What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago this month?

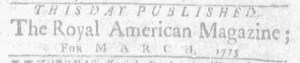

“THIS DAY PUBLISHED, The Royal American Magazine; FOR MARCH, 1775.”

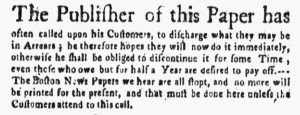

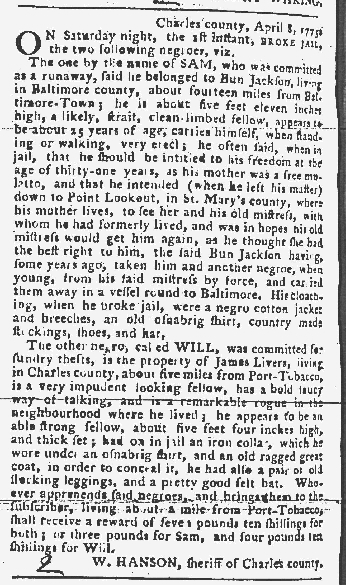

On April 28, 1775, Daniel Fowle, printer of the New-Hampshire Gazette, reported that the “Boston News Papers … are all stopt, and no more will be printed for the present” following the outbreak of hostilities at Lexington and Concord. He could have also mentioned that the Royal American Magazine, published by Joseph Greenleaf in Boston, had been suspended as well. Although some of the newspapers eventually resumed, the Royal American Magazine did not. The March 1775 issue, distributed in the second week of April, was the last one for that ambitious project that had repeatedly met with mishaps. Isaiah Thomas, the original publisher, delayed the first issue when the ship carrying new types ran aground in January 1774 and then fell several issues behind because of the “Distresses” that Boston experienced when the Boston Port Act closed the harbor in June 1774 in retaliation for the destruction of tea the previous December. Shortly after Thomas advised the public that he had suspended the magazine, he announced that he transferred it to Greenleaf. The new publisher worked diligently to compile, print, and circulate the overdue issues and get back on schedule.

