What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“We have removed our Printing-Office from Salem to this Place.”

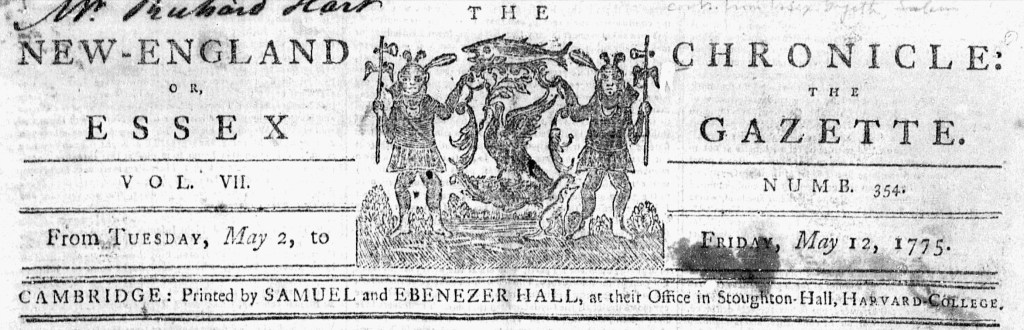

Sameul Hall and Ebenezer Hall printed the first issue of the New-England Chronicle: Or, the Essex Gazette “at their Office in Stoughton-Hall, HARVARD COLLEGE,” on May 12, 1775. As they explained in a notice to readers, “we have removed our Printing-Office from Salem to this Place” after receiving encouragement from “many respectable Gentlemen, Members of the Honourable Provincial Congress, and others.” They did so during the siege of Boston that followed the battles at Lexington and Concord on April 19. The several newspapers previously published in Boston either ceased or suspended publication, leaving Salem’s Essex Gazette as one of the only newspapers in the colony. The Provincial Congress, recognizing the value of having ready access to a press and a weekly newspaper, invited the Halls, already known as vigorous advocates of the patriot cause, to join them in Cambridge. When the Halls commenced printing the New-England Chronicle, they continued the volume and numbering of the Essex Gazette.

Still, circumstances made the New-England Chronicle a new newspaper in the eyes of many readers and renewed the commitment of the printers “to conduct the Business [of printing] in general, and this Paper in particular, in such a Manner as will best promote the public Good.” The Halls proclaimed that it was imperative that they do so “at this important Crisis — when the Property, the LIVES, and (what is infinitely more valuable) the LIBERTY, of the good People of this Country, are in Danger of being torn from them by the cruel Hands of arbitrary Power.” The printers made their editorial perspective clear as they introduced the new New-England Chronicle to the public and solicited subscribers. They hoped to continue providing subscriptions to residents of Salem who had previously supported them, yet they also had an opportunity to expand circulation to new subscribers interested in keeping up with current events, including those who previously read newspapers published in Boston. The Halls published the New-England Chronicle in Cambridge for eleven months, Samuel maintaining the newspaper on his own following Ebenezer’s death in February 1776. The last issue printed in Cambridge appeared on April 4, 1776. Soon after the British evacuated Boston on March 17, 1776, Samuel Hall moved the New-England Chronicle to Boston, dropped the reference to the Essex Gazette in the extended title, and continued the volume and numbering.