What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

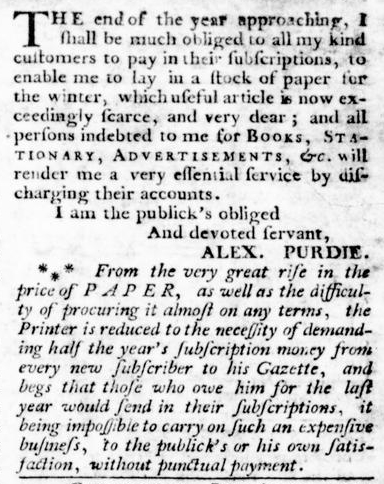

“All persons indebted to me for BOOKS, STATIONARY, ADVERTISEMENTS …”

As 1775 drew to a close, Alexander Purdie placed a notice in his own Virginia Gazette to tend to the business of running that newspaper. A year earlier, he and his former partner, John Dixon, ended their partnership. Dixon took a new partner, William Hunter, and continued printing the Virginia Gazette that he and Purdie had produced together for the last nine years. Purdie immediately announced that he would commence printing a newspaper, that one also named the Virginia Gazette. John Pinkney printed a third Virginia Gazette in Williamsburg.

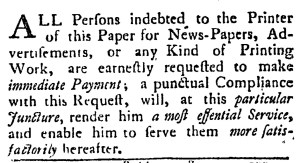

Purdie’s experience and reputation apparently earned him enough customers to make his Virginia Gazette a viable enterprise, though he had to call on them to do their part by paying for the goods and services they purchased on credit. “The end of the year approaching,” the printer explained, “I shall be much obliged to all my kind customers to pay in their subscriptions, to enable me to lay in a stock of paper for the winter, which useful article is now exceedingly scarce, and very dear.” A variety of factors contributed to the scarcity of paper, including disruptions in trade with England due to the Continental Association and the outbreak of hostilities at Lexington and Concord in April.

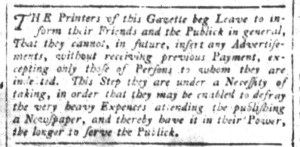

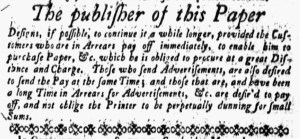

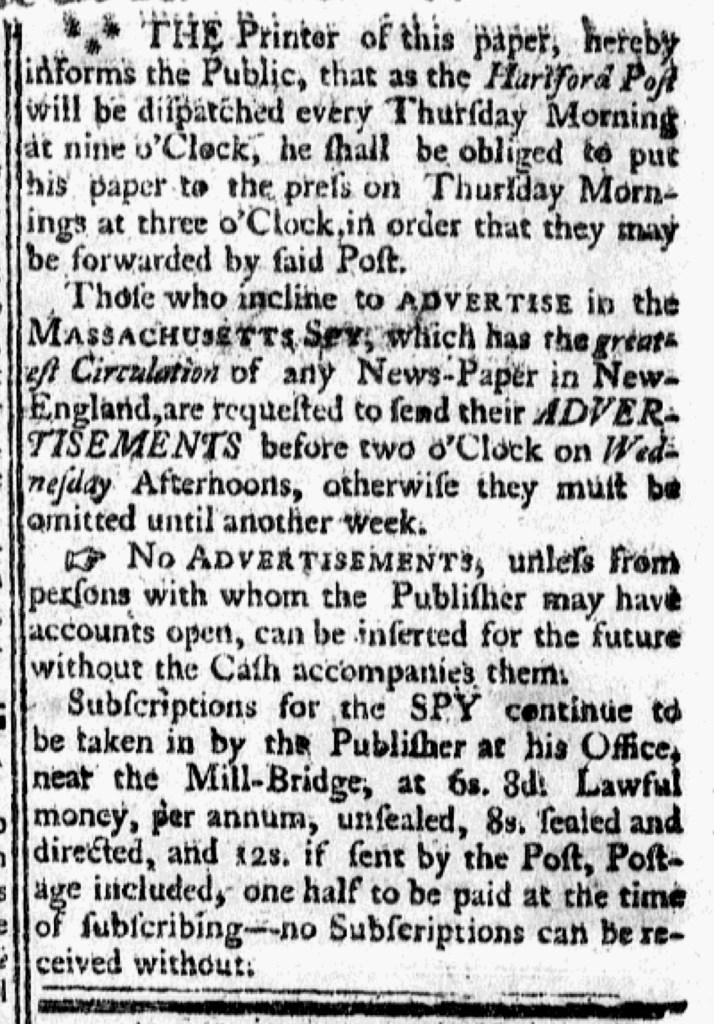

Purdie did not call on subscribers alone to settle accounts. Instead, he declared that “all persons indebted to me for BOOKS, STATIONARY, ADVERTISEMENTS, &c. will render me a very essential service by discharging their accounts.” Yet, he placed the greatest emphasis on subscribers, adding a note that underscored the price and scarcity of paper. “From the very great rise in the price of PAPER, as well as the difficulty of procuring it almost on any terms,” he proclaimed, “the Printer is reduced to the necessity of demanding half the year’s subscription money from every new subscriber to his Gazette.” Such instructions deviated from the standard narrative about how early American printers ran their businesses.

Historians have often asserted that printers extended credit for subscriptions while requiring advertisers to pay in advance, recognizing advertising as the more significant revenue stream. Throughout the colonies, many printers did frequent place notices asking, cajoling, and even threatening legal action in their effort to get subscribers to pay. However, many also specified that subscribers were supposed to pay for half the year “upon entering.” Difficult times forced Purdie to make that a condition for new subscribers. He also seems to have extended credit for advertisements, though his notice did not make clear whether he meant newspaper notices or job printing (like handbills and broadsides) or both. Even as printers followed standard practices, how they actually applied them varied from printing office to printing office.