What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

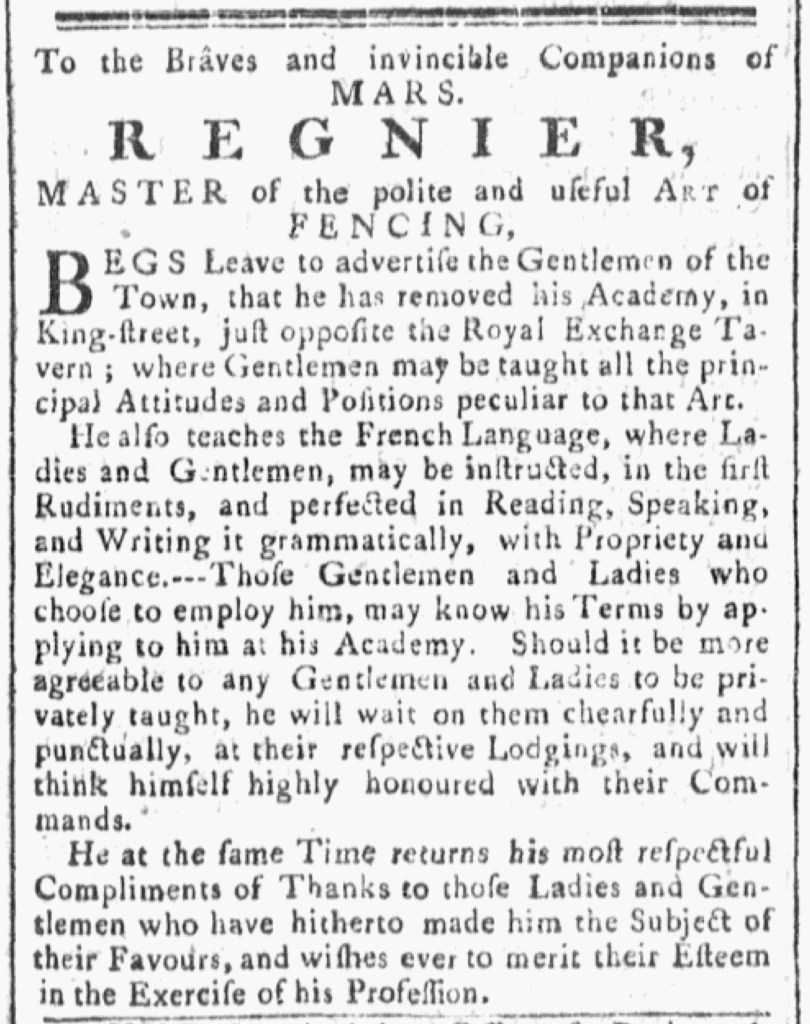

“The polite and useful ART of FENCING.”

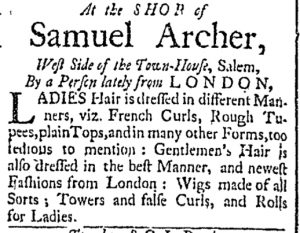

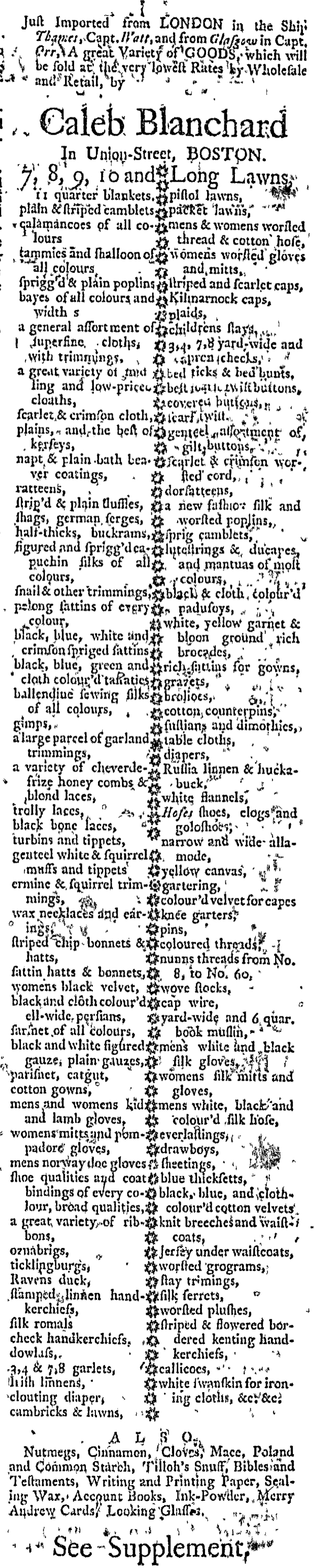

Two fencing masters dueled for pupils in the pages of the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Post-Boy in June 1774. Each of them addressed prospective students with a flourish. Donald McAlpine called on “all Lovers of the noble Science of DEFENCE,” while Monsieur Regnier, “MASTER of the polite and useful ART of FENCING,” was even more elaborate in addressing “the Braves and invincible Companions of MARS.” Those headlines set their advertisements apart from others that read “TO BE SOLD” or “SPRING GOODS” or “THOMAS YOUNG.”

McAlpine specialized in teaching “the Art commonly called the BACKSWORD,” a “Science” that he would impart to the “entire Satisfaction” of “GENTLEMEN who choose to be instructed” by him. He offered lessons on King Street from the early morning, commencing at sunrise, through the early evening, concluding with sunset, with a few hours set aside for meals and conducting other business. He also visited gentlemen at their lodgings to give private lessons. McAlpine indicated that he previously instructed “Gentlemen who have encouraged him” in his endeavor, while suggesting that he might not remain in Boston if other pupils did not engage his services. He claimed that he “is strongly urged to go to another place” to teach the gentlemen there, yet it “would be most agreeable to him” to remain in Boston. That would only happen, however, if he “Meets with such further Encouragement and Approbation” to convince him to stay. If any gentlemen who considered themselves “Lovers of the noble Science of DEFENCE” had hesitated in seeking out McAlpine’s services, they needed to remedy that soon or risk him moving to another city.

That appeal might have been more effective if Regnier had not simultaneously advertised that he taught fencing at “his Academy, in King-street, just opposite the Royal Exchange Tavern.” He bestowed on his pupils “all the principal Attitudes and Positions peculiar to that Art.” He made clear that learning to fence was not solely about using a sword but also entailed attaining graceful comportment that distinguished pupils as they pursued their everyday activities beyond his school. To that end, he also taught French to both ladies and gentlemen, asserting that his pupils learned to read, speak, and write “with Propriety and Elegance.” Regnier’s students became more genteel thanks to his lessons. In addition, they could feel more confident in putting these markers of sophistication on display thanks to the careful instruction they received. Like McAlpine, Regnier extended “his most respectful Compliments of Thanks” to those “who have hitherto made him the Subject of their Favours.” Such remarks did more than reveal his success in cultivating a clientele in Boston; they also suggested to anyone who had not previously taken lessons or thought that they might benefit from brushing up that they needed to engage Regnier’s services to keep up with friends and acquaintances who already had the good sense to hire him.

As they competed with each other for pupils, McAlpine and Regnier also subtly encouraged the ladies and, especially, gentlemen they addressed to think of themselves in competition with each other. Those “Lovers of the noble Science of DEFENCE” and those “invincible Companions of MARS” could enhance their social standing through displays of fencing, but they needed instruction from masters of the art to develop and to refine their skills. More than mere lessons, McAlpine and Regnier marketed a means for achieving and demonstrating status.