What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Determined to SELL OFF his large Assortment of GOODS remarkably Cheap.”

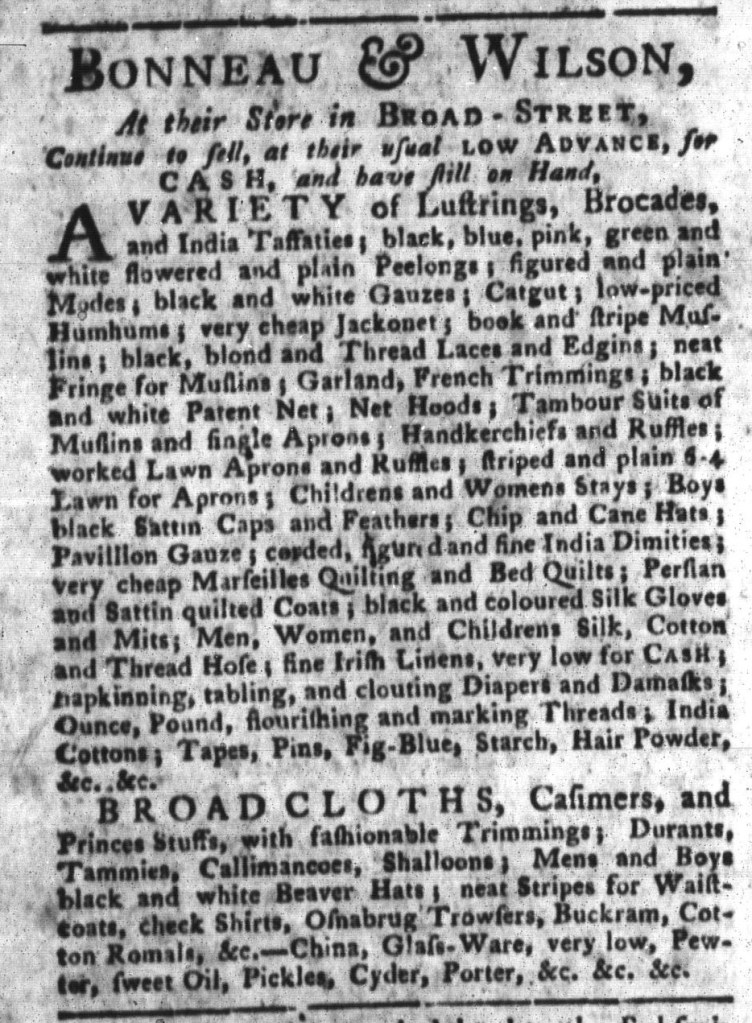

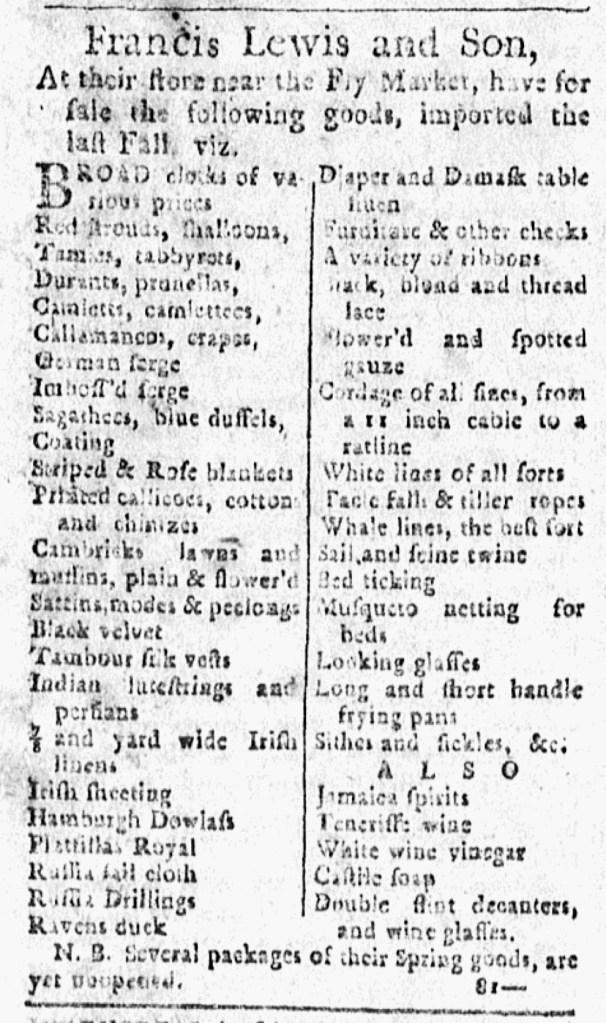

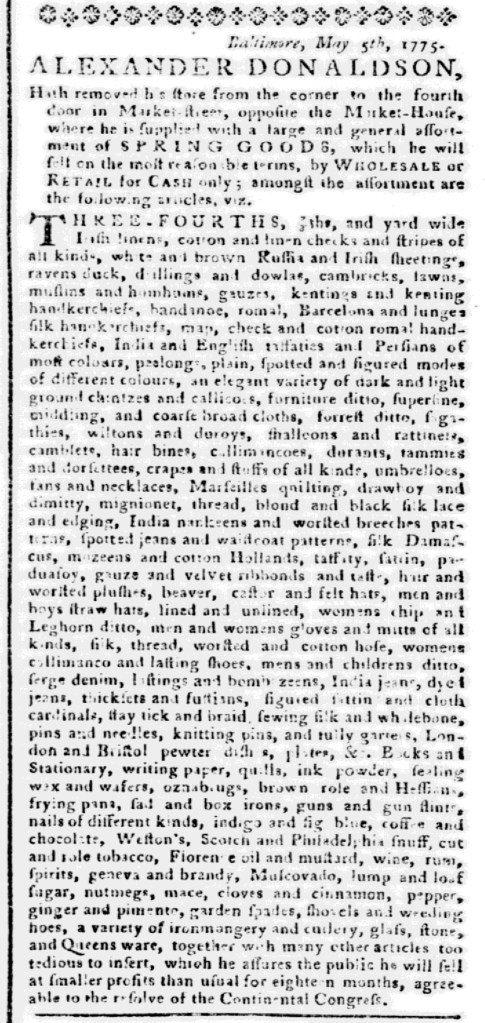

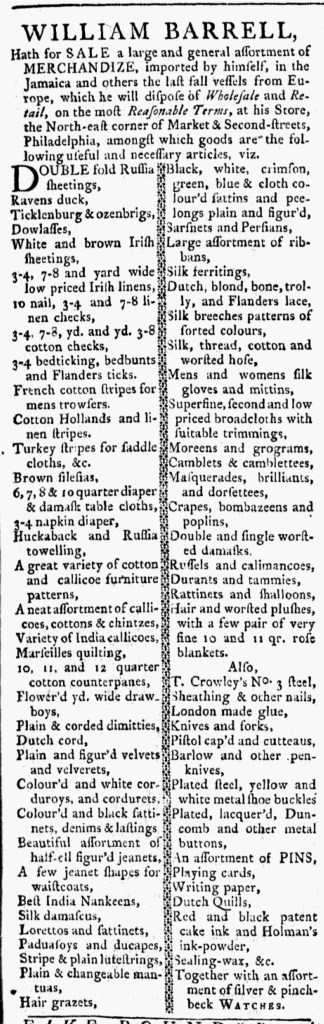

The pages of American newspapers had a different appearance after the Continental Association went into effect on December 1, 1774. While adherence to prior nonimportation agreements had been scattered, this one attracted much greater compliance. As a result, the advertisements that featured lengthy lists of imported merchandise to be sold by local merchants and shopkeepers appeared in the public prints less often, but they did not disappear completely. Notices that listed a few dozen items continued to appear in some newspapers.

Even so, Alexander Bartram’s advertisement for goods “lately imported from the MANUFACTURERS in BRITAIN” seemed extraordinary because of its length. It did not fill only a portion of a column in Story and Humphreys’s Pennsylvania Mercury; instead, it extended an entire column and overflowed into another column. It cataloged dozens of items available at his shop “Next Door to the SIGN of the INDIAN-KING, in MARKET-STREET” in Philadelphia. Dated April 28, Bartram’s advertisement first appeared in the newspaper on that day in 1775 and then again in the supplement the following week. The shopkeeper declared his intention to “SELL OFF his large Assortment of GOODS remarkably Cheap.” He apparently acquired his wares prior to December 1, though he did not make a point of asserting that was the case. The boycott presented an opportunity to clear his shelves of older merchandise since he would not have to compete with new arrivals.

Five months later, his advertisement ran in Story and Humphreys’s Pennsylvania Mercury once again. The compositor had not broken down the type in that time. With the Continental Association still in effect, Bartram saw another opportunity to clear the shelves in his shop … but how many of the items listed in his advertisement remained after his prior attempts to sell them “remarkably Cheap” over the summer? That likely mattered little to Bartram, especially if he believed that such an extensive list would get customers looking for bargains through the doors. A month later, he took to the Pennsylvania Journal with a much shorter advertisement that promoted a “General assortment of MERCHANDIZE, suitable for the season.” Dated October 25 and scheduled to run for six weeks, that notice advised that Bartram “proposes to leave the city in a short time.” If he already planned to depart Philadelphia at the time he republished his lengthy advertisement in late September, he may have considered it worth the expense of taking up so much column space if it might result in significant sales to liquidate his merchandise.