What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

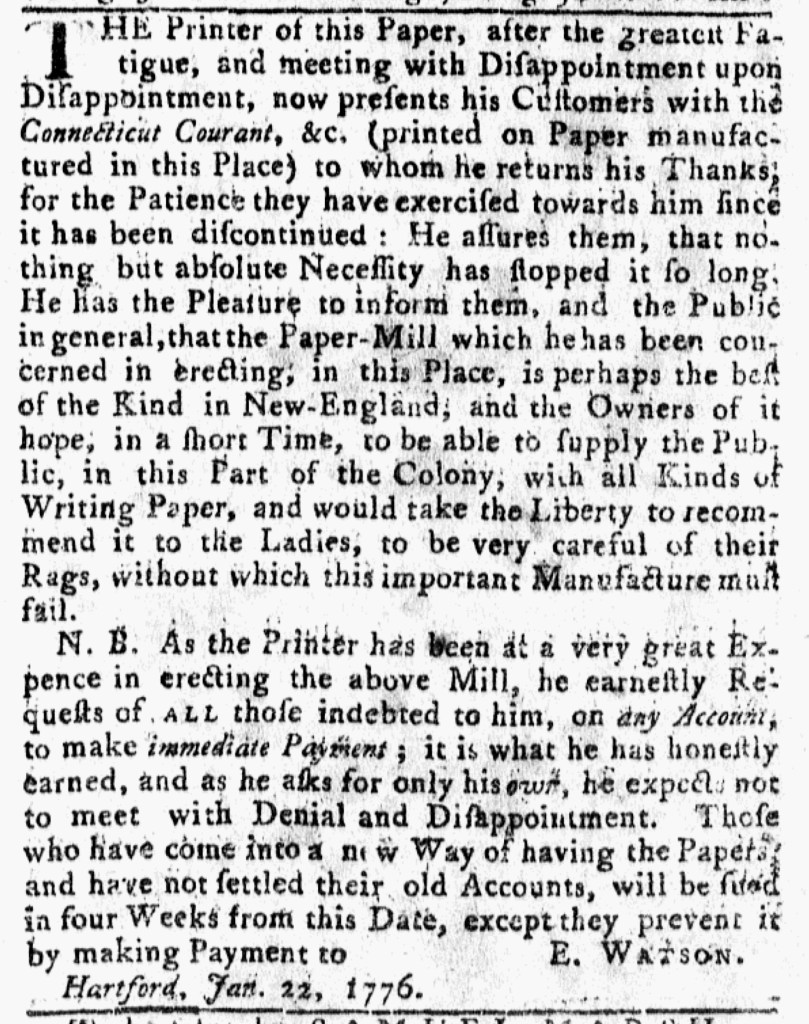

“The Paper-Mill which he has been concerned in erecting … is perhaps the best of the Kind in New-England.”

