What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

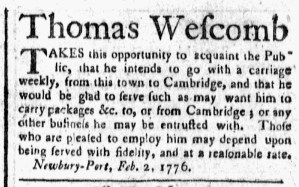

“He intends to go with a carriage weekly, from this town to Cambridge.”

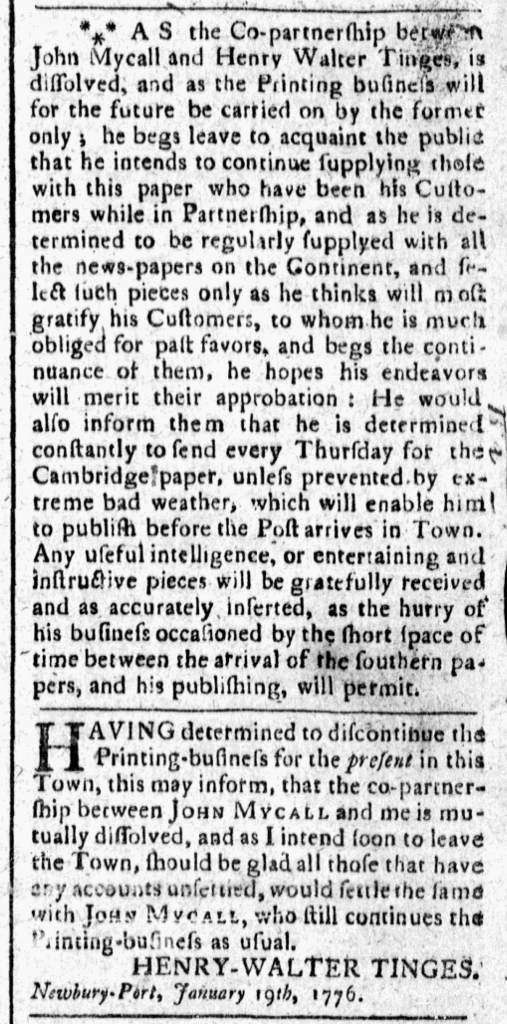

When Thomas Wescomb of Newburyport, Massachusetts, launched a new enterprise, he placed an advertisement in the February 2, 1776, edition of the Essex Journal to promote it to prospective customers. He described his notice as an “opportunity to acquaint the Public, that he intends to go with a carriage, weekly, from this town to Cambridge.” Presumably he took passengers, but he did not provide the rates he charged, describe any of the amenities they could expect, or give further details about the schedule. Other entrepreneurs who advertised carriage or stagecoach service between towns frequently included that kind of information to entice customers. Just a few days earlier, for instance, John Mercereau ran an advertisement for the “New STAGE COACHES, THAT constantly ply between New-York and Philadelphia” in the January 29 edition of the New-York-Gazette and Weekly Mercury. It included a schedule and prices per passenger “in the Coach” and “out” on seats exposed to the weather. He also advised that a second service, called “The Flying Machine” for its speed, “Still continues … from Powles-Hook Ferry, opposite New-York, and from the Sign of the Cross-Keys in Philadelphia.” Mercereau had years of experience operating and advertising his stagecoaches, with advertisements going back as far as 1769.

While Wescomb’s advertisement was not as elaborate or sophisticated, he did pitch other services that he offered, declaring that he “would be glad to serve such as may want him to carry packages” and other items “to, or from Cambridge; or any other business he may be entrusted with.” Notably, Wescomb’s route terminated at Cambridge, not Boston. The Continental Army’s siege of Boston continued, making Cambridge a more significant site than it had been before the Revolutionary War began. Samuel Hall and Ebenezer Hall relocated the Essex Gazette from Salem to Cambridge and renamed it the New-England Chronicle. George Washington, appointed commander-in-chief of the Continental Army by the Second Continental Congress, had his headquarters in Cambridge. Readers of the Essex Journal in Newburyport and other nearby towns likely had a variety of reasons to visit Cambridge or to send packages to officers, soldiers, and others in that town. Wescomb pledged his “fidelity” in delivering those packages or undertaking any other business assigned to him in his efforts to drum up business for his new venture.