated it as filler that conveniently completed a column otherwise devoted to an essay about raising cattle submitted by a reader, “A RURAL RESIDENT.” The remainder of the column had enough space for the byline and a few lines of the news item that ran at the top of the second column, but the printers likely decided that readers would find that format confusing or less attractive than starting the news at the head of the column.

Did that work to Bunner’s advantage? He may have benefited from the unusual placement of his advertisement. Readers interested only in news and editorials may have only quickly glanced at the final pages of the newspaper, but when they reached the end of the letter about raising cattle on the first page they may have read through Bunner’s advertisement in expectation of more news rather than paid notices. Whether or not the placement enhanced the visibility of the notice, it certainly aided the printers in achieving even columns and a flow of news items easy for readers to navigate.