What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“The said gentlemen have not yet been able to settle with Robert Bell.”

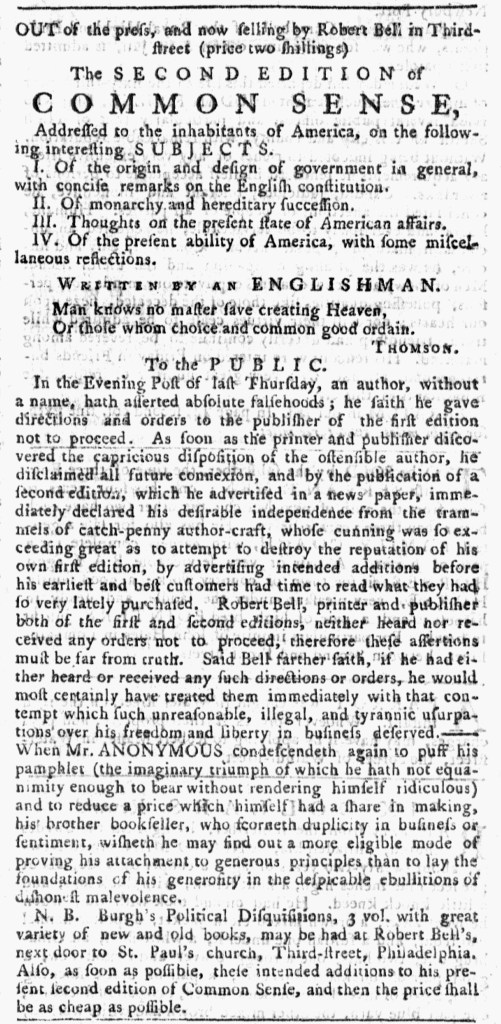

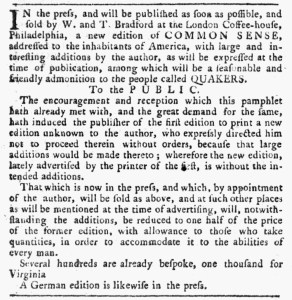

The feud between the Thomas Paine, the author of Common Sense, and Robert Bell, the publisher of the first edition of Common Sense, intensified in the January 30, 1776, edition of the Pennsylvania Evening Post. Advertisements for Bell’s unauthorized “SECOND EDITION” and a “NEW EDITION” currently “In the press, and [to] be published as soon as possible” by William Bradford and Thomas Bradford dominated the final page of that newspaper. Variations of both advertisements appeared in the Pennsylvania Evening Post three days earlier, each of them stirring the pot and inspiring Bell and Paine to submit new material to Benjamin Towne, the printer of that newspaper, to incorporate into their advertisements.

The advertisement for the Bradfords’ edition still included an address “To the PUBLIC,” but it doubled in length with a “declaration” made by the author “for the sake of relieving the anxiety of his friends.” At this point, Paine remained anonymous, at least as far as associating his name with the political pamphlet in the public prints was concerned. He explained that his original plan for Common Sense had been to have it “printed in a series of newspapers,” but others, including Benjamin Rush, convinced him that was impractical and that even printers who supported the American cause would shy away from such radical content. Rush recommended Robert Bell, the noted bookseller as an alternative to the several printers who published newspapers in Philadelphia, acting as an intermediary between Paine and Bell. In this new “declaration,” Paine explained that “he knew nothing of Robert Bell, who was engaged to print it by a gentleman of this city,” referring to Rush but not naming him. Though Rush acted “from a well meaning motive,” his suggestion eventually embroiled Paine in “the unpleasant situation.”

Paine did not hesitate to name Bell, proclaiming that he “hath neither directly, nor indirectly, received, or is to receive, any profit or advantage from the edition printed by Robert Bell.” In the agreement negotiated by Rush, Paine paid for the expense of printing the pamphlet whether it sold or not. In addition, that “noisy man,” Bell, would receive “one half of the profits” if the pamphlet was a success. Paine estimated that amount should have been “upwards of thirty pounds.” Furthermore, the author did not intend to keep his half of the profits. Instead, “when news of our repulse at Quebec arrived in this city,” he committed his share “for the purpose of purchasing mittens for the troops ordered on that cold campaign.” An assault on Quebec City, part of the invasion of Canada undertaken by American forces, had failed on New Year’s Eve. The patriotic Paine wanted to send supplies, especially mittens, to the American soldiers who continued the siege of that city, but Bell did not turn over any money “into the hands of two gentlemen” that Paine designated as his intermediaries. Paine claimed that he had “Bell’s written promise” for that arrangement. Anyone who wished to do so could verify that by consulting with them since their “names are left at the bar of the London Coffee-house” for that purpose.

“The said gentlemen,” Paine continued, “have not yet been able to settle with Robert Bell according to the conditions of his written engagement.” In addition, when they examined his account of the expenses and sales, they did not consider it “equitable” according to that agreement. Paine warned that Bell had a week to make good on their agreement or else “he will be sued for the same.” He concluded by stating, “This is all the notice that will ever be taken of him in future.” Given the ferocity of the advertisements already published, readers may have doubted that.

The advertisement for the Bradfords’ edition featured far more new material than Bell’s advertisement. He added a few lines to the nota bene that ran in the previous edition of the Pennsylvania Evening Post, though he had been so anxious to publish his updated advertisement that he inserted it in the January 29 edition of Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packetrather than waiting for it to appear in the Pennsylvania Evening Post on January 30. In Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet, Bell’s expanded advertisement ran next to the shorter version of the advertisement for the Bradfords’ edition of Common Sense, the one that included an address “TO THE PUBLIC” but not the additional “declaration” by the author.

Bell took the opportunity to demean the “NEW EDITION” the Bradfords were printing. He declared that “the public may be certain” that the “smallness of print and scantiness of paper” meant that it would be an inferior edition “when compared with Bell’s second edition.” Why would readers wait for the Bradfords’ edition “yet in the press” when Bell’s second edition was “out of the press” and available for sale? As a final insult, he trumpeted that comparing the Bradfords’ forthcoming edition to his own second edition was like the difference “in size and value” between a “British shilling” and a “British half-crown.” His second edition, Bell claimed, was the better value in so many ways. Even though Paine pledged that he had nothing more to say about Bell, that made it seem unlikely that the author and the publisher of the first edition would quietly discontinue their attacks in the public prints. In three short weeks since the first advertisement for Common Sense appeared in the Pennsylvania Evening Post, the controversy between Bell and Paine became its own commotion!