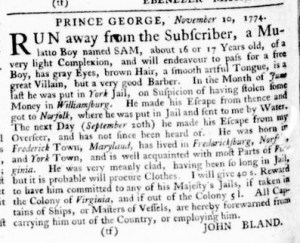

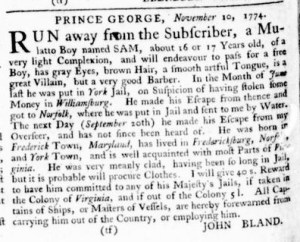

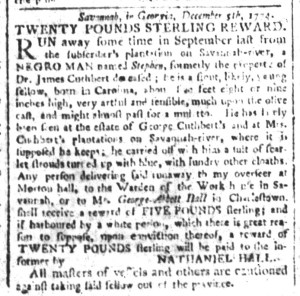

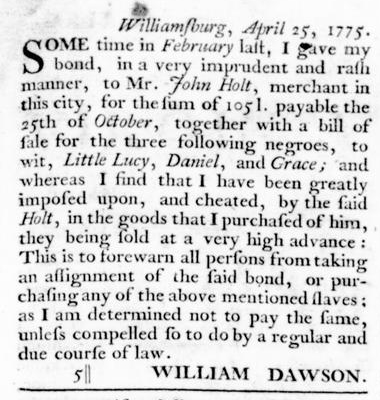

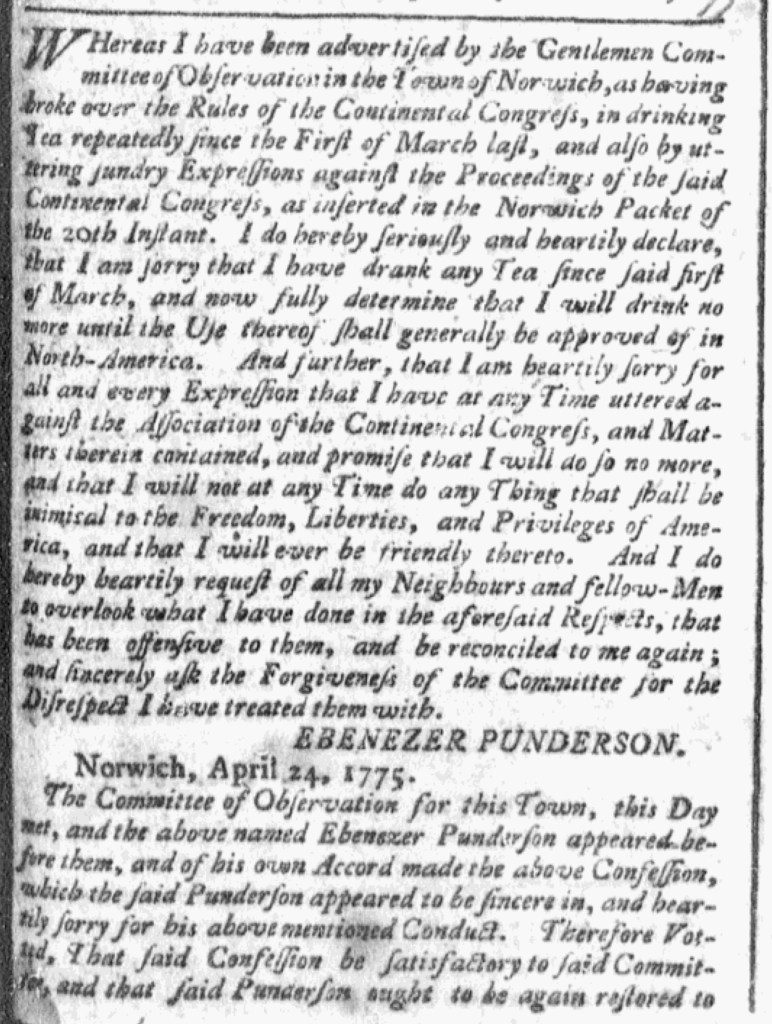

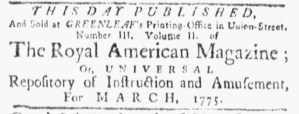

Despite the challenges, he managed to do so, especially considering that eighteenth-century subscribers expected the issue for a month either at the very end of that month or early in the following month. Accordingly, when Greenleaf first announced publication of the February 1775 issue on March 13 the new issue was on time, especially given the circumstances. A month later, he ran a brief notice in the April 13 edition of the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter: “THIS DAY PUBLISHED, The Royal American Magazine; FOR MARCH, 1775.” A week later, he placed a more extensive advertisement in the same newspaper. That one promoted the “elegant Engraving” that “Embellished” the magazine, though he did not reveal that it was a political cartoon depicting “America in Distress” engraved by Paul Revere. (See the American Antiquarian Society’s illustrated inventory of “Royal American Magazine Plates” for images and descriptions of Revere’s engravings that accompanied the magazine.) As he sometimes did in advertisements in previous months, Greenleaf stated that “Subscriptions continue to be taken in.” That advertisement appeared on April 20, the day after the battles at Lexington and Concord. Almost certainly Greenleaf composed the advertisement before such momentous events; very likely the type had already been set when word arrived in Boston. The Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter covered the “unhappy Affair” in a single paragraph that ran on the same page as the advertisement for the Royal American Magazine. It would be the last issue of that newspaper until May 19. On April 24, the final issue of the Boston Evening-Post carried only three advertisements, one of them announcing publication of the March issue of the Royal American Magazine.

That brought to conclusion an advertising campaign that lasted nearly two years when Thomas first declared that he would distribute subscription proposals. For several months, he advertised widely in newspapers in New England, New York, Pennsylvania, and Maryland, seeking subscribers in distant cities for what was the only magazine published in the colonies at the time. (Robert Aitken eventually launched the Pennsylvania Magazine in January 1775, a year after the Royal American Magazine commenced.) Thomas scaled back the advertising once he took the first issue of the magazine to press. In turn, Greenleaf also confined his advertising to Boston’s newspapers. The ambitious project ended up a casualty of the imperial crisis when resistance became revolution.

This entry concludes an ongoing series in which the Adverts 250 Project has tracked advertisements for the Royal American Magazine from Thomas’s first notice, in May 1773, that he planned to distribute subscription proposals to newspapers advertisements in June, July, August, September, October, November, and December 1773 and January, February, March, April, May, and June 1774. No magazine advertisements for the magazine appeared in July 1774 because of the “Distresses,” yet they resumed in August, September, October, November, and December 1774 and January, February, and March 1775.

**********

“THIS DAY PUBLISHED, The Royal American Magazine; FOR MARCH, 1775”

- April 13 – Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter (first appearance)

“JUST PUBLISHED … The Royal American Magazine … For MARCH, 1775”

- April 20 – Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter (first appearance)

“THIS DAY PUBLISHED … The Royal American Magazine … For MARCH, 1775.”

- April 24 – Boston Evening-Post (first appearance)