What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“A large and exact VIEW of the late BATTLE at CHARLESTOWN.”

Like other printers, John Dixon and William Hunter sold books, pamphlets, almanacs, stationery, and other merchandise to supplement the revenues they generated from newspaper subscriptions, advertisements, and job printing. They frequently placed advertisements in their newspaper, the Virginia Gazette, to generate demand for those wares. The December 23, 1775, edition, for instance, included three of their advertisements, one for “SONG BOOKS and SCHOOL BOOKS For SALE at this OFFICE” and another for the “Virginia ALMANACK” for 1776 with calculations “Fitting VIRGINIA, MARYLAND, [and] NORTH CAROLINA” by “the ingenious Mr. DAVID RITTENHOUSE of Philadelphia,” the same mathematician who did the calculations for Father Abraham’s Almanack marketed in Philadelphia and Baltimore.

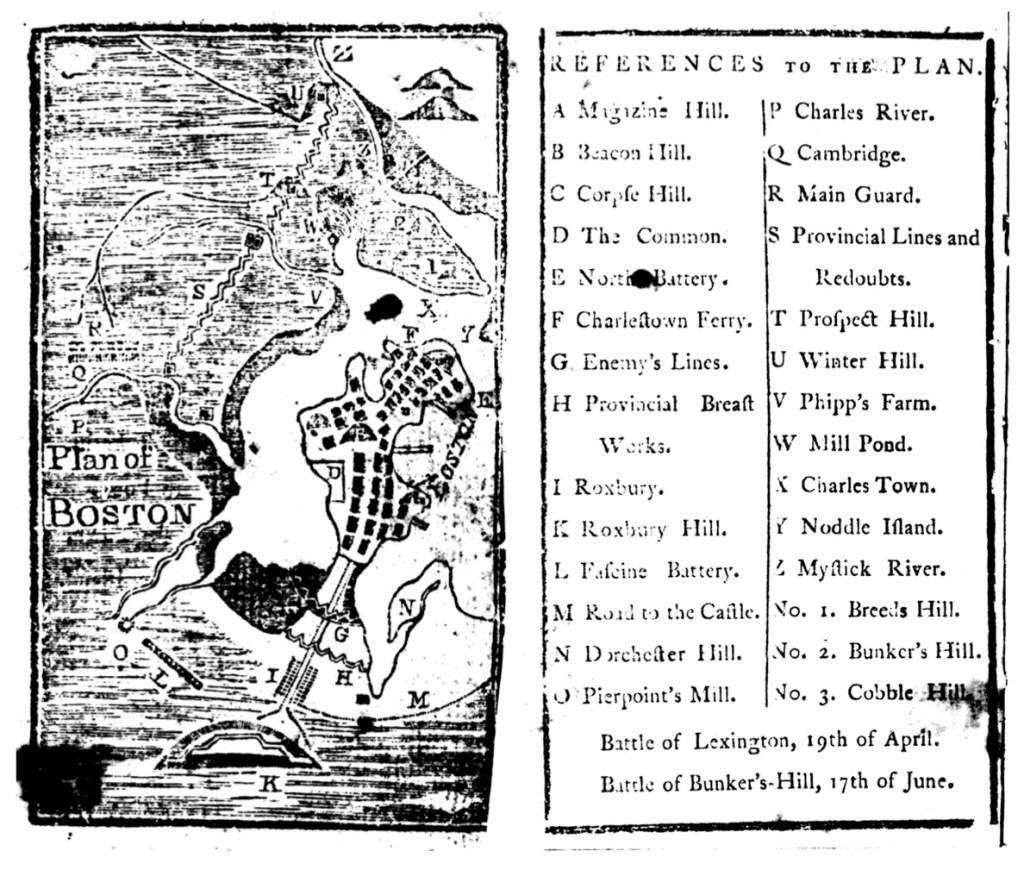

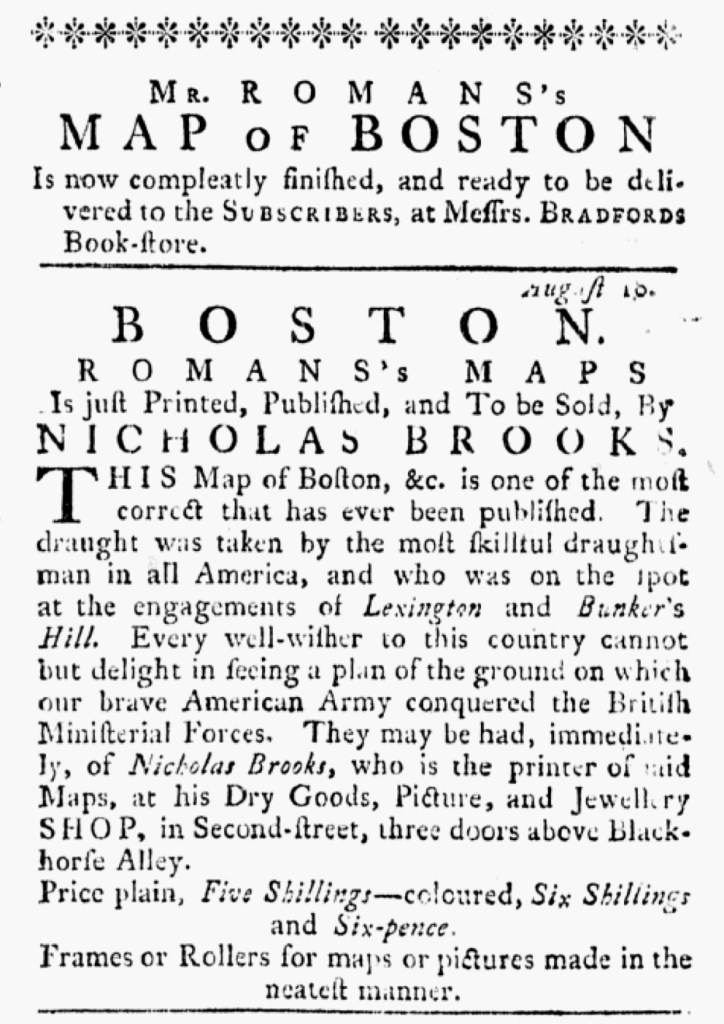

Their third advertisement promoted memorabilia related to the hostilities that erupted at Lexington and Concord earlier in the year. “Just come to Hand, and to be SOLD at this PRINTING-OFFICE,” Dixon and Hunter proclaimed, “A large and exact VIEW of the late BATTLE at CHARLESTOWN,” now known as the Battle of Bunker Hill. The copies they stocked were “Elegantly coloured” and sold for “one Dollar.” Dixon and Hunter apparently carried a print, “An Exact View,” engraved by Bernard Romans and published by Nicholas Brooks, rather than a striking similar (and perhaps