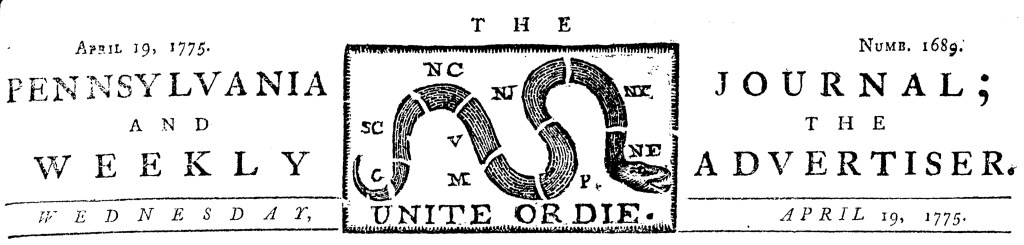

What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

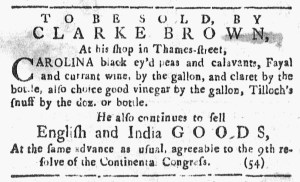

“English and India GOODS, At the same advance as usual, agreeable to the 9th resolve of the Continental Congress.”

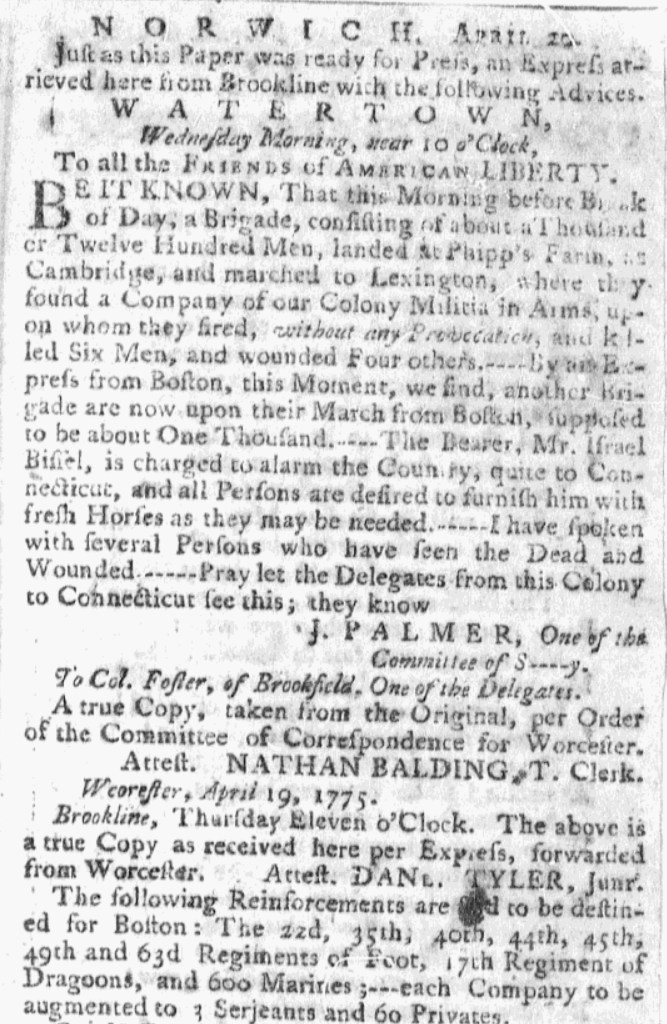

An advertisement that Clarke Brown first placed in the Newport Mercury on January 16, 1775, a little over six weeks after the Continental Association went into effect, ran for several months. It appeared once again on May 1, just two weeks after the battles at Lexington and Concord. In it, Browne promoted several commodities, including peas, wine, and snuff, and advised the public that he “continues to sell English and India GOODS.” He very carefully clarified that he set prices for those imported wares “At the same advance as usual, agreeable to the 9th resolve of the Continental Congress.”

