What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

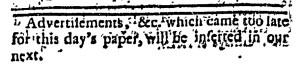

“(Advertisements omitted will be in our next.)”

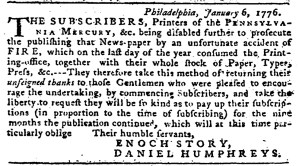

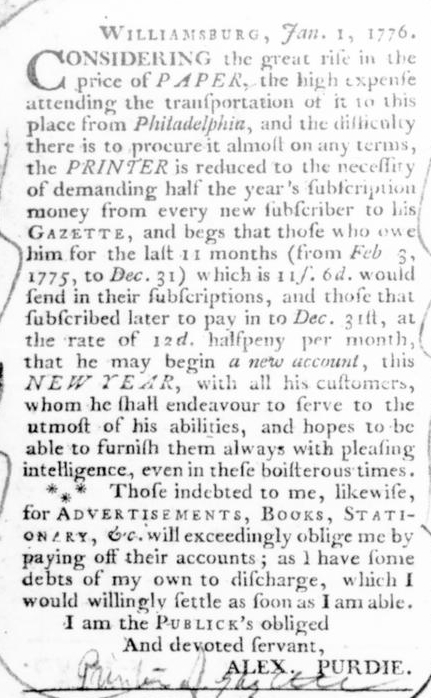

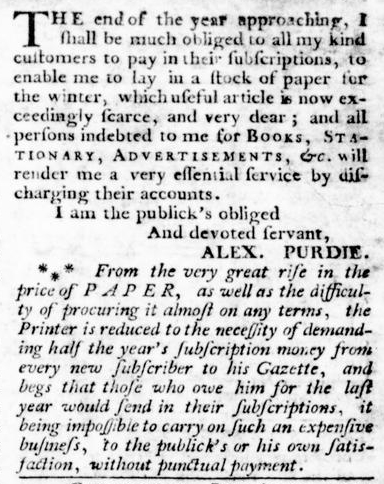

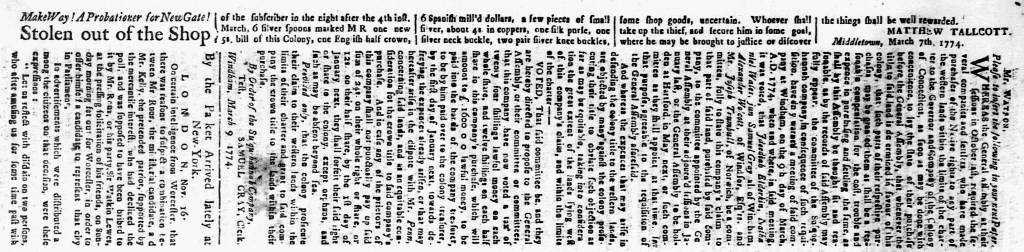

Instead of the usual four pages, the January 12, 1776, edition of the Connecticut Gazette consisted of only two pages. Most issues of colonial newspapers had four pages, created by printing two pages on each side of a broadsheet and folding it in half. Timothy Green, the printer of the Connecticut Gazette, had only enough paper that he was forced to condense the contents to a half sheet, one page printed on each side. He certainly was not the only printer to experience a disruption in his paper supply during the first year of the Revolutionary War.

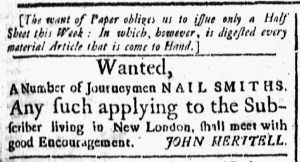

Green acknowledged the situation with a note that appeared at the top of the first column on the first page: “[The want of Paper obliges us to issue only a Half Sheet this Week: In which, however, is digested every material Article that is come to Hand.]” In other words, subscribers and other readers did not need to worry that they missed important news because Green did not have enough space to print it. Instead, he carefully undertook his duties as an editor to include everything of importance received in the printing office since the previous week’s issue of the Connecticut Gazette. The small font for news items, smaller than the font used for advertisements, also allowed Green to squeeze a significant amount of content into just two pages.

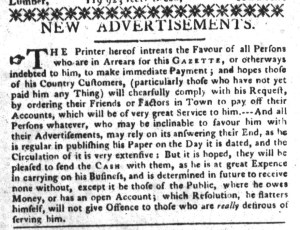

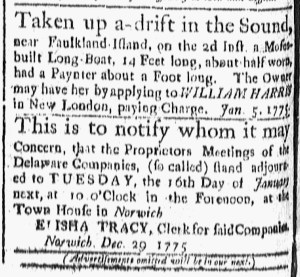

What about the advertisements? Only three paid notices appeared in that issue, one for “Journeyman NAIL SMITHS” immediately below the printer’s note on the first page and two more at the bottom of the final column on the second page. The printer concluded the issue with a brief note: “(Advertisements omitted will be in our next.)” Green assured advertisers, especially those who paid in advance of publication, that the Connecticut Gazette would indeed disseminate their notices. In this instance, however, he prioritized the needs of subscribers (many of whom did not make timely payments) and other readers (who did not pay the printer at all) over advertisers (who comprised an important revenue stream). It was a careful balancing act for all colonial printers as they served multiple constituencies simultaneously. For this issue, Green considered keeping subscribers and the rest of the public informed about “The King’s SPEECH, to both Houses of Parliament, October 26, 1775,” and news from London, Philadelphia, New York, Newport, Worcester, and Watertown (where the Continental Army continued the siege of Boston) more important than publishing many of the advertisements submitted to his printing office.