What was advertised in a revolutionary American newspaper 250 years ago today?

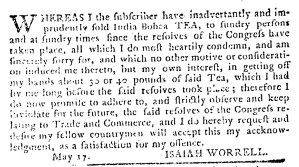

“I … have inadvertently and imprudently sold India Bohea TEA, to sundry persons and at sundry times.”

Isaac Worrell needed to do some damage control when others discovered that he had been selling tea in violation of the third article of the Continental Association in the spring of 1775. That nonimportation agreement, devised by the First Continental Congress the previous fall, stated “we will not purchase or use any Tea imported on Account of the East India Company, or any on which a Duty hath been or shall be paid; and, from and after the first Dat of March next, we will not purchase or use any East India Tea whatever.” Yet Worrell had not abided by those terms.

In an advertisement that first appeared in the May 17, 1775, edition of the Pennsylvania Journal and ran again the following week, Worrell confessed that he “imprudently sold India Bohea TEA, to sundry persons and at sundry times since the resolves of the Congress have taken place,” though he claimed that he had done so “inadvertently.” Readers may have been skeptical that a prohibited act that occurred repeatedly happened “inadvertently.” All the same, Worrell hoped that they would take note of his explanation for the infractions and accept his apology. He asserted that he had “no other motive or consideration … but my own interest, in getting off my hands about 30 or 40 pounds of said Tea.” He also contended that he acquired the tea “long before the said resolves took place,” hoping that would make his offense seem less serious. At least he had not actively ordered or received new shipments.

Worrell assured his community that he had reformed. “I do now promise to adhere to, and strictly observe and keep inviolate for the future,” he proclaimed, “the said resolves of the Congress relating to Trade and Commerce.” He hoped that would be sufficient that “my fellow countrymen will accept this my accknowledgment, as a satisfaction for my offence.” The Continental Association called for breaking off all ties, commercial and social, with those who violated it, yet Worrell hoped that his apology would outweigh his flimsy excuses to restore him to the good graces of the public. That he managed to sell “30 or 40 pounds of said Tea,” however, suggests that many others did not obey the terms of the Continental Association. Loyalists accused Patriots of cheating, especially when it came to tea. Worrell’s notice seems to support such allegations.