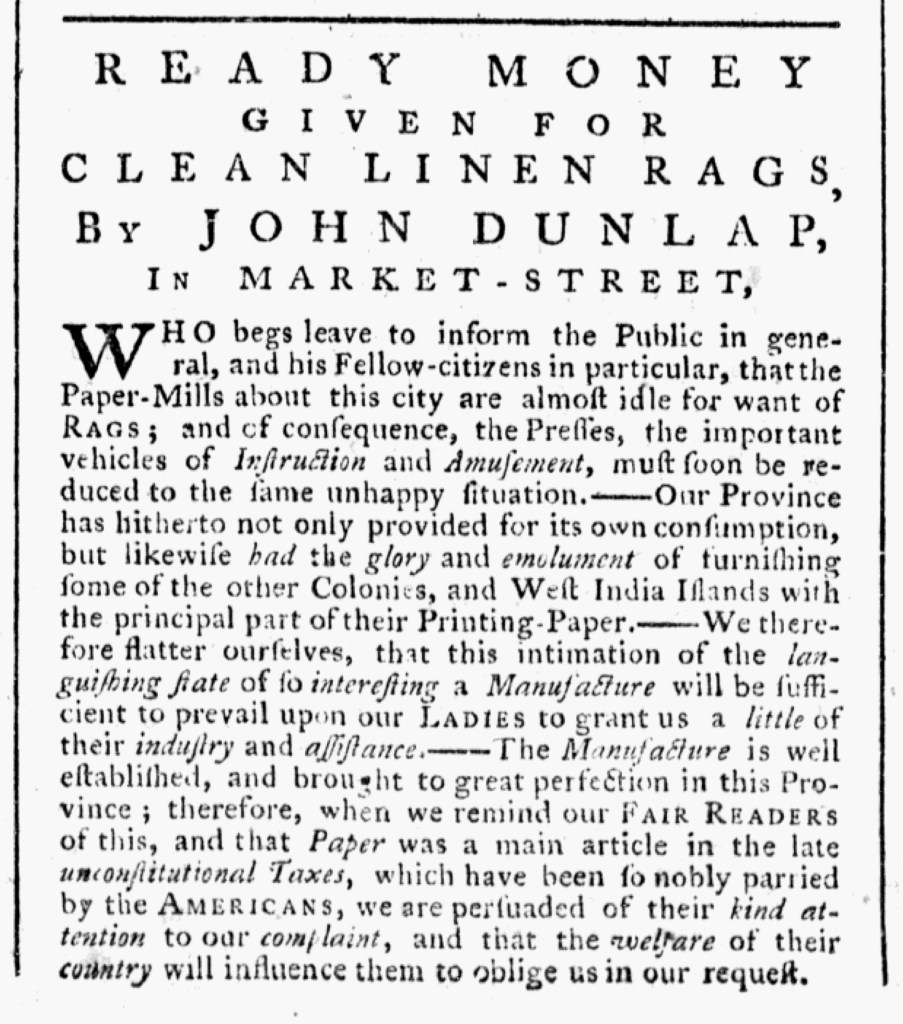

Ebenezer Watson, the printer of the Connecticut Courant and Hartford Weekly Intelligencer, briefly suspended publication of that newspaper due to a lack of paper in late December 1775 and early January 1776. The issue for December 11, “NUMBER 572,” was the last for over a month. The next known issue had neither a date nor a number in the masthead, but the news from Hartford on the final page bore the date January 15. The issue for January 22, “NUMB. 574,” had both a date and number in the masthead. A handwritten note at the bottom of the first page of the December 11 edition digitized for the America’s Historical Newspapers database states, “There appears to be an interruption of four weeks,” consistent with the issue numbering.

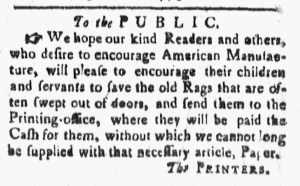

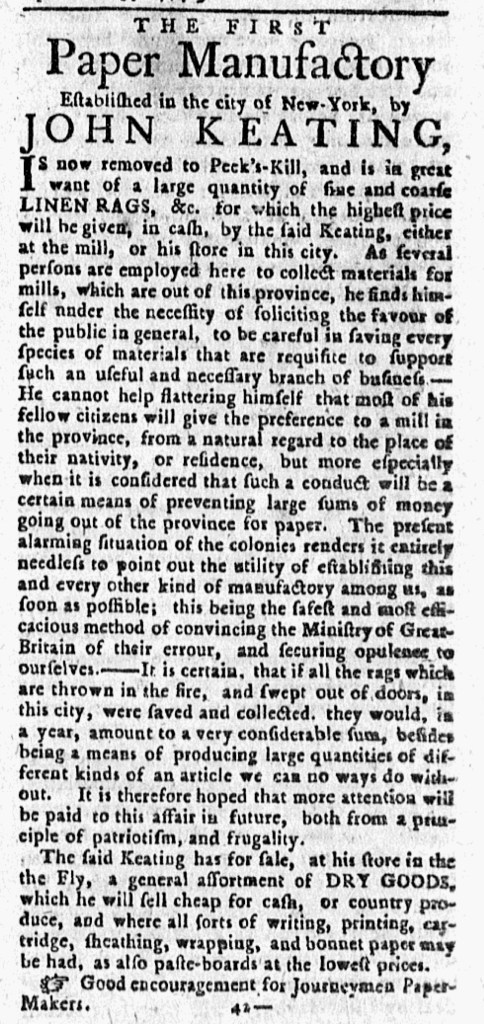

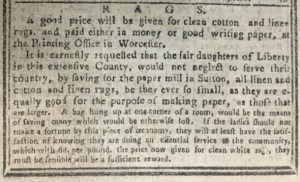

Watson inserted a notice about the suspension in the January 22 edition and the next two issues. “THE Printer of this Paper, after the greatest Fatigue, and meeting with Disappointment upon Disappointment,” he explained, “now presented his Customers with the Connecticut Courant, &c. (printed on Paper manufactured in this Place).” That made the Connecticut Courant yet another newspaper that experienced difficulties due to lack of paper during the first year of the Revolutionary War. Watson expressed appreciation “for the Patience [his subscribers] have exercised toward him since it has been discontinued” while simultaneously “assur[ing] them, that nothing but absolute Necessity has stopped is so long.” During the newspaper’s hiatus, Watson had been “concerned in erecting” a paper mill. Perhaps it produced the paper that allowed him to resume publishing the Connecticut Courant. He anticipated that “in a short Time” the mill, “perhaps the best of the Kind in New-England, would “be able to supply the Public, in this Part of the Colony, with all Kinds of Writing Paper.” For that to happen, he recruited the assistance of “the Ladies, to be very careful of their Rags without which this important Manufacture must fail.” In other words, the paper mill needed clean linen rags to recycle into paper to use in writing letters and publishing newspapers. In addition to rags, Watson needed to cover “the very great Expence in erecting the above Mill,” so he called on “ALL those indebted to him, on any Account, to make immediate Payment.” Watson aimed to continue disseminating news about the momentous events occurring in the colonies, but he needed the cooperation of both women saving rags and customers paying off accounts to make that possible.