What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Greatly contribute towards the elevation and enlivening of Literary Manufactures.”

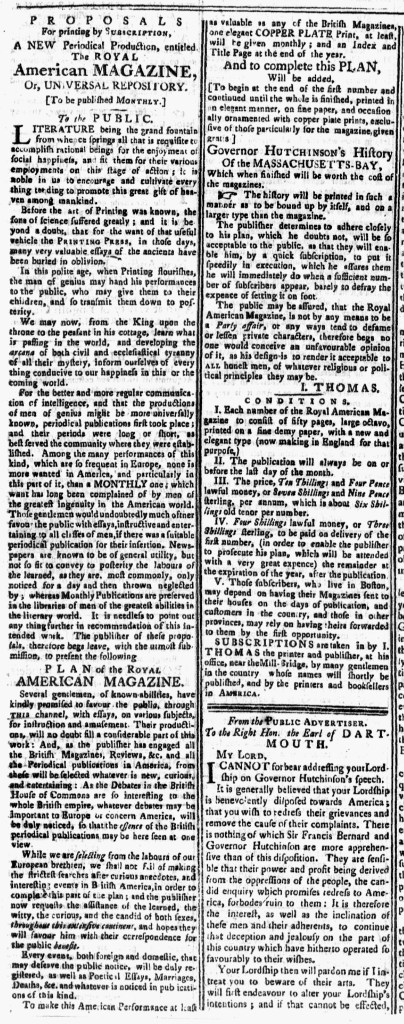

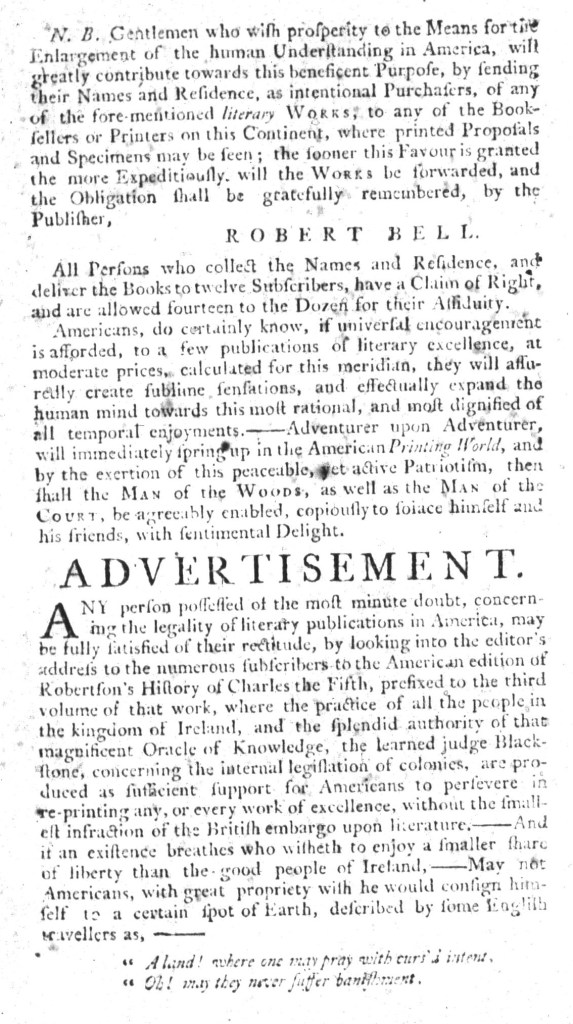

Both before and after the American Revolution, Robert Bell, one of the most influential publishers and booksellers of the eighteenth century, set about creating an American market for books. That did not always mean publications by American authors but rather editions printed in America for American readers. More than any other printer, publisher, or bookseller, Bell devised advertising campaigns that spanned the colonies in the early 1770s, distributing subscription proposals and inserting notices in newspapers from New England to South Carolina. His advertisement addressing “SAGES and STUDENTS of the LAW, in AMERICA,” for instance, appeared in newspapers in several colonies, promoting “American editions” of “celebrated works” undertaken by “ROBERT BELL, Printer and Bookseller, of Philadelphia.”

Readers of the Connecticut Gazette, published in New London, encountered Bell’s “SAGES and STUDENTS” advertisement in the January 21, 1774, edition. By then, the advertisement had been in circulation in various newspapers for several months as Bell attempted to cultivate a community of readers and consumers not bounded by local geography but instead defined by their common interest in “the elevation and enlivening of Literary Manufactures in America.” To that end, readers in New London and other places near and far had “had an opportunity of seeing at most of the booksellers shops in the capital towns and cities on the Continent, printed proposals with conditions and specimens” for “American editions” of several books, including “BACON’s new abridgment of the law,” “FERGUSON’s essay on the history of Civil Society,” and “A second American edition of Judge BLACKSTONE’s Commentaries on the laws of England.” For some of those books, Bell asserted that they matched “page for page with the last London edition,” yet he charged only half the price for the American edition. The savvy publisher wedded bargain prices and supporting American industry at a time when relations with Parliament deteriorated in the wake of the Tea Act.

To learn more about subscribing to these various American editions, prospective customers could view the conditions in the printed proposals as well as examine specimens (or samples) to confirm that the quality of the type, paper, and printing was not inferior to imported editions. Bell’s marketing efforts thus incorporated several media, not newspaper advertisements alone. Bell cultivated a network of printers and booksellers to disseminate his various forms of advertising in the public prints and in their printing offices and bookshops, enlisting distant associates in the project of encouraging a market for American editions of important and popular books.