What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago this week?

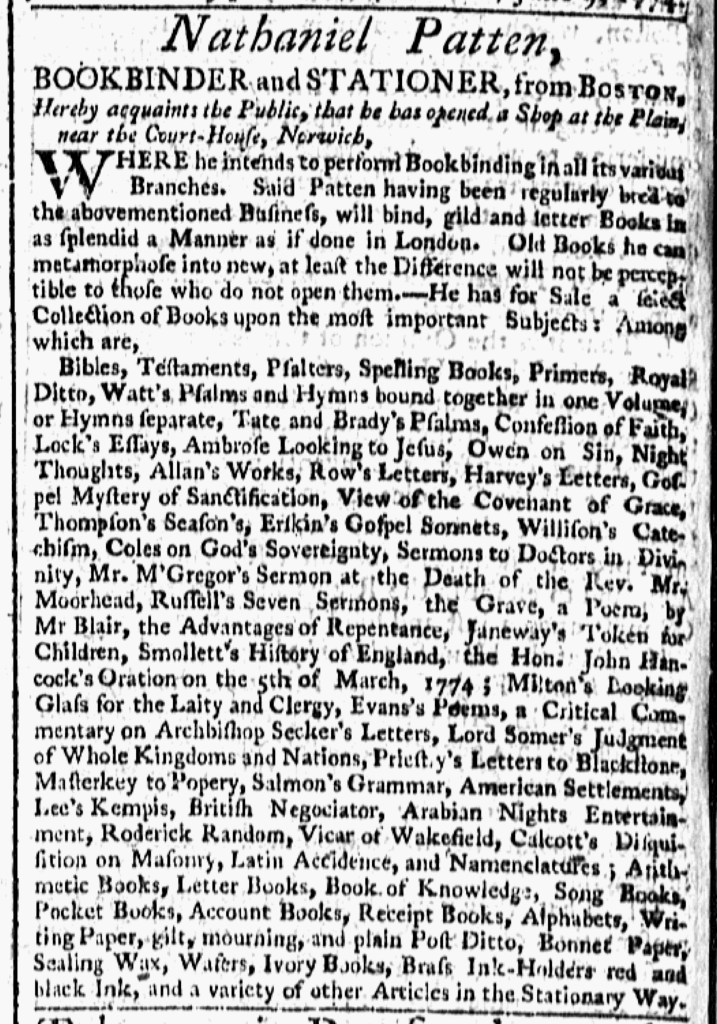

“NATHANIEL PATTEN, BOOK-BINDER & STATIONER.”

The decorative border that enclosed David Nevins’s advertisement for hats and hat trimmings in the Norwich Packethelped in distinguishing it from most others in that newspaper, yet it paled in comparison to the use of ornamental type in Nathaniel Patten’s advertisement. Patten, a bookbinder and stationer, commissioned a border for his notice, but he arranged for something much more elaborate than the relatively simple borders for Nevins’s notice and another placed by clock- and watchmaker Thomas Harland.

For some readers, the border for Patten’s advertisement may have evoked a highboy chest or other large piece of furniture. It may even have been intended as a bookcase and secretary desk that would have held the various books and stationery listed within the border. For the lower portion, the left, right, and bottom of the border were composed of a single line of decorative type, just like the borders in the other advertisements, while in the upper portion the left and right sides had three lines of even more intricate type. Those sides rose into an arch composed of other kinds of detailed printing ornaments. The compositor even created five finials, one each on the left and right at the bottom of the arch and three clustered together at the top. The year, 1774, appeared within a pendant inside the arch, much like a piece of furniture would have an engraving. If the type remained set into the new year, Patten had the option to update the date. The advertisement was massive, filling almost an entire column on the final page of the November 17, 1774, edition. The first time that it appeared, it ran on the first page on November 3, that time occupying an entire column because of the amount of space required for the masthead. The border appeared heavy, giving Patten’s advertisement more weight compared to others in the Norwich Packet. The finished product does not reveal how closely Patten worked with the compositor in designing or approving the border. Whatever the case, he almost certainly paid extra for it.

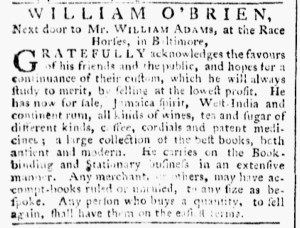

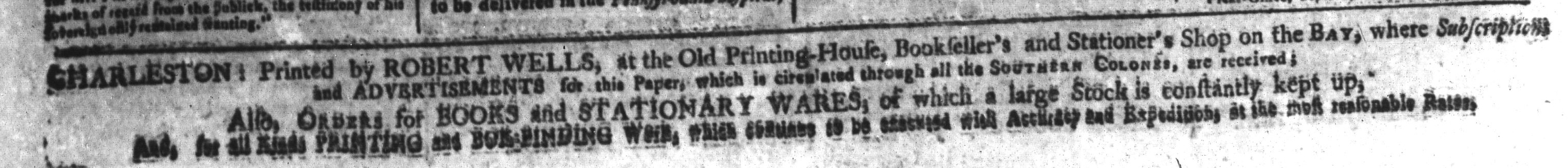

That newspaper had recently marked its first year of publication. Throughout that time, it did not tend to incorporate visual images except for the packet ship that appeared in the masthead. The printers did not make stock images of ships, houses, horses, indentured servants, or enslaved people available to advertisers, nor did advertisers commission woodcuts that represented their businesses. However, the newspaper did regularly embellish advertisements with decorative borders, establishing a different kind of visual appeal to engage readers.