What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

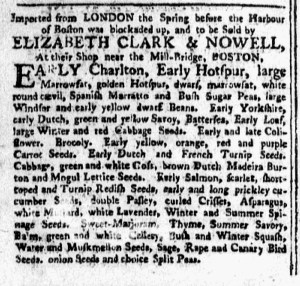

“Imported from LONDON the Spring before the Harbour of Boston was blockade up.”

Although marketing began a little later in the season than in recent years, several retailers placed advertisements for garden seeds in Boston’s newspaper in early March 1775. The March 9 edition of the Massachusetts Spy, for instance, once again carried Susannah Renken’s advertisement as well notices placed by John Adams, Elizabeth Clark and Elizabeth Nowell, and Ebenezer Oliver. Each of these purveyors of seeds took to the public prints as spring approached each year, though many familiar names did not yet appear. More than half a dozen women usually advertised garden seeds that they sold in Boston, but the imperial crisis, especially the closing of the harbor because of the Boston Port Act, disrupted that annual ritual.

Renken, one of the most enterprising of those female seed sellers, apparently acquired her inventory from a ship that landed at Salem. She identified the captain of the vessel that had transported them across the Atlantic. Adams and Oliver both declared that they sold seeds “Imported from London,” but did not provide additional details to allow prospective customers in the eighteenth century (or historians in the twenty-first century) to reach conclusions about when and how they came into possession of those seeds. Clark and Nowell, on the other hand, made clear that their seeds had been “Imported from LONDON the Spring before the Harbour of Boston was blockade up.” They received their seeds at least nine months earlier, a factor that may or may not have been an advantage. Adams declared that he “warrants [his seeds] good, and of the last Year’s Growth.” Similarly, Renken described her seeds as “New and warranted of the last Year’s Growth.” Clark and Nowell could not make such claims. Instead, they attempted to leverage the date of delivery as a point in their favor. Although not “new,” their seeds also were not so old that they would not germinate, especially if Clark and Nowell had stored them carefully. They asked prospective customers to take into account the challenges that they all faced due to the blockade, hoping that a sense of mutual support would convince consumers to select their seeds over the ones offered by their competitors.