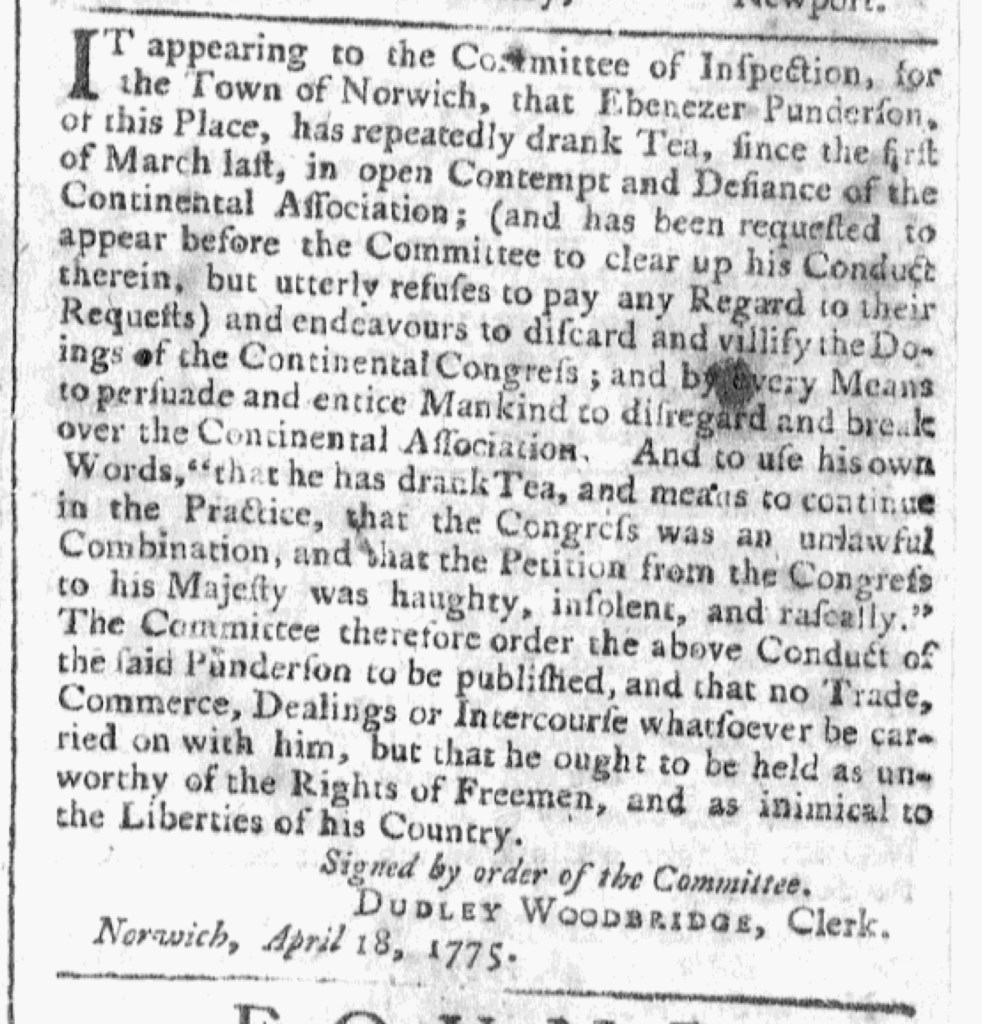

Readers knew that Brown referred to the Continental Association, a nonimportation agreement enacted by the First Continental Congress in response to the Coercive Acts. To prevent price gouging once merchants and shopkeepers ceased importing new inventory from Britain, the ninth article specified that “Venders of Goods or Merchandise will not take Advantage of the Scarcity of Goods that may be occasioned by this Associacion, but will sell the same at the Rates we have been respectively accustomed to do for twelve Months last past.” When Brown declared that he set prices “at the same advance as usual,” he meant that he did not increase the markup but instead held prices steady. He offered assurances to prospective customers. Just as significantly, he wanted readers, whether they shopped at his store or not, to know that he abided by the ninth article of the Continental Association. After all, it specified penalties for those who did not: “if any Venders of Goods or Merchandise shall sell any such Goods on higher Terms … no Person ought, nor will any of us deal with any such Person … at any Time thereafter, for any Commodity whatever.” Brown’s good standing in the community, not just his ability to earn his livelihood, depended on convincing the public that he charged fair prices consistent with the expectations of the Continental Association.