What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

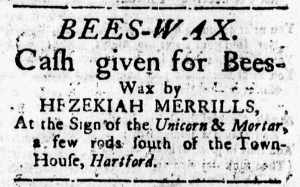

“At the Sign of the Unicorn & Mortar.”

Hezekiah Merrill ran an apothecary shop in Hartford in the early 1770s. In October 1773, he placed advertisements in the Connecticut Courant to promote the variety of patent medicines that he sold, including Bateman’s Drops and Cordials, Turlington’s Balsam of Life, and Hooper’s Female Pills. Each of those remedies would have been as familiar to eighteenth-century readers as popular over-the-counter medications are to modern consumers. Merrill, like others who sold the same patent medicines, did not believe that they required descriptions when advertising them. The apothecary also stocked books at his shop.

Merrill marked the location of his shop with “the Sign of the Unicorn & Mortar,” an appropriate image for an apothecary, and further advised prospective customers that they could find it “a few rods south of the Town-House.” Residents of Hartford regularly passed the shop and its sign, making it a familiar sight in their daily routines. For visitors from the countryside, the sign made Merrill’s location unmistakable as they navigated town. The apothecary encouraged consumers to associate the image of the Unicorn and Mortar with his business, treating it as a logo of sorts. He inserted two advertisements in the October 5, 1773, edition of the Connecticut Courant, both of them invoking his shop sign. A longer one on the first page listed the patent medicines and other merchandise, while a shorter one on the third page solicited beeswax in exchange for cash. Just as residents of Hartford frequently glimpsed the sign, readers of the Connecticut Courant encountered “the Sign of the Unicorn & Mortar” more than once when they perused that issue.

Today, those advertisements testify to some of the sights that colonizers saw as they traversed the streets of colonial Hartford. According to Thomas Hilldrup’s advertisement in the same issue of the Connecticut Courant, “the sign of the Dial” adorned the shop where he cleaned and repaired watches near the court house. Other purveyors of goods and services in Hartford almost certainly displayed signs, contributing to the visual landscape of commercial activity in the town. Few of those signs survive today, except for the descriptions of them in newspaper advertisements.