GUEST CURATOR: Michael “OB” O’Brien

What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“Rattinets and buttons; shalloons and durants.”

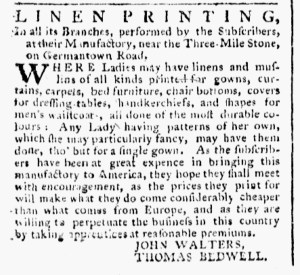

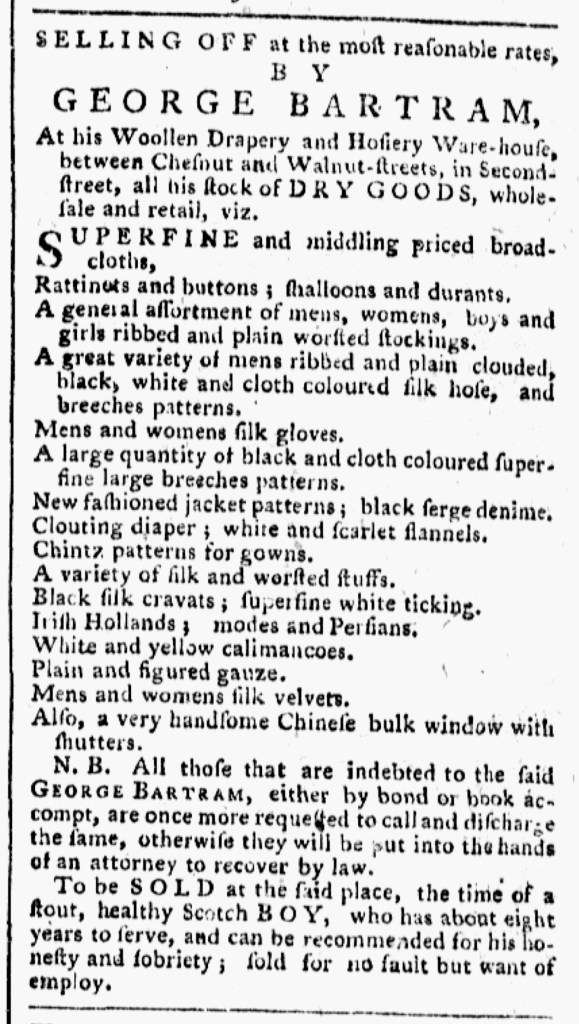

When I first examined George Bartram’s advertisement in the Pennsylvania Packet on February 19, 1776, I noticed how crowded it was with imported fabrics and fashionable goods. Bartram listed “New fashioned jacket patterns,” a “general assortment of mens, womens, boys and girls ribbed and plain worsted stockings,” silk gloves, and numerous types of cloth (such as rattinets, shalloons, and durants), all meant to appeal to customers looking for style and choice. His shop offered more than just the necessities. He encouraged customers to browse, compare, and imagine new possibilities of how they might dress. In The Marketplace of Revolution: How Consumer Politics Shaped American Independence, T.H. Breen states that “as the index of choice expanded, so too the dreams of possession flourished.”[1] Bartram’s advertisement reflected exactly that expanding world of choice. The abundance of fabrics and fashionable goods available in his Philadelphia shop shows how deeply colonists participated in the marketplace even on the brink of the American Revolution.

**********

ADDITIONAL COMMENTARY: Carl Robert Keyes

Nearly a year after George Bartram announced in the Pennsylvania Evening Post that he “resolved to decline his Retail Trade,” he once again ran an advertisement about “SELLING OFF” the inventory at his “Woollen Drapery and Hosiery Ware-house” in Philadelphia. He offered his wares “wholesale and retail,” indicating that he had neither gone out of business nor became a merchant who dealt solely in wholesale transactions. As Michael notes, Bartram stocked a wide array of imported goods. He conveniently did not mention whether his merchandise arrived in Philadelphia before the Continental Association went into effect.

By the time he ran his advertisement in February 1776, Bartram’s warehouse on Second Street between Chestnut Street and Walnut Street was a landmark familiar to residents of Philadelphia. In 1767, he opened his “new Shop at the Sign of the Naked Boy.” His advertisements in the Pennsylvania Chronicle featured a woodcut depicting that sign. In a cartouche in the center, a naked boy unfurled a length of fabric. Bolts of textile flanked the cartouche with Bartram’s name appearing beneath them. Replicating his shop sign in the public prints likely improved Bartram’s visibility in the busy port city. He continued publishing advertisements with that image for several years.

Yet Bartram eventually abandoned the device that marked his location for so long in favor of rebranding his store as “GEORGE BARTRAM’s WOOLLEN DRAPERY AND HOSIERY WARE-HOUSE, At the Sign of the GOLDEN FLEECE’S HEAD,” though he remained at the same location on Second Street. His new advertisements sometimes featured a woodcut depicting his new device, though on other occasions he opted for no decorative elements or a border comprised of printing ornaments rather than the image of “the Sign of the GOLDEN FLEECE’S HEAD.” His advertisements did not reveal why he opted for a new sign to mark his location and identify his business.

In subsequent advertisements, Bartram proclaimed that he was “SELLING OFF” his inventory and leaving the “Retail Trade.” He made such pronouncements in March 1775 and September 1775, though in the latter he clarified that he would cease retail operations “so soon as the trade is open between Britain and America.” Once the war that started in April 1775 became a revolution, the resumption of trade became even more uncertain. For the moment, Bartram continued “SEELING OFF” his inventory “at the most reasonable rates,” making him a precursor to modern businesses that constantly promote sales to draw customers. The marketing tried to create a sense of urgency by suggesting a limited-time offer, yet savvy consumers likely realized that one sale followed another at Bartram’s “Woollen Drapery and Hosiery Ware-house.”

**********

[1] T.H. Breen, The Marketplace of Revolution: How Consumer Politics Shaped American Independence (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 58.