What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

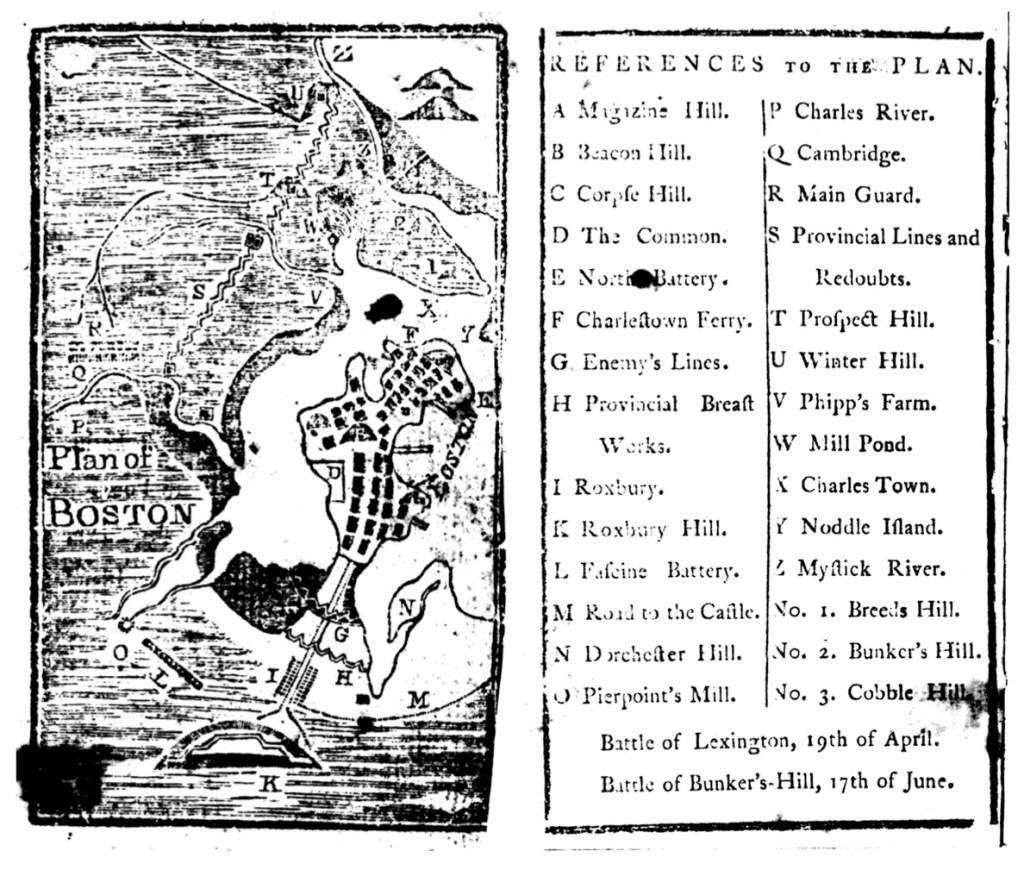

“MAPS … Montreal with all its fortifications. The city of Quebec.”

Robert Bell, one of the most prominent American booksellers of the eighteenth century, also sold “PLANS, MAPS, and CHARTS” at his shop in Philadelphia. In an advertisement in the November 7, 1775, edition of the Pennsylvania Evening Post, he promoted maps depicting “Montreal with all its fortifications. The city of Quebec. The river St. Laurence, with the operations of the siege of Quebec, under Admiral Saunders and the brave General Wolfe. The Harbour of Halifax. Nova Scotia. Canada. New Orleans, the capital of Louisiana, with the course of the river Mississippi. [And] The West-Indies.”

Bell moved from north to south, generally, in listing the places depicted on the maps and charts that he stocked and sold, though he seemingly made a deliberate decision to list Montreal and Quebec before Halifax. Current events likely influenced that choice. For its first major military initiative, the Continental Army launched an invasion of Quebec in hopes of capturing the province and convincing its inhabitants to join the American cause. That territory had been claimed by the French Empire for centuries, but only recently became part of the British Empire as part of the settlement that brought the Seven Years War to an end in 1763. The Americans suspected that French speakers in Quebec had little loyalty to the British.

Two expeditions conducted a dual-pronged attack on the province. In late August, an expedition authorized by the Second Continental Congress and commanded by General Richard Montgomery departed Fort Ticonderoga in New York, headed to Montreal. Colonel Benedict Arnold, disappointed at being passed over to lead that expedition, convinced General George Washington to send another expedition to Quebec City. Under Arnold’s command, that expedition departed Newburyport, Massachusetts, and made a harrowing journey up the Kennebec River.

At the time that Bell ran his advertisement, Montgomery’s expedition approached Montreal and Arnold’s expedition approached Quebec, though it would take some time for news to arrive in Philadelphia for readers of the Pennsylvania Evening Post. Yet those readers did know that those expeditions were underway and that Montgomery began a siege of the town and fort of Saint-Jean in September. Bell believed that some prospective customers were already interested in maps and plans of Montral and Quebec City and that he could incite demand among others by informing them of the items available at his shop. The maps he sold supplement the news that colonizers read in the public prints.