pirated) print, “A Correct View,” that Robert Aitken included in a recent issue of the Pennsylvania Magazine, or American Monthly Museum and sold separately. Romans and Brooks had advertised widely and designated local agents to accept subscriptions for the print. Dixon and Hunter also advertised another collaboration between Romans and Brooks, “an accurate MAP of The present SEAT of CIVIL WAR, Taken by an able Draughtsman, who was on the Spot at the late Engagement.” The map also sold for “one Dollar.” Previous efforts to market the map included a broadside subscription proposal that listed local agents in various towns, including “Purdie and Dixon, Williamsburgh.” Romans and Brooks apparently had not consulted with all the printers, booksellers, and other men they named as local agents when they drew up the list or else they would have known that Alexander Purdie and John Dixon had dissolved their partnership in December 1774. Dixon took on Hunter as his new partner while Purdie set about publishing his own Virginia Gazette. Those details may have mattered less to Romans and Brooks than their expectation that printers, booksellers, and others with reputations for supporting the American cause would indeed aid them in marketing and selling a map depicting the conflict underway in Massachusetts. Whether or not Purdie or Dixon and Hunter collected subscriptions, local agents in Williamsburg did eventually sell the print and the map that supplemented newspaper accounts and encouraged feelings of patriotism among the consumers who purchased them.