What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

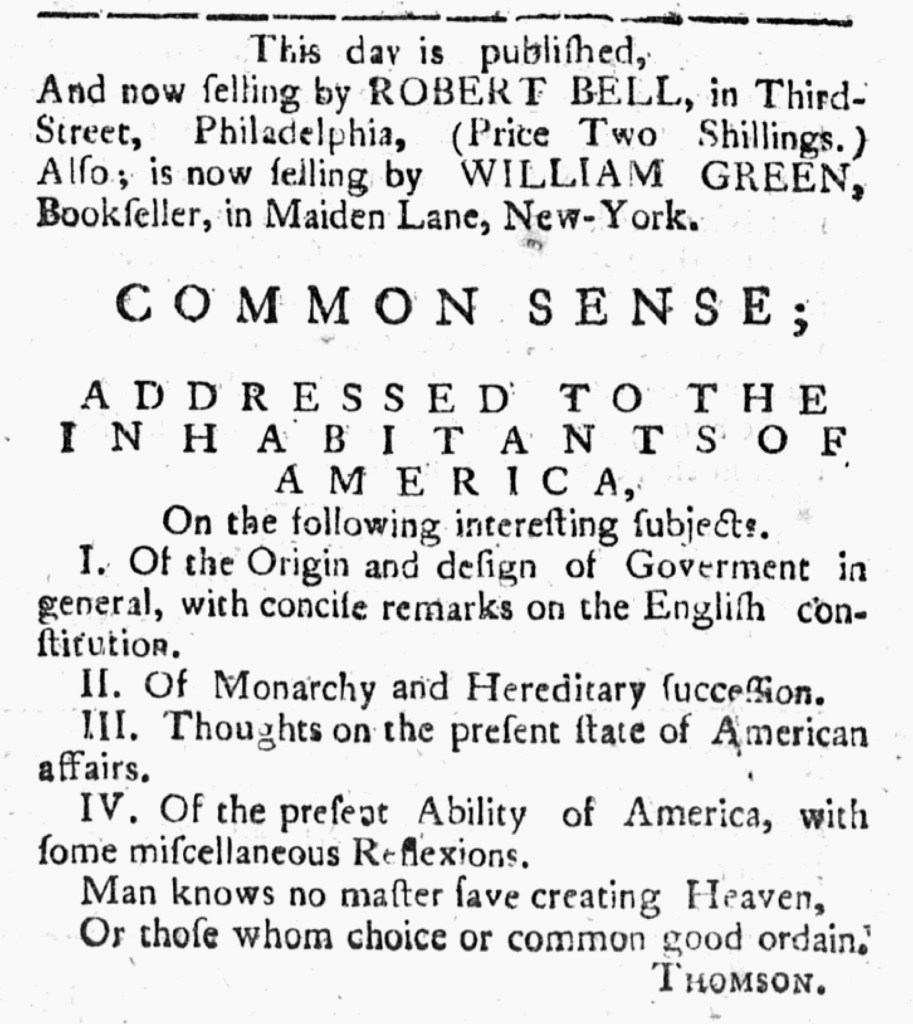

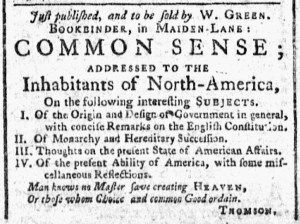

“To be sold by W. GREEN … COMMON SENSE.”

Just days after an advertisement for Thomas Paine’s Common Sense made its first appearance in a newspaper beyond those published in Philadelphia, a second advertisement appeared in yet another newspaper. The Constitutional Gazettecarried that first advertisement on January 20, 1776. A variation ran in the New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury on January 22.

Both advertisements included the title of the political pamphlet, “COMMON SENSE,” though the version in the Constitutional Gazette indicated that it was “ADDRESS TO THE INHABITANTS OF AMERICA” while the one in the New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury instead stated that it was “ADDRESSED TO THE Inhabitants of North-America.” Both listed the “interesting SUBJECTS” contained within the pamphlet, offering four section headings that included “Of the Origin and Design of Government in general, with concise Remarks on the English Constitution” and “Thoughts on the present State of American Affairs.” Both concluded with an epigraph from James Thomson’s poem, “Liberty” (1734): “Man knows no Master save creating HEAVEN, / Or those whom Choice and common Good ordain.” Those lines previewed the arguments readers would encounter in the pamphlet. These advertisements in newspapers printed in New York replicated those previously published in newspapers in Philadelphia.

The new advertisement in the New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury did have one significant difference from the earlier advertisements. It did not include the name of the publisher of the first edition, Robert Bell. The introduction to the version in the Constitutional Gazette did mention the prominent printer and bookseller, advising readers that “ROBERT BELL, in Third-Street, Philadelphia,” sold the pamphlet and then also listing William Green, a “Bookseller, in Maiden Lane, New-York,” as a local purveyor of Common Sense. The version in the New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury, however, eliminated Bell and named Green as the sole vendor of the pamphlet: “Just published, and to be sold by W. GREEN. BOOKBINDER, in MAIDEN-LANE.” Eighteenth-century readers knew to separate the phrases “Just published” and “to be sold by.” Only the latter referred to Green’s role in the production and distribution of the pamphlet. The phrase “Just published” merely meant “now available.” Green did not print Common Sense, but when he submitted copy for his advertisement to the New-York Gazette and Weekly Mercury’s printing office he privileged his role in making the incendiary new pamphlet available in that city. As the pamphlet gained popularity, John Anderson, the printer of the Constitutional Gazette, published and advertised a local edition (and a second local edition), but for a short time Green was the only retailer in New York hawking the pamphlet in the public prints. His marketing efforts contributed to the stir caused by Paine’s appeal to declare independence rather than continue to seek a redress of grievances within the imperial system.