What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

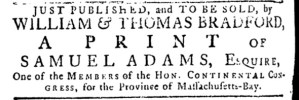

“A PRINT OF SAMUEL ADAMS, ESQUIRE, One of the MEMBERS of the HON. CONTINENTAL CONGRESS.”

The Second Continental Congress convened in Philadelphia after the battles of Lexington and Concord. It met through most of the summer of 1775, took a recess during August, and started meeting again in September. The delegates had just resumed their deliberations when William Bradford and Thomas Bradford, the printers of the Pennsylvania Journal, ran an advertisement promoting “A PRINT OF SAMUEL ADAMS, ESQUIRE, One of the MEMBERS of the HON. CONTINENTAL CONGRESS, for the Province of Massachusetts-Bay.”

Even though their advertisement stated, “JUST PUBLISHED, and TO BE SOLD, by WILLIAM & THOMAS BRADFORD,” this seems to have been another instance of printers treating those two phrases separately. “TO BE SOLD” did indeed refer to the Bradfords stocking and selling the print at their printing office, but “JUST PUBLISHED” did not indicate that they had published the published the print, only that someone had recently published it and made it available for sale. The Bradfords did not previously attempt to incite demand or gauge interest in a print of Adams among residents of Philadelphia with a subscription notice or other advertisement.

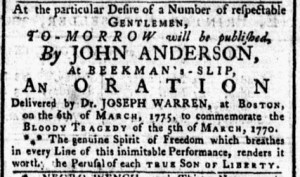

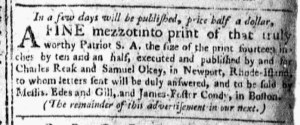

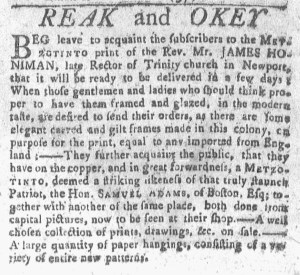

They most likely acquired and sold copies of the print that Charles Reak and Samuel Okey advertised in the Newport Mercury, the Massachusetts Spy, and the Boston-Gazette several months earlier. In February, Reak and Okey took to the pages of the Newport Mercury to announce their intention to print a “striking likeness of that truly staunch Patriot, the Hon, SAMUEL ADAMS, of Boston.” Near the end of March, a truncated advertisement in the Massachusetts Spy and the Boston-Gazette advised that “[i]n a few days will be published … A FINE mezzotinto print of that truly worthy Patriot S. A. … executed and published by and for Charles Reak and Samuel Okey, in Newport, Rhode-Island.” The version in the Massachusetts Spy indicated that more information would appear in the next issue, but the printer, Isaiah Thomas, did not supply additional details in the last few issues printed in Boston before he suspended the newspaper for several weeks and relocated to Worcester just before hostilities commenced at Lexington and Concord. Those events gave Reak and Okey an expanded market for a print of a Patriot leader already famous in New England. Their advertisements in Boston’s newspapers listed local agents who would sell their print there. The Bradfords likely became local agents in Philadelphia rather than publishers of another print of Adams.