What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“A CORRECT MAP … in which may be seen the march of Col. Arnold.”

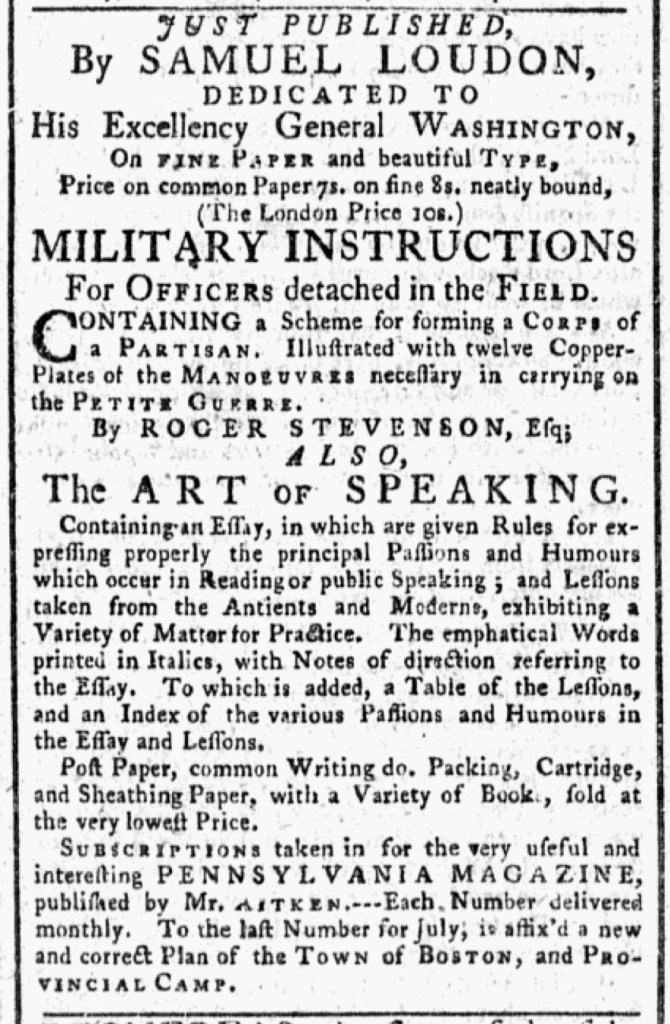

On January 1, 1776, Robert Aitken, a printer and bookseller, advertised that he had for sale a “CORRECT MAP of the great river St. Lawrence, Nova-Scotia, Newfoundland, and that part of New-England, in which may be seen the march of Co. Arnold, from Casco-Bay to Quebec, by wat of Kennebec river.” The map featured insets depicting the “plains of Quebec, the town of Halifax and its harbour, and a small perspective view of the city of Boston.” Like several other maps and prints advertised in the months following the outbreak of hostilities at Lexington and Concord in April 1775, this map supplemented the news that colonizers read in the newspapers and heard when they discussed current events.

This “CORRECT MAP” aided in understanding the dual-pronged American invasion of Quebec that commenced near the end of August. General Richard Montgomery and 1200 soldiers headed from Fort Ticonderoga, New York, recently captured from the British, toward Montreal. That city surrendered to Montogomery on November 13. Meanwhile, Colonel Benedict Arnold and 1100 soldiers sailed from Newburyport, Massachusetts, to the mouth of the Kennebec River on September 15. They made a harrowing trek through the wilderness of northern New England, losing nearly half their number to death or desertion, before reaching Quebec City on November 14. Arnold and his soldiers besieged the city, eventually supported by Montgomery and reinforcements on December 2. The enlistments for many of the American soldiers ended on December 31, prompting Montgomery and Arnold to attack the city during a snowstorm. The weather did not work to their advantage. Montgomery was killed, Arnold wounded, and four hundred American soldiers captured. Arnold assumed command and continued the siege, realizing that British reinforcements would arrive when the St. Lawrence River became navigable again in the spring. When General John Burgoyne arrived in May, Arnold led a retreat to upstate New York. Ultimately, the American invasion of Canada failed.

When they saw Aitken’s advertisement for a “CORRECT MAP … in which may be seen the march of Col. Arnold” in the January 1 edition of Dunlap’s Pennsylvania Packet, they had no way of knowing about the failed attack that occurred the previous day. Supporters of the American cause still hoped that Montgomery and Arnold would capture Quebec City, dealing a significant blow to the British. Along with newspaper coverage, the map chronicled what readers knew about the invasion of Canada, including the hardships endured by Arnold and the soldiers under his command who endured so many hardships in the wilderness of northern New England.

**********

For more information about the Quebec Campaign, see Nathan Wuertenberg’s more comprehensive overview.