What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

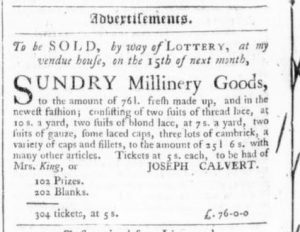

“To be SOLD, by way of LOTTERY … SUNDRY Millinery Goods.”

Joseph Calvert operated a vendue (or auction) house, where he likely sold some of his own wares but also earned commissions for assisting other entrepreneurs to sell their merchandise. The latter appears to have been the case in this instance, considering that the advertisement directed potential customers interested in “SUNDRY Millinery Goods” to see “Mrs. King.” The advertisement listed a variety of goods, many of them certainly imported. Yet describing the “Millinery Goods” as “fresh made up, and in the newest fashion” suggested that King was not merely a shopkeeper who sold goods that arrived readymade. She likely also worked as a milliner herself, making or modifying “a variety of caps and fillets … with many other articles.”

The vendue master and the milliner advertised a scheme designed to liquidate King’s merchandise and guarantee revenues of £76. Rather than hold an auction that might yield lower bids, they instead sponsored a lottery. King’s inventory would be divided into 102 lots to be distributed as prizes for winners. Only 304 tickets were to be sold, thus guaranteeing participants that each ticket had approximately a one-in-three chance of winning a prize (rather than being one of the “Blanks”). Presumably, the merchandise had been divided into lots of varying values with certain prizes much more significant windfalls for winners than others.

Colonists regularly bought and sold goods by vendue in the eighteenth century. Auctions were often forms of entertainment, but Calvert and King introduced an additional layer of excitement and anticipation in their attempt to incite interest in the “SUNDRY Millinery Goods.” Selling these items “by way of LOTTERY” may have attracted buyers willing to gamble on huge rewards for a modest investment, buyers that may not have been interested or able to participate in bidding at a traditional auction.