What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Those who are animated by the Wish of seeing Native Fabrications flourish in AMERICA.”

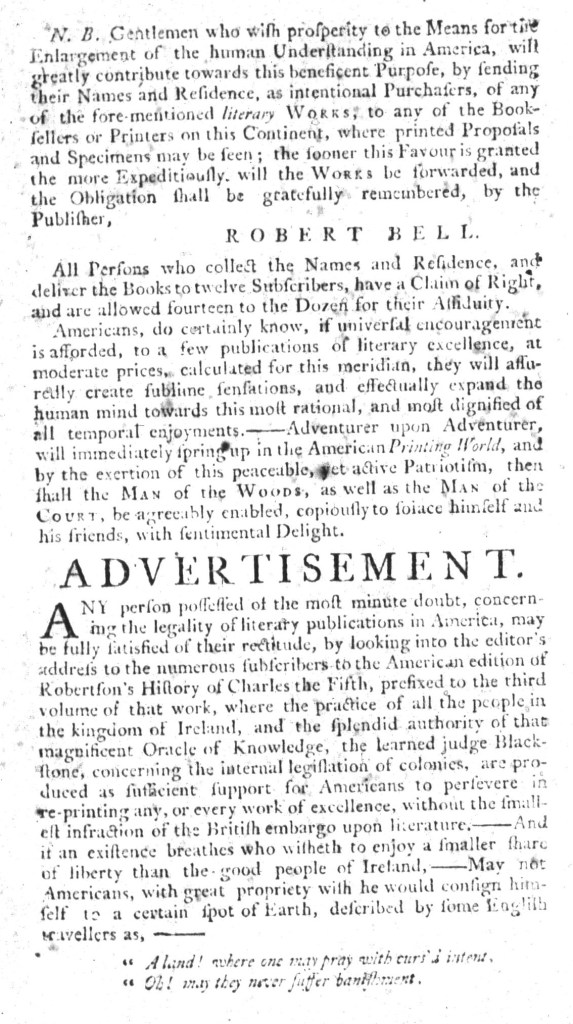

Robert Bell worked to create an American literary marketplace in the second half of the eighteenth century. The flamboyant bookseller, publisher, and auctioneer commenced his efforts before the American Revolution, sponsoring the publication of American editions of popular titles that other booksellers imported. His strategy included extensive advertising campaigns in newspapers published throughout the colonies. He established a network of local agents, many of them printers, who inserted subscription notices in newspapers, accepted advance orders, and sold the books after they went to press.

Those subscription notices often featured identical copy from newspaper to newspaper. For instance, Bell attempted to drum up interest in William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England in 1772. Advertisements that appeared in the Providence Gazette, the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal, and other newspapers all included a headline that proclaimed, “LITERATURE.” Bell and his agents tailored the advertisements for local audiences, addressing the “Gentlemen of Rhode-Island” in the Providence Gazette and the “Gentlemen of SOUTH-CAROLINA” in the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal. In each instance, though, they encouraged prospective subscribers to think of themselves as a much larger community of readers by extending the salutation to include “all of those who are animated by the Wish of seeing Native Fabrications flourish in AMERICA.”

Bell aimed to cultivate a community of American consumers, readers, and supporters of goods produced in the colonies, offering colonizers American editions of Blackstone’s Commentaries and other works “Printed on American Paper.” Given the rate that printers reprinted items from one newspaper to another, readers already participated in communities of readers that extended from New England to Georgia, but Bell’s advertisements extended the experience beyond the news and into the advertisements. He invited colonizers to further codify a unified community of geographically-dispersed readers and consumers who shared common interests when it came to both “LITERATURE” and “the Advancement” of domestic manufactures. To do so, they needed to purchase his publications.