What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

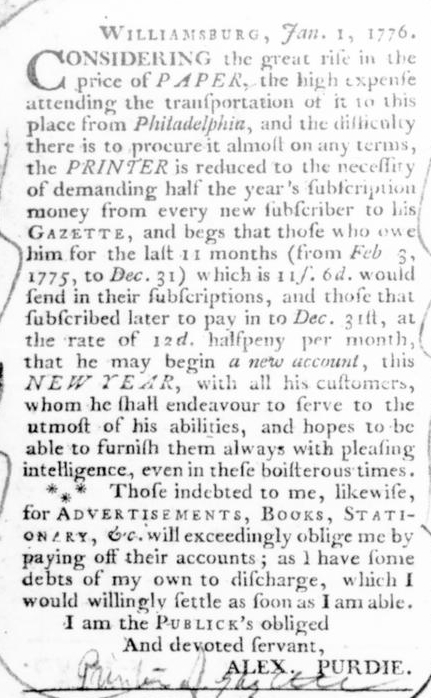

“The PRINTER is reduced to the necessity of demanding half the year’s subscription money.”

In the final issue of his Virginia Gazette for 1775, Alexander Purdie called on subscribers “to pay in their subscriptions, to enable me to lay in a stock of paper for the winter,” and “all persons indebted to me for BOOKS, STATIONARY, [and] ADVERTISEMENTS” to settle their accounts. He asserted that it was “impossible to carry on such an expensive business, to the publick’s or his own satisfaction, without punctual payment.”

A week later, Purdie expressed even more alarm in a notice in the first edition of his Virginia Gazette for 1776. “CONSIDERING the great rise in the price of PAPER, the high expense attending the transportation of it to this place from Philadelphia, and the difficulty there is to procure it almost on any terms,” he explained, “the PRINTER is reduced to the necessity of demanding half the year’s subscription money from every new subscriber to his GAZETTE.” Newspaper subscribers often enjoyed generous credit, but Purdie made clear that was not a viable option. He simultaneously renewed his call “that those who owe him for the last 11 months” since he commenced publication of hisVirginia Gazette “send in their subscriptions” and “those that subscribed later … pay in to Dec. 31st … that he may begin a new account, this NEW YEAR, with all his customers.” Like many other printers, Purdie believed that he performed a valuable service for the public, “hop[ing] to be able to furnish them always with pleasing intelligence, even in these boisterous times.” Many readers may have considered “boisterous” an understatement as they read news and editorials about the war that commenced at Lexington and Concord the previous April.

Where Purdie placed his advertisement within the issue testifies to its urgency. Like other newspapers of the era, his Virginia Gazette consisted of four pages printed on a broadsheet and folded in half. Printers usually printed the first and fourth pages on one side, let it dry, and then printed the second and third pages on the other side. That meant that the news and advertisements that arrived in the printing office most recently appeared on the second and third pages, inside the folded newspaper. Purdie’s Virginia Gazette had a heading for “ADVERTISEMENTS” in the final column of the third page. He could have followed the example of other printers and given his notice a privileged place as the first item under that heading. Instead, he made it the first item in the first column on the fourth page. He placed his notice in the upper left corner of the final page, making it the first advertisement readers encountered then they turned to that page. That also guaranteed a spot for the printer’s notice. Purdie made it a priority rather than risking that news he had not yet received would be of such significance to justify crowding out his notice. Purdie made a savvy decision in choosing where to place his notice calling on subscribers and other customers to settle accounts.