What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

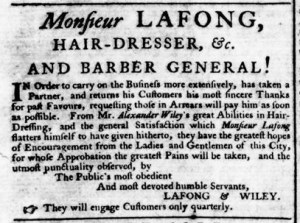

“Monsieur LAFONG, HAIR-DRESSER, &c. AND BARBER GENERAL!”

George Lafong, a “French HAIR-DRESSER” in Williamsburg, occasionally placed newspaper advertisements in the early 1770s. When he took to the pages of the first issue of John Dixon and William Hunter’s Virginia Gazette for 1776, he presented himself as “Monsieur LAFONG, HAIR-DRESSER, &c. AND BARBER GENERAL!” That elaborate and spectacular title served as the headline for his advertisement. He had not previously dropped his first name in favor of referring to himself as “Monsieur LAFONG,” but apparently decided that circumstances merited this affectation.

That may have been because he jointly placed the advertisement with his new partner, Alexander Wiley, explaining that they went into business together “IN Order to carry on the business more extensively.” Wiley possessed “great Abilities in Hair-Dressing,” according to the advertisement, yet neither his name nor reputation seemed to suggest any connection to French styles. Hairdressers frequently benefited from the cachet that their clientele associated with French fashion, something that Lafong understood when he introduced himself as a “French HAIR-DRESSER” and there in a French phrase, “TOUT A LA MODE,” in 1770. He doubled down on that in his new advertisement, naming himself “Monsieur Lafong” in the body as well as “Monsieur LAFONG” in the headline.

The new partners hoped that the combination of Wiley’s “great Abilities in Hair-Dressing, and the general Satisfaction which Monsieur Lafong flatters himself to have hitherto given” would yield “Encouragement” (or appointments) “from the Ladies and Gentlemen of this City.” Lafong deserved to lean on his reputation. According to the entry on wigmakers from the Williamsburg Craft Series, Lafong operated one of the premiere wig shops in the town in the early 1770s.[1] In his own marketing, he declared that he “makes Head Dresses for Ladies, so natural as not to be distinguished by the most curious Eye.” If former clients (or their acquaintances who knew who dressed their hair) agreed with that assessment, it did indeed suggest a “general Satisfaction” with Lafong’s work. Furthermore, Lafong and Wiley promised that “the greatest Pains will be taken” to earn the approval of their clients.

**********

[1] Thomas K. Bullock and Maurice B. Tinkin, Jr., The Wigmaker in Eighteenth-Century Williamsburg: An Account of his Barbering, Hair-Dressing, and Peruke-Making Services, and Some Remarks on Wigs of Various Styles (Colonial Williamsburg: 1959, 1987).