What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this month?

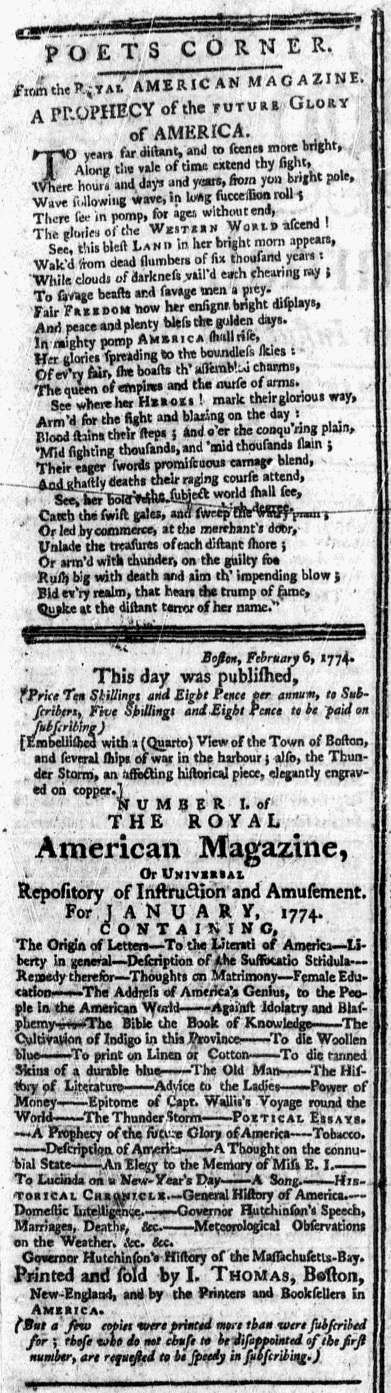

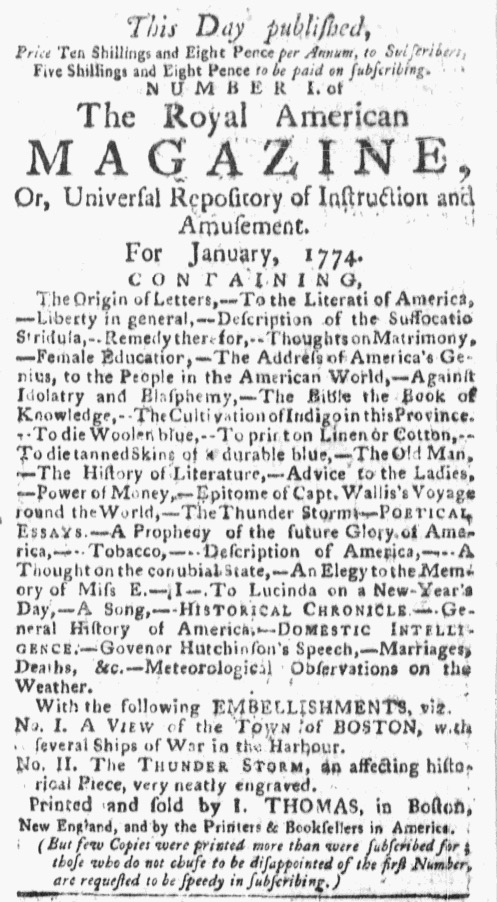

“NUMBER I. of The Royal AMERICAN MAGAZINE.”

February 1774 was an important month for Isaiah Thomas and the Royal American Magazine. The enterprising printer of the Massachusetts Spy first announced his intention to publish a magazine in May the previous year. At the time, no other magazines were published in the colonies. Instead, colonizers purchased and read magazines that printers and booksellers imported from England. Over the past several decades, American printers attempted to establish magazines, but most lasted about a year before folding. Hoping for better results, Thomas marketed the Royal American Magazine in newspapers from New Hampshire to Maryland. The Adverts 250 Project has traced his advertising campaign throughout June, July, August, September, October, November, and December 1773 and January 1774. This entry provides an overview of advertisements for the Royal American Magazine published in February 1774.

