What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Shopkeepers are cautioned, not to advance on their Goods, which is contrary to the Resolves of the Continental Congress.”

The December 5, 1775, edition of the New-Hampshire Gazette consisted of only two pages rather than the usual four. That limited the amount of news and advertising that the printer, Daniel Fowle, could disseminate to readers, yet that issue carried good news that the “Printing Press is now again removed from Greenland to Portsmouth.” Fowle had moved his press to Greenland, about six miles from Portsmouth, to protect it from an anticipated British attack on New Hampshire’s most important port. In early December, he moved his press back to Portsmouth, “into an old Building adjoining the late Printing-Office … where it is hop’d the Types will remain undisturb’d, as this Harbour is so well fortified that any Enemy must pass thro’ a Hell of Fire, intermix’d with Brimstone, Pitch Tar, Turpentine, and almost every Sort of Combustible Matter to make the Passage dreadful.”

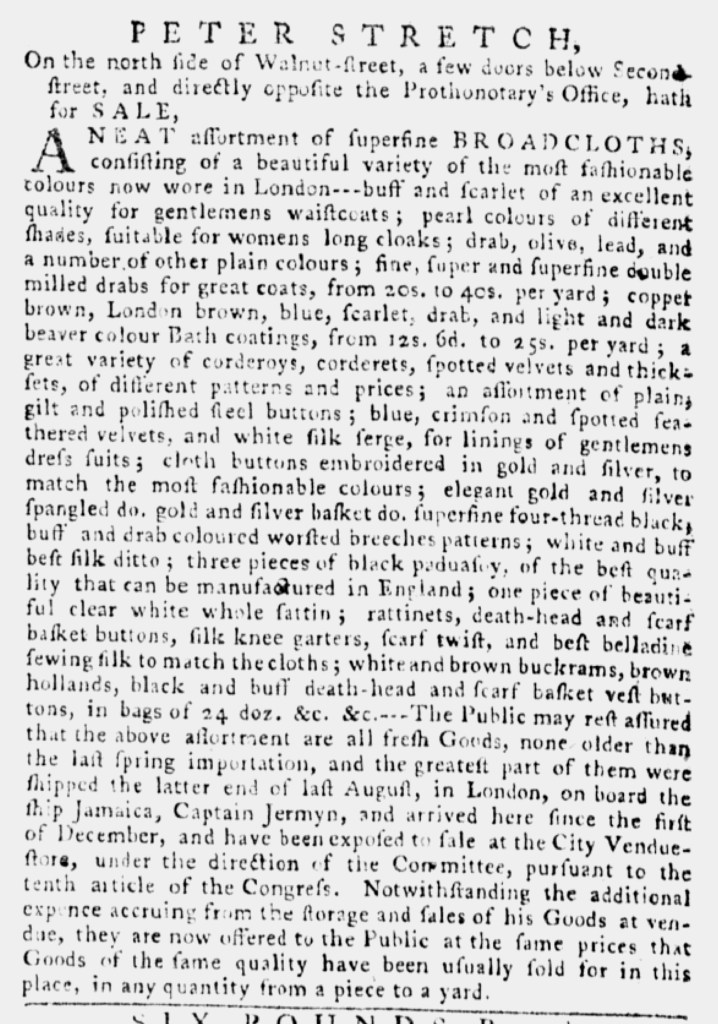

Yet enemies to the American cause did not approach Portsmouth solely by sea. Some enemies resided in the port and nearby towns, undermining efforts to resist British tyranny through their actions in the marketplace rather than on the battlefield. At the bottom of the last column on the last page, Fowle concluded that issue of the New-Hampshire Gazettewith a warning published “By desire” of a correspondent that “Shopkeepers are cautioned, not to advance on their Goods, which is contrary to the Resolves of the Continental Congress.” The correspondent invoked the ninth article of the Continental Association, a nonimportant agreement devised by the First Continental Congress that went into effect on December 1, 1774. That article stated that “such as are Venders of Goods or Merchandise will not take Advantage of the Scarcity of Goods that may be occasioned by this Association, but will sell the same at the Rates we have been respectively accustomed to do for twelve months past.” Some shopkeepers in and near Portsmouth apparently considered charging an “Advance” (or markup) on their wares, prompting the patriotic correspondent to remind them of the Continental Association and the consequences they faced. That would be their only warning because “if they do [raise prices], their Names will be return’d to the Congress ad publish’d, without further Notice.” Once that happened, the ninth article specified that “if any Venders of Goods or Merchandise shall sell any such Goods on higher Terms … no Person ought, nor will any of us deal with any such Person … at any Time thereafter, for any Commodity whatever.” That issue carried only two advertisements from local retailers, yet the address applied to all the shopkeepers in the vicinity.