What was advertised in a colonial American newspaper 250 years ago today?

“BOHEA, GREEN, and HYSON TEA.”

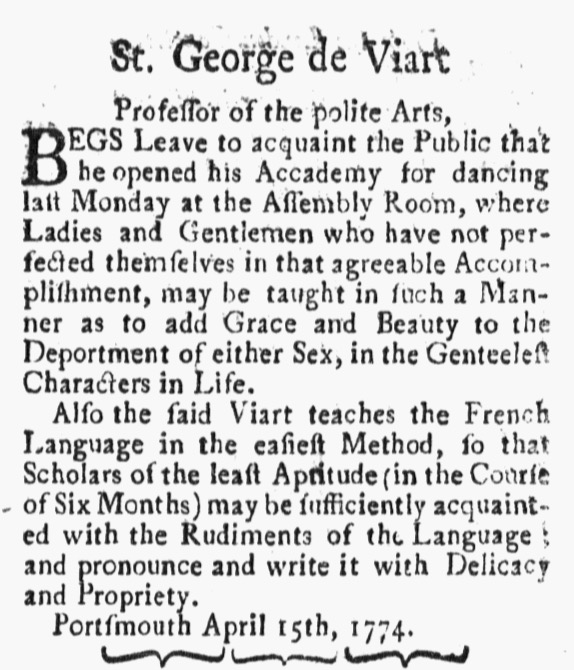

Not all colonizers dispensed with advertising, selling, and drinking tea as an immediate response to the Boston Tea Party, especially if the tea in question had not been subject to import duties. In April 1774, Pott Shaw advertised “BOHEA, GREEN, and HYSON TEA, warranted of the finest Quality,” in the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal. Shaw did not reveal when the tea arrived in the colony, by what means, or its origins, leaving those details to prospective customers to ask about, if they chose to do so, when they made their purchases. Buying and selling this particular commodity occurred in the context of conversations about the politics of tea.

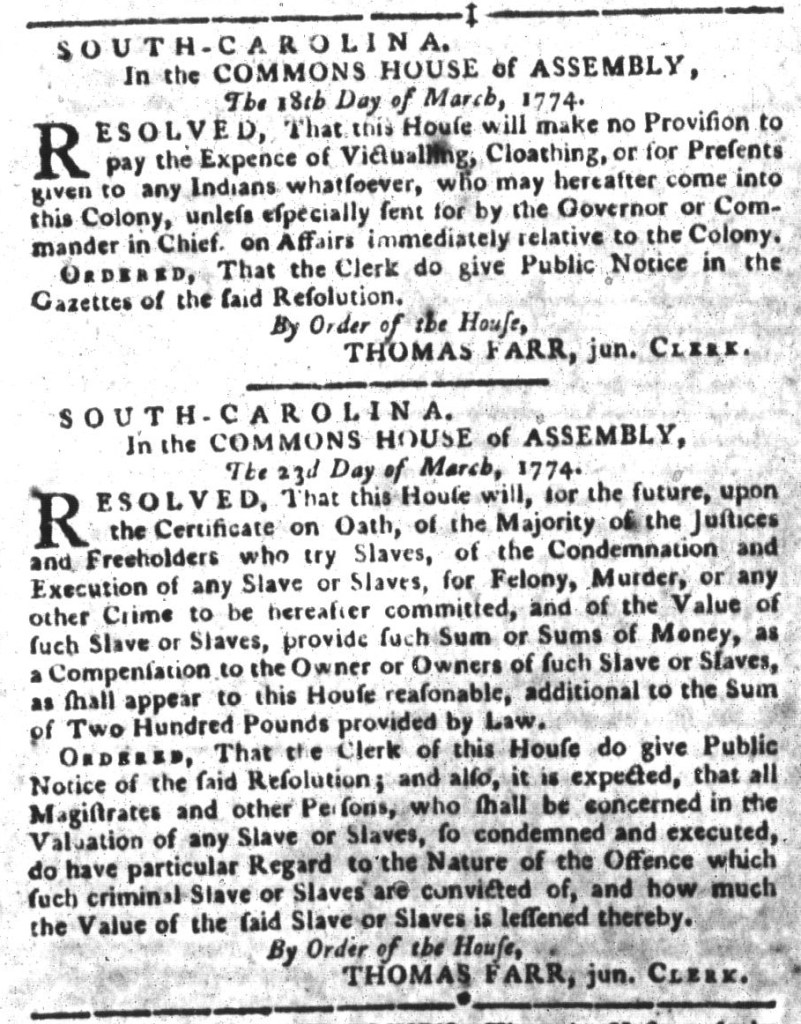

The April 19 edition of the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal carried some of the same updates about possible reactions to the Boston Tea Party that appeared in the Connecticut Courant a week earlier. Throughout the colonies, printers reprinted news from one newspaper to another. In this instance, both newspapers carried an “Extract of a letter from London, January 24,” that originally ran in newspapers in Philadelphia. It briefly stated, “Three men of war are ordered to be in readiness to sail for Boston, and exact payment for the TEA,” without providing additional information, including who had written the letter. Readers had to decide for themselves whether the report was accurate or merely rumor. Another news item, this one having arrived via New York, reported that the “intentions of the British administration, relative to the American duty on tea, are not yet fixed.” Readers in Charleston and Hartford read both these dispatches from London. They also encountered advertisements for tea in the same issues that carried that news.

Readers of the South-Carolina Gazette and Country Journal also read about commemorations of events that contributed to the imperial crisis. From Boston, they learned that “the horrid tragedy of the 5th of March,” the Boston Massacre, “was observed with the usual solemnity” on its fourth anniversary. That article described “a portrait of that inhuman and cruel massacre” put on display and the ringing of bells throughout the city for an entire hour. An update from New York followed, describing dinners that celebrated the “anniversary of the repeal of the STAMP-ACT.” Abuses perpetrated by both British soldiers and Parliament received attention alongside news about tea.

For the moment, however, that did not result in merchants, shopkeepers, and others refraining from advertising and selling tea in South Carolina or Connecticut or other colonies. The beverage was exceptionally popular, making it difficult to curtail consumption. Eventually, colonizers did enact boycotts, but some people still devised ways to evade them, at least according to Peter Oliver’s account. Although some entrepreneurs opted not to sell (or at least not to advertise) tea following the Boston Tea Party, it did not immediately disappear from shelves or newspaper advertisements.