What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“… that we may not now, nor hereafter, have any occasion to import from our ministerial enemies in Great-Britain.”

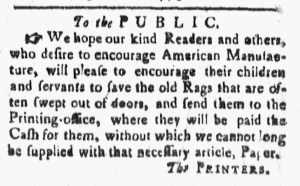

Charles Maise, a “MUSTARD and CHOCOLATE MAKER” in Philadelphia, took to the pages of Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet to promote his business at the end of July 1775. First, he needed supplies, offering “Forty shillings per bushel for any quantity of good clean Mustard-seed.” Yet Maise wanted readers to think bigger about his business and their role as both suppliers and consumers given the imperial crisis experienced in the colonies over the last decade. He expressed his hope that “farmers and others will use their best endeavours to encourage this valuable manufactory, by cultivating and improving the growth of so valuable an article, that we may not now, nor hereafter, have any occasion to import from our ministerial enemies in Great-Britain.” Such sentiments certainly resonated with the Continental Association, a nonimportant agreement devised by the First Continental Congress in the fall of 1774 in response to the Coercive Acts. The eight article called on colonizers “in our several Stations,” including mustard and chocolate makers, to “encourage Frugality, Economy, and Industry; and promote Agriculture, Arts, and the Manufactures of this Country.”

Producers had a part to play in making available alternatives to imported goods, but the Continental Association did not depend on their efforts alone. Consumers also had to make choices aligned with their political principles. That meant purchasing “domestic manufactures,” goods produced in the colonies. Maise stood ready to partner with consumers in pursuing their common cause. In a nota bene, he announced that he “stands in the market on market days, opposite the London Coffee-house.” Customers could find him there. He extended “thanks to his former customers,” stating that he “hopes for a continuance of their favours, and doubts not but to merit their esteem.” Of course, Maise also intended for his advertisement to reach new customers and wanted them to join existing customers in supporting both his business and the American cause by purchasing mustard produced locally from mustard seeds grown in the colonies. Mustard gained political significance when taking into consideration “our ministerial enemies in Great-Britain,” especially in the wake of recent news of hostilities commencing at Lexington and Concord, the siege of Boston, and the Battle of Bunker Hill.