What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

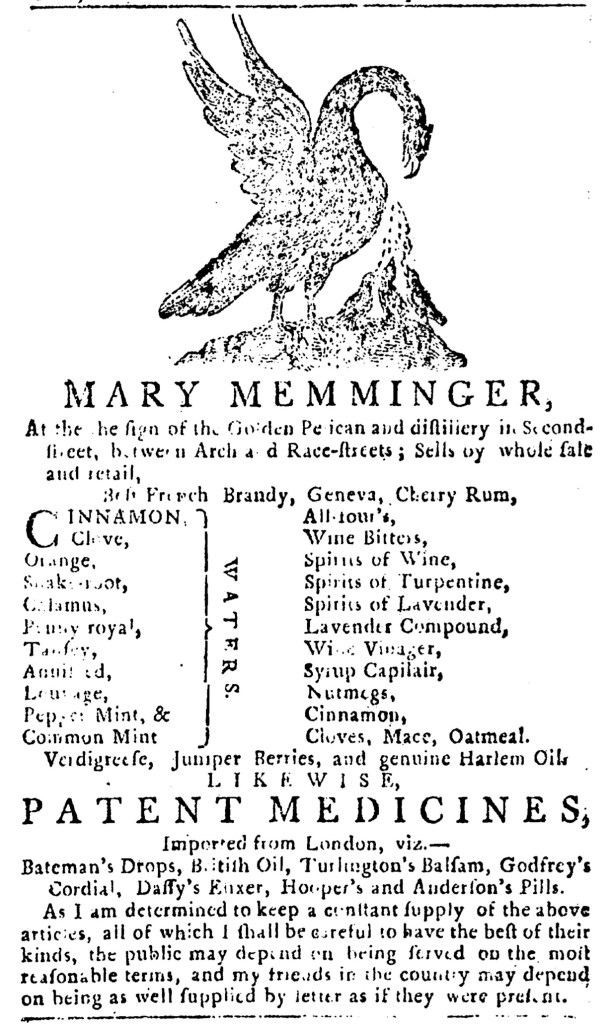

“MARY MEMMINGER, At the sign of the Golden Pelican.”

In the final issue of the Pennsylvania Journal published in 1775 and continuing in January 1776, Mary Memminger advertised the remedies available at her apothecary shop “At the sign of the Golden Pelican” on Second Street in Philadelphia. Memminger described her shop as a “distillery,” suggesting that she may have produced some of the “WATERS” (including cinnamon, clove, orange, peppermint, and “Common Mint”) and “Spirits of Wine,” “Spirits of Turpentine,” and “Spirits of Lavender.” She also stocked popular “PATENT MEDICINES, Imported from London,” listing “Bateman’s Drops, British Oil, Turlington’s Balsam, Godfrey’s Cordial, Daffy’s Elixer, [and] Hooper’s and Anderson’s Pills.” Memminger apparently tended closely to her advertising. The first time her notice appeared, it featured an error, truncating “Godrey’s Cordial, Daffy’s Elixer” to “Godfrey’s Elixer.” The compositor fixed the mistake, a rare instance of an updated version of a newspaper advertisement for consumer goods and services after the type had been set.

Memminger did not indicate when she received the patent medicines “Imported from London,” whether they arrived in the colonies before the Continental Association went into effect on December 1, 1774. Apothecaries and others who sold patent medicines often gave assurances that they were “fresh,” recent arrivals that had not lingered on shelves or in storerooms for months, yet Memminger left it to readers to draw their own conclusions. She did assert that she was “determined to keep a constant supply of the above articles, all of which I shall be careful to have the best of their kinds,” perhaps indicating a willingness to make exceptions when it came to certain imported items. Memminger made the health of her clients her priority, promising that “the public may depend on being served on the most reasonable terms, and my friends in the country may depend on being as well supplied by letter as if they were present.” As a symbol of the care she provided, a woodcut dominated her advertisement (and the entire final page of the January 3, 1776, edition of the Pennsylvania Journal). As William H. Helfand explains, it depicted “a pelican piercing her breast to nourish her young.” Perhaps it replicated the “sign of the Golden Pelican” that marked Memminger’s location. While other apothecaries, like Philip Godfrid Kast and Oliver Smith, deployed images that incorporated mortars and pestles, Memminger declined to include a tool of the trade in favor of emphasizing a symbol of motherly care and sacrifice tending to the welfare of others.