What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

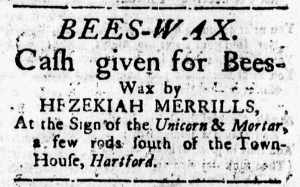

“At the Sign of the Unicorn and Mortar … the best and freshest drugs and medicines.”

An unsigned advertisement in the September 7, 1775, edition of the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter promoted “ALL kinds of the best and freshest drugs and medicines” available “At the Sign of the Unicorn and Mortar in Marlborough Street.” Silvester Gardiner advertised “Drugs and Medicines, both Chymical and Galenical,” and “Doctor’s Boxes” and “Surgeon’s Chests” for ships that he sold “at the Sign of the Unicorn and Mortar inMarlborough-Street” in the Boston Evening-Post as early as June 18, 1744. He continued running advertisements that featured both his name and his shop sign for seven years, but by the middle of the 1750s advertisements that directed prospective customers to the Unicorn and Mortar no longer included the name of the proprietor. Perhaps Gardiner believed that his name had become synonymous with the image that branded his shop. If so, he may have been the apothecary who placed the advertisement in the fall of 1775. On the other hand, another entrepreneur may have acquired the shop and the sign at some point and determined that it made good business sense to continue selling medicines at a familiar location marked with a familiar image.

The Unicorn and Mortar was a popular device among apothecaries in colonial America. Just as Boston had a shop “At the Sign of the Unicorn and Mortar,” so did Hartford, New York, Philadelphia, Providence, and Salem. The partnership of Gardiner and Jepson sold a “complete Assortment” of medicines “at the Sign of the Unicorn and Mortar, in Queen-Street, HARTFORD,” according to advertisements in the May 5, 1759, edition of the Connecticut Gazette, published in New Haven, and the March 21, 1760, edition of the New-London Summary. Hartford did not have its own newspaper until 1764, so Gardiner and Jepson resorted to newspapers published in other towns to encourage the public to associate the Unicorn and Mortar with their business. The experienced Silvester Gardiner may have taken William Jepson as a junior partner to run the shop in Hartford. A few years later, Jepson, “Surgeon and Apothecary, at the Unicorn and Mortar, in Queen Street, Hartford,” ran advertisements on his own, starting with the December 21, 1767, edition of the Connecticut Courant. Within a decade, Hezekiah Merrill, “APOTHECARY and BOOKSELLER,” advertised his own shop “at the Sign of the Unicorn and Mortar, a few Rods South of the Court-House in Hartford.” He ran a full-page advertisement in the December 21, 1773, edition of the Connecticut Courant and many less extensive advertisements in other issues. When Merrill opened his “New STORE” he did not refer to it as the Unicorn and Mortar. Perhaps he eventually acquired the sign from Jepson, whose advertisements no longer appeared, and hoped to leverage the familiar image at a new location. Residents of Hartford recognized the Unicorn and Mortar and associated it with medicines no matter who ran the shop, whether Gardiner and Jepson, Jepson alone, or Merrill.

Apothecaries in other towns also marked their locations with the Unicorn and Mortar. Patrick Carryl announced that he moved “to the Sign of the Unicorn and Mortar” in the May 23, 1748, edition of the New-York Gazette. He ran advertisements for more than a decade, always associating his name with his shop sign. John Prince ran an advertisement in the February 6, 1764, edition of the Boston Post-Boy to announce that “he has lately Opened his Shop at the Sign of the Unicorn and Mortar, near the Town-House in Salem.” John Sparhawk operated his own apothecary shop “At the Unicorn and Mortar, in Market-Street, near the Coffee-House,” in Philadelphia, according to his advertisement in the December 18, 1766, edition of the Pennsylvania Gazette. By the time he advertised in the Pennsylvania Chronicle on March 4, 1771, he gave the full name as the “London Book-store, and Unicorn and Mortar.” In that notice and others, he promoted a “NEAT edition of TISSOT’s Advice to the People respecting their Health” in addition to “Drugs and Medicines of all kinds as usual.” Building his brand, Sparhawk placed many newspaper advertisements that mentioned the Unicorn and Mortar over the course of several years. Benjamin Bowen and Benjamin Stelle sold “MEDICINES … at the well-known Apothecary’s Shop … at the Sign of the Unicorn and Mortar,” according to their advertisement in the August 25, 1770, edition of the Providence Gazette. Apothecaries in other towns likely marked their locations with a sign depicting the Unicorn and Mortar. It became a familiar emblem that consumers easily recognized by the time that the anonymous advertiser ran a notice in the Massachusetts Gazette and Boston Weekly News-Letter in the fall of 1775.