Who was the subject of advertisements in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“RUN-AWAY … a Negro man, named MINGO.”

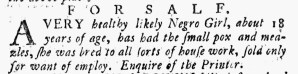

“FOR SALE, A VERY healthy Negro Girl.”

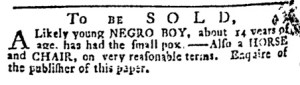

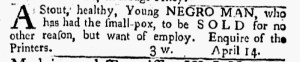

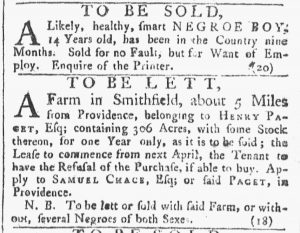

In the fall of 1775, John Anderson joined the ranks of newspaper printers who helped perpetuate slavery by disseminating advertisements about enslaved people in their publications. In this case, one advertisement concerned “a Negro man, named MINGO,” who liberated himself from Benjamin Hutchinson by escaping from Hutchinson of Southold in Suffolk County on Long Island in early October. The enslaver described the young man, both his physical features and his clothing, and offered a reward for his capture and return. Another advertisement offered a “healthy Negro Girl, about 18 years of age,” for sale. She was capable of “all sorts of house work” and sold “only for want of employ” rather than any deficiency.

Those advertisements first appeared in the October 25 edition of the Constitutional Gazette, a newspaper that commenced publication near the beginning of August. The new publication initially did not carry advertisements, though Anderson began soliciting them by the end of the month. Local entrepreneurs who had experience advertising in other newspapers, including goldsmith and jeweller Charles Oliver Bruff and Abraham Delanoy, who pickled lobsters and oysters, soon placed notices in the Constitutional Gazette. Beyond marketing consumer goods and services, others ran advertisements for a variety of purposes, replicating the kinds of notices found in other newspapers of the period.

That included advertisements about enslaved people. Two months after first soliciting advertisements (and less than three months after publishing the inaugural issue), Anderson disseminated Hutchinson’s advertisement about Mingo’s escape from slavery and another notice offering an enslaved young woman for sale. Like printers from New England to Georgia, he compartmentalized the contents of his newspaper, not devoting much thought to the juxtaposition of news and editorials advocating on behalf of the American cause and advertisements placed for the purpose of perpetuating slavery and the slave trade.

Even as Anderson used his newspaper to advocate for liberty for colonizers who endured the abuses perpetrated by Parliament, he used it to constrain the freedom of Black men, women, and children. The advertisement about Mingo encouraged readers to engage in surveillance of Black men to determine if any they encountered matched his description. In addition to publishing advertisements about enslaved people, Anderson also served as a broker. The advertisement for the young enslaved woman whose name was once known instructed interested parties to “Enquire of the Printer.” Anderson did more than merely disseminate information. He actively participated in the sale of the young enslaved woman as one of the services he provided as printer.