All the advertisements for that month ran in newspapers published in Boston or the Essex Journal, the newspaper that Thomas recently began publishing in partnership with Henry-Walter Tinges in Newburyport. During the months that Thomas attempted to drum up sufficient demand to make publishing the Royal American Magazine a viable endeavor, the subscription proposals and other notices appeared in newspapers far and wide. Once he took the magazine to press, however, he apparently did not consider it necessary to advertise as widely. Perhaps he was satisfied, for the most part, with the number of subscribers, though his advertisements did continue to encourage others to subscribe or risk missing out on the first issue.

In the February 2 edition of the Essex Journal, Thomas repeated, for the last time, an advertisement that explained the delay in publication of the first issue, originally planned for January. The next day, he announced in his own newspaper that the magazine would be published the following Monday. On that day, February 7, variant notices appeared in the Boston-Gazette and the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Post-Boy, both announcing that Thomas had indeed published the first issue of the Royal American Magazine. The same notice ran in the Boston-Gazette a week later, the last time that newspaper carried an advertisement about the new magazine that month.

A few days later, the first two of four variants of longer advertisements ran in the Massachusetts Spy and the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter. The version in Thomas’s own newspaper led with the price, promoted the copperplate engravings that accompanied the issue, listed the contents, and warned those who had not yet subscribed that they risked missing out on the inaugural issue. A shorter version in the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter included the contents and listed the engravings, but did not carry the other material. That was the only appearance of that variant. As the month progressed, that newspaper published a third variant that first ran in the Boston Evening-Post on February 14. It made all the same appeals as the one in the Massachusetts Spy, but in a different order. The Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Post-Boy, on the other hand, used the same copy as the Massachusetts Spy, perhaps as early as February 14 (that issue is missing) and in subsequent issues. On February 16, the Essex Journal carried its own variant, with the headline, “Lately PUBLISHED,” the only primary difference from the version in the Massachusetts Spy. Thomas likely dispatched the copy he used in Boston to his partner in Newburyport. Those two newspapers were the only ones that carried excerpts from the Royal American Magazine to entice readers. Except for the Boston-Gazette, each of the newspapers published in Boston carried one of the longer advertisements more than once in February.

Midway through the month, in an advertisement in the Massachusetts Spy, Thomas ran yet another advertisement, that one asking “Gentlemen” to submit essays for the magazine because “Numb. II. is now in the Press.” There was still time for new submissions to appear, but only if they were “sent with all speed” to Thomas’s printing office. That February issue would not be available until March. Thomas continued disseminating newspapers advertisements via the public prints, seeking to enhance the visibility of the new magazine, secure its reputation, and attract additional subscribers.

**********

“Types are now arrived” Update

- February 2 – Essex Journal (fifth appearance)

“MONDAY next will be published”

- February 3 – Massachusetts Spy (first appearance)

“THIS DAY PUBLISHED” (shorter variant)

- February 7 – Boston-Gazette (first appearance)

- February 14 – Boston-Gazette (second appearance)

“This Day published” (variant promoting engravings)

- February 7 – Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Post-Boy (first appearance)

“NUMBER I” (contents and engravings variant)

- February 10 – Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter (first appearance)

“NUMBER I” (price, engravings, contents, and subscribers variant)

- February 10 – Massachusetts Spy (first appearance)

- February 14 – Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Post-Boy (possible first appearance)

- February 17 – Massachusetts Spy (second appearance)

- February 21 – Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Post-Boy (first known appearance; possible second appearance)

- February 24 – Massachusetts Spy (third appearance), accompanied by excerpt

- February 28 – Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Post-Boy (second known appearance; possible third appearance)

“NUMBER I” (price, contents, engravings, and subscribers variant)

- February 14 – Boston Evening-Post (first appearance)

- February 17 – Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter (first appearance)

- February 21 – Boston Evening-Post (second appearance)

- February 24 – Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter (second appearance)

“NUMBER I” (“Lately PUBLISHED” variant)

- February 16 – Essex Journal (first appearance)

- February 23 – Essex Journal (second appearance), accompanied by excerpt

“Numb. II. is now in the Press”

- February 17 – Massachusetts Spy (